1. there were storms here yesterday unlike i have seen here before, gusts almost enough to blow a person down and surf tossing itself over the seawalls with shocking ease, as if to spit at the sea-edged city’s desire to protect itself, and the centuries of toil that made and maintained the barrier. the floors of the restaurants lining the harbor were washed all day by saltwater. my feet this morning are stained with the tannins of all-day-wet leather.

2. today, i went out beyond the city to look into the sea in its day-after calm. if yesterday it was next to impossible to find a place for myself in the storms, today i thought i might find a readier location for a human being between the motions of the two waters, salty from below in surges and fresh from above in eyelet drops. today perhaps i might find a dwelling in the sea's post-tempest repose?

3. i have a lot of gall even to presume to seek a “my” and an “own” and a “place” at all. where i put myself atop the seawall yesterday to photograph, and where i put myself in the mesmerism of the surf today, it feels as if i am poised to be touched by what i can only awkwardly call the source-current, the source-wind. so touched—if i am so lucky—my hours go by in a kind of trance, the tripod more of a prayerbook than the yom kippur machzor of two days ago, and the trance more entrancing than a day of fasting and reciting the truths of my failings and my gratitudes—which also touch infinity, if less palpably.

4. apparently the proto-indo-european root “ghieh-”—meaning “to yawn, to gape, to be wide open”—is the progenitor of a family of words that attempt to name the mystic opposite of order. the greek χάος, chaos, is the word to which hesiod turns in order to describe primeval emptiness, as if to liken a wide open wordless mouth to an abyssal wellspring. (and isn’t it true that the boredom that yields a yawn and the shock that can open the mouth not for speaking can both feel strangely eternal?)

5. and apparently, also, at least according to eliot weinberger, the ancient chinese character for wind was constructed from a pictograph of a sail plus a pictograph of a snake, or a crawling creature made seaworthy. and creeping seaworthiness catalyzed many other words. wind plus the character for sickness meant insane. wind plus purity meant sexual longing. wind plus rain meant hardship and wind plus glory meant elegance or talent. wind plus tide meant political unrest and wind plus group meant political opportunists. a wind-man was a poet, and wind-flow meant sophisticated in literature. wind-sorrow meant special excellence in literature.

6. hebrew names wind and breath with the same word, רוּחַ, “ruach,” and when we bless god as רוּחַ הָעוֹלָם, “ruach ha-olam,” this in the differentiation that english requires yields “breath of the world” or “wind of the universe” or other such combinations—and i cannot help but remember a midrash, though i no longer remember where i heard it, that יהוה, the unpronounceable name of god, whatever else it means, is a way of writing the sound of wind, or the sound of our own breathing. on the seawall of chania in crete in yesterday’s storms, the sound of the wind was furious, perhaps some small indication of what the breath of god might sound like, as it were. me, in that sound i did not hear proto-indo-european or greek or chinese or hebrew or english, and i could not hear my own breath. but where wind overtook breath in sound, my own breathing continued quietly.

