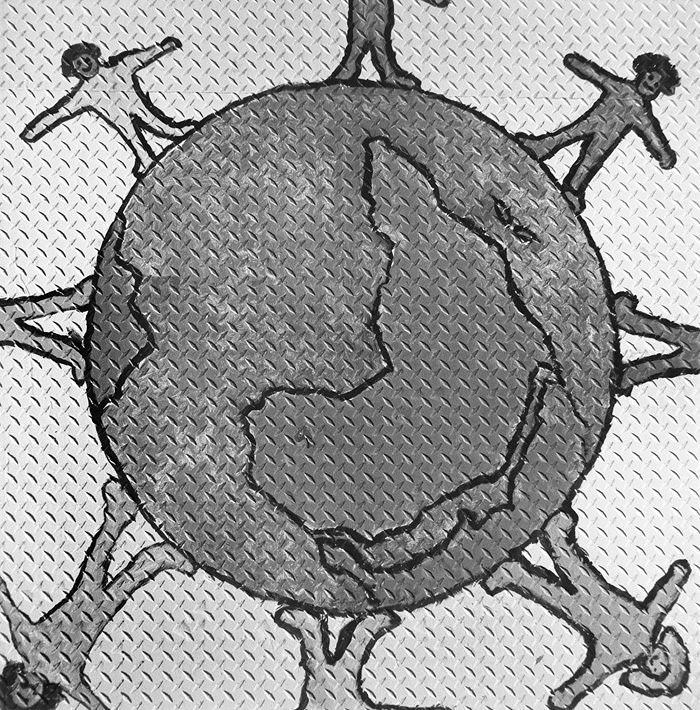

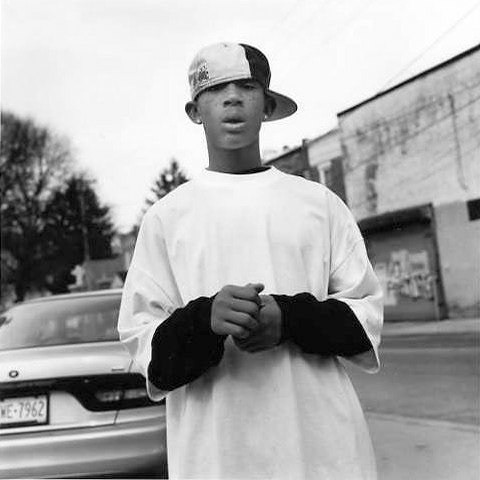

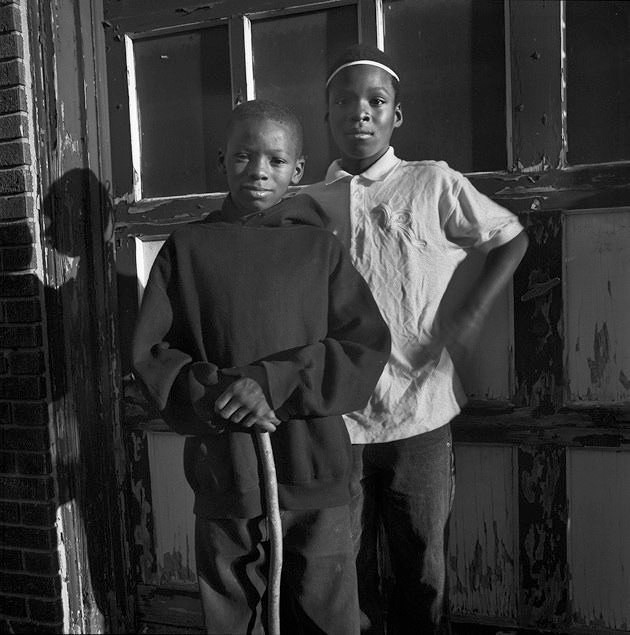

A Germantown Document (2002-2010) asks how the past and the present rise to legibility as aspects of one another, and how photographs prompt the imagination of history. The project examines a rich urban geography—Philadelphia’s Germantown—and the ways the neighborhood’s current actualities interrogate American ideals over time.

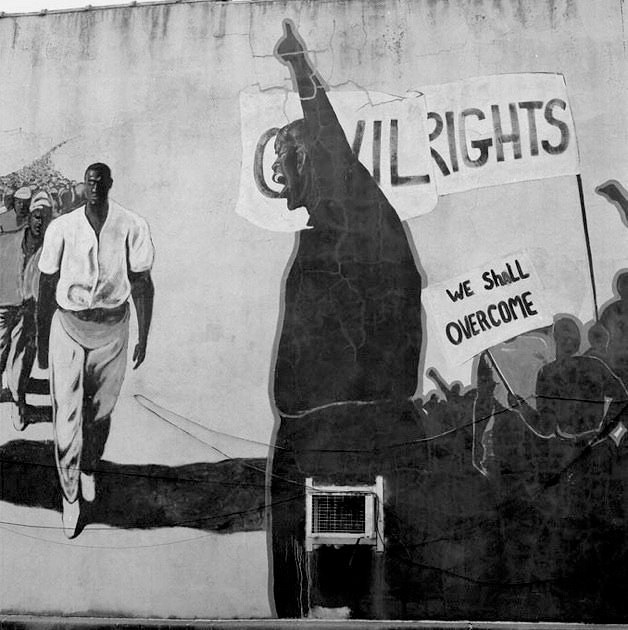

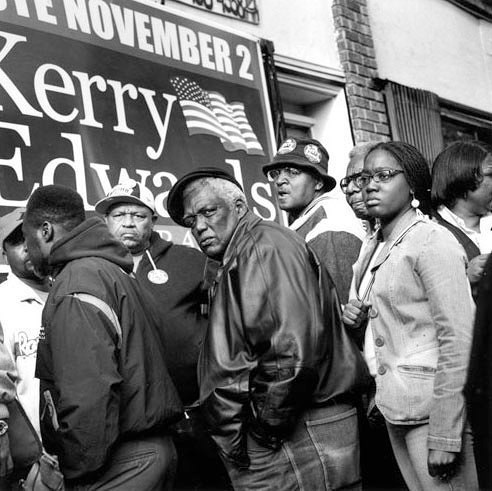

Founded more than 325 years ago by Quaker and Mennonite pietists, Germantown is in many ways a microcosm of the development of the American city. From its beginnings as a village upcountry from Philadelphia, it became a township, an outlying suburb of the city, an industrial center incorporated into the city, a bustling city district, and finally a struggling “inner city” neighborhood—and retains elements of all of these phases. Remarkably, Germantown has actively participated in the struggle to define and maintain American ideals from generation to generation. It was the site of the first public protest against slavery in North America (1688) and of an important battle in the Revolutionary War (1777), and served as the de-facto federal capital in the early years of the republic, when yellow fever plagued Philadelphia. In the antebellum period, it was a key center of anti-slavery activism and a major destination on the Underground Railroad. In the 20th century, it was a center of the suffrage movement, a locus of civil rights activism in the 1940s-60s, and of antiwar activism since World War I. At the turn of the twenty first century, it is a dense, sometimes bewildering patchwork of prosperity and poverty, of remarkable and partly ruined historical architecture, of co-habitant African American and white communities, and of durable middle class commitment to the city co-mingled with the economic challenges characteristic of urban America.

This project wrestles with the ways that Germantown separates and also unifies temporal shifts, by turns reflecting and deflecting core American ideals and civic challenges—and so forms a prism of historic irresolution. So doing, the project addresses several issues central to the understanding of the American experience over time.