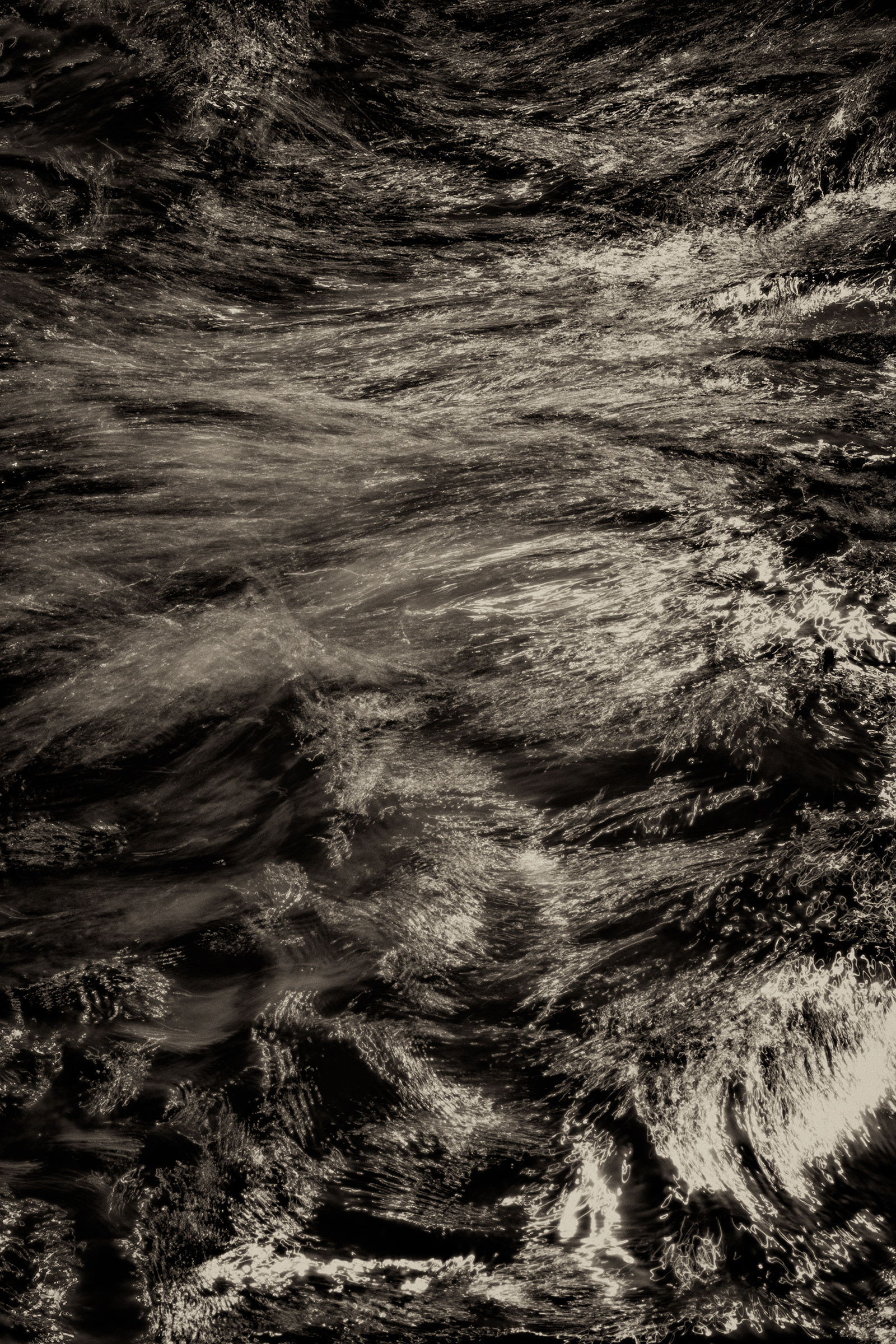

7. if wind draws musicians for obvious sonic reasons—i forgot to mention that weinberger says that in ancient chinese, wind also meant song—i suspect that wind draws a visual artist precisely because wind is not something that can itself be seen. its effects on the sea and the clouds and on stones can be seen, and these effects seem to point to some unfathomable origin, some place of sheer forcefulness, which is the deeper thing of longing and fascination. the truth is that i have been photographing at the ocean everyday for weeks now, and yesterday’s storm seemed to me almost a gift. i cannot entirely explain myself, except to say that i am trying to make an unfinished photograph, by which i mean an unfinishable image, an image that emulsifies its own finishedness. i want to make an image that returns its formedness to a greater unformedness. (i understand that this desire is entirely quixotic, and perhaps i have at last begun to make progress in forgiving my quixotic nature, which seeks most of all to unprotect the heart’s tenderness.)

8. jewish mysticism speaks of a nexus between being, יֵשׁ, “yesh,” and nothingness, אַיִן, “ayin,” with the postulation that god created—creates—existence from a (paradoxically) pre-existent non-existence, that-which-is from a vaster and perhaps simpler that-which-is-not. yesh, one might say, is being that has these properties: it begins and ends, it has stillness and motion, it is somewhere and not nowhere, it is visible and not visible, it is audible and not audible, it is palpable and impalpable, and so on. ayin, because it is apart from existence, cannot be described in any such declamatory terms: it neither begins nor ends, neither has nor lacks stillness and motion, neither has location nor lacks it, is neither visible nor invisible, is neither audible nor inaudible, is neither palpable nor impalpable, etc. god, as the source of yesh and ayin both, is unlike either of them. for the mystics, god cannot be rendered—not in words or in any way—but only referred to, for example as “without end,” אֵין סוֹף, “eyn sof.” rabbi lawrence kushner makes the connection between jewish speculative theology and the sea this way: “everything in the world,” he notes, “is the wave of which the eyn sof, or god, is the ocean. and our knowledge of the ocean is largely based on the way it manifests itself in the waves, that is, the yesh.”

9. to make an unfinishable image, it seems to me the key task is to separate what we can see from what we can say, to cleave form and name, in effect to disrupt recognition for the sake—perhaps!—of unexpected cognition. so i decided to give away much of what i could otherwise control, to create a photographic situation in which time itself would be the agent of the undoing. (it is one thing to act in time, to see an opportunity and take it, and another thing to let time act.) my exposures lasted a minute, which i suppose i could liken to אֶחָד, “echad,” or to oneness, though i am more inclined to find echad in the integrity of a clockless moment —call it the zero within the one—than the “unity” of a single measured minute.

10. i keep losing my way in the wind and surf, and perhaps it is this very losing that i should call poetry, in my case of the visual kind. i did not manage to make a photograph that unfinishes its own image, or that delivers form to the nothing. and chania today? it is still standing in its pauseless brush with the sources, current and wind—or perhaps a drop of god’s watery arrival.

10 + 0. to photograph not for the sake of pictures but for the images within them, and, then, to unhold the images for the sake of the emptiness they shelter within themselves—emptiness that is generative, fertile, and wild—is there a better word for all of this than “love?” is there a better word than love for the currents that move the wind and the water around the sensuous sphere that we call the earth? is there a better word for the boundless no-thing that moves the currents of the sensing mind and the senseful heart? and if a person is lucky enough in life to know them, is love is not what makes the muses themselves? is love not the very thing they circle, circulate, spin, round, wheel, wreathe as the city’s own sea-edge?

Chania / Paris, 2022-2024