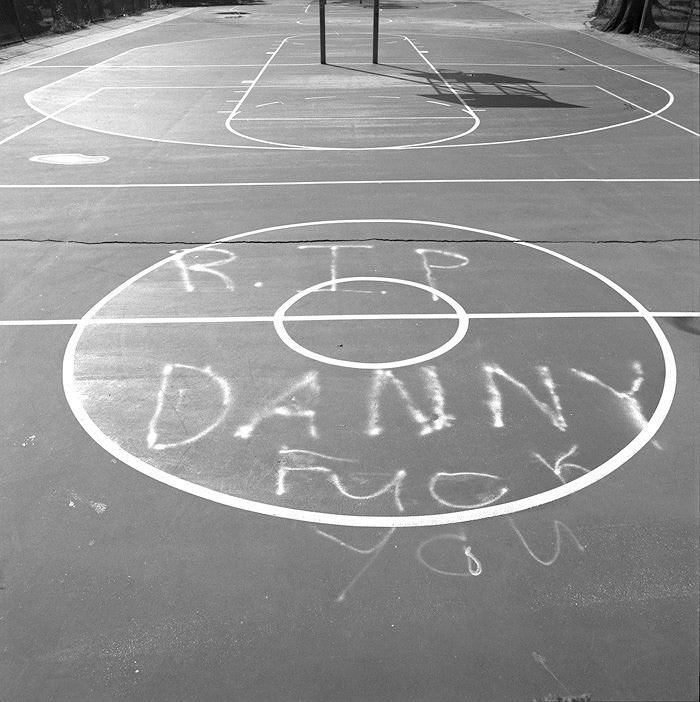

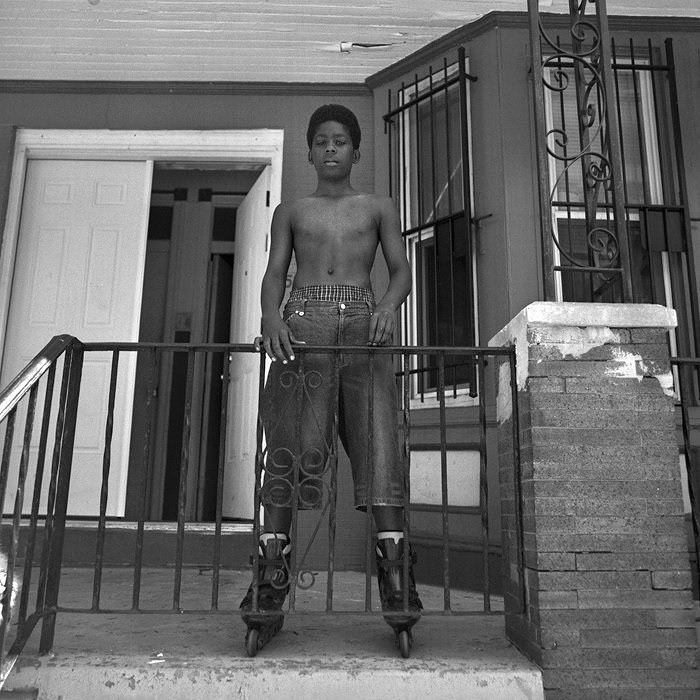

First, Germantown concentrates within itself the tensions between civic ideality—the American city as a place of democracy, enterprise and social growth—and its opposite, the city as a place of danger, a menace, a wasteland. My aim with this work is to refuse both nostalgia and elegy as adequate responses to these irreconcilables, and instead to test the neighborhood’s resiliences against its anomic realities, its promises against its bereftness. Second, the project asks about the legacy of Germantown’s religious and political activism, in which one finds the soul of the American experiment. How has the neighborhood’s long history of progressive politics inflected the American inner city as it arrived in Germantown in the second half of the 20th century? How does contemporary Germantown live up to the liberatory and irenic visions of earlier generations, if at all? Third, as a palimpsest of the American city over time, Germantown contains ruins, both physically and psychically. On the one hand, these ruins token collective memory, and on the other hand (precisely because of their connection to poverty and uneven development in the American context), they token devastation. Germantown’s ruins form a patrimony of their own—but how does a nation whose most cherished myths pivot on triumph and destiny handle a patrimony of loss?

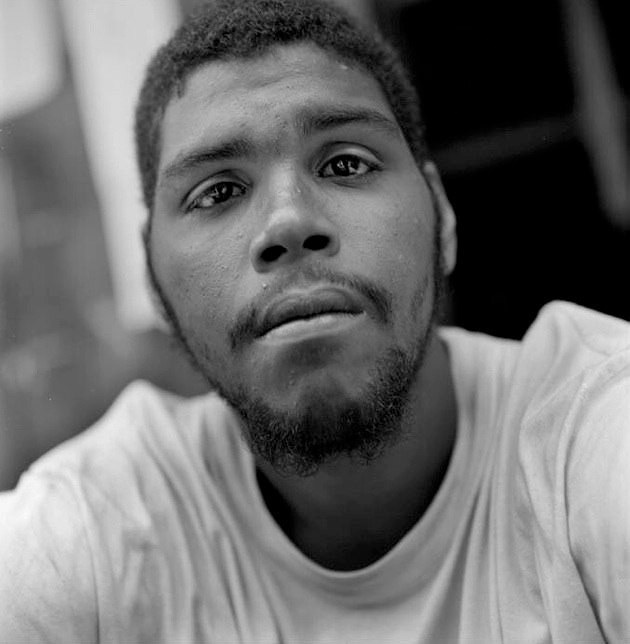

As I see it, the leading problems of documentary are well matched to the complexity of a place such as Germantown. These problems no longer pivot on the (familiar) debates between fact and style, revelation and personal vision. Rather they concern the witting use of the paradoxical quality of the photographic image—specific yet ambiguous, direct yet unstable—to do documentary work, in the case of Germantown to examine those forms of social history that are themselves (urgently) unstable and unresolved.

A key influence on this project is the work of Paul Strand, with whose ambitious books I have wrestled for several years, specifically Time in New England (1950). My project resumes work on certain of Strand’s problems (as it were), but with a less sanguine attitude toward American history and toward representational practices. Like Strand, I wish to use photographs to communicate what I understand as history’s actuality. And like Strand, my practice is rooted in exacting and unarrayed observation. In contrast to Strand’s effort to recapture American ideals using grave, essential form, the documentary strategy I am interested in—appropriate to my own generation, perhaps—is anti-essentialist. I do not approach history as an intact, wieldy object of shared experience so much as a fragile possibility for shared experience, constantly in need of illuminating (visual) questions.

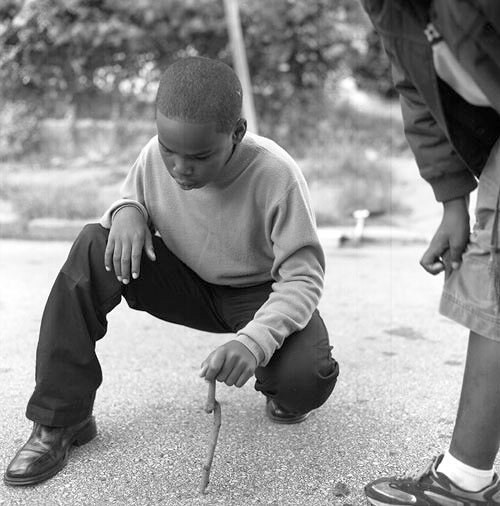

The pictures here, a small sample of my archive, lay out a set of visual contingencies, a frictive eventfulness of pictures—by turns empathic and reflective, proximate and distanced. They propose that a just image of Germantown is a matter of attempting a sustained image-situation in which pictures work on and against each other, one picture elaborating and then undoing the impact of another. In the movement between pictures—the pictures being prompts, goads, jumping-off points—Germantown’s history becomes implicated in the observable, if not recuperated in it.

Philadelphia, 2010