In February, 2013, my friend Patrick Blanchfield invited me to accompany him to a gun show in south Atlanta. I'd never been to one, and following from my ongoing project on the murder epidemic in Philadelphia, These are the Names, I agreed to go. On a Sunday afternoon, we spent several hours looking at guns and the trade in guns, and listening to the stories of sellers and customers. I openly and unassumingly photographed.

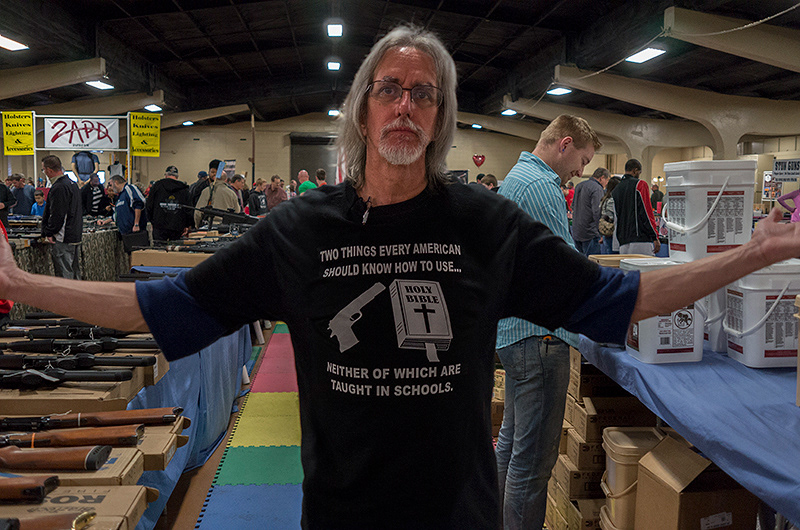

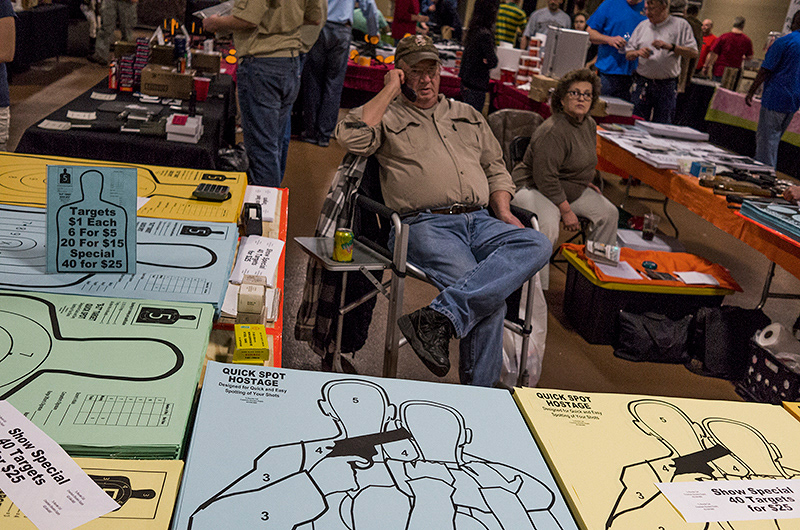

Though I tried to prepare myself in advance, it was admittedly shocking to me to see a cavernous hall (a wholesale produce market on weekdays) converted into an open market for lethal weapons, hundreds upon hundreds of them laid out on tables. Unlike "professional" trade shows, this was basically a gun flea market, with about half the vendors comprised of dealers, and half private sellers. Business was brisk. Per federal law, the show involved two registers of commerce: gun sales with background checks, conducted by the established dealers, and gun sales without background checks, conducted by "private sellers" and established dealers who can also choose to operate as private sellers. In addition to vendors with tables, many individuals walked the aisles brandishing their wares to potential customers. I was told by several people that this particular show has been very active, happening every weekend since the massacre at Newtown, Connecticut, as compared to every six weeks previously. Prices for most items were three to four times what they were before, owing to high demand following Obama's gun control initiative.

Patrick and I met many people, and had long conversations with a few. I was drawn especially to those there to sell things other than guns. One was a Cherokee family selling home-made "surivival kits" (medical supplies and bibles) to supplement the husband's modest income as a paramedic. We spoke at length with a woman who became an avid shooter only months previously, thirty years after her father, a Vietnam vet, committed suicide in a losing struggle with PTSD. She now sells home-made jewellery made with the spent shell casings she saves from her time at the shooting range. I met two Jewish doctors, one an anesthesiologist who calls herself "Dr. No-Pain," the other the son of Auschwitz survivors, who spoke at length about the Holocaust as the backbone of his ardent belief in unrestricted Second-Amendment rights.

Though I tried to prepare myself in advance, it was admittedly shocking to me to see a cavernous hall (a wholesale produce market on weekdays) converted into an open market for lethal weapons, hundreds upon hundreds of them laid out on tables. Unlike "professional" trade shows, this was basically a gun flea market, with about half the vendors comprised of dealers, and half private sellers. Business was brisk. Per federal law, the show involved two registers of commerce: gun sales with background checks, conducted by the established dealers, and gun sales without background checks, conducted by "private sellers" and established dealers who can also choose to operate as private sellers. In addition to vendors with tables, many individuals walked the aisles brandishing their wares to potential customers. I was told by several people that this particular show has been very active, happening every weekend since the massacre at Newtown, Connecticut, as compared to every six weeks previously. Prices for most items were three to four times what they were before, owing to high demand following Obama's gun control initiative.

Patrick and I met many people, and had long conversations with a few. I was drawn especially to those there to sell things other than guns. One was a Cherokee family selling home-made "surivival kits" (medical supplies and bibles) to supplement the husband's modest income as a paramedic. We spoke at length with a woman who became an avid shooter only months previously, thirty years after her father, a Vietnam vet, committed suicide in a losing struggle with PTSD. She now sells home-made jewellery made with the spent shell casings she saves from her time at the shooting range. I met two Jewish doctors, one an anesthesiologist who calls herself "Dr. No-Pain," the other the son of Auschwitz survivors, who spoke at length about the Holocaust as the backbone of his ardent belief in unrestricted Second-Amendment rights.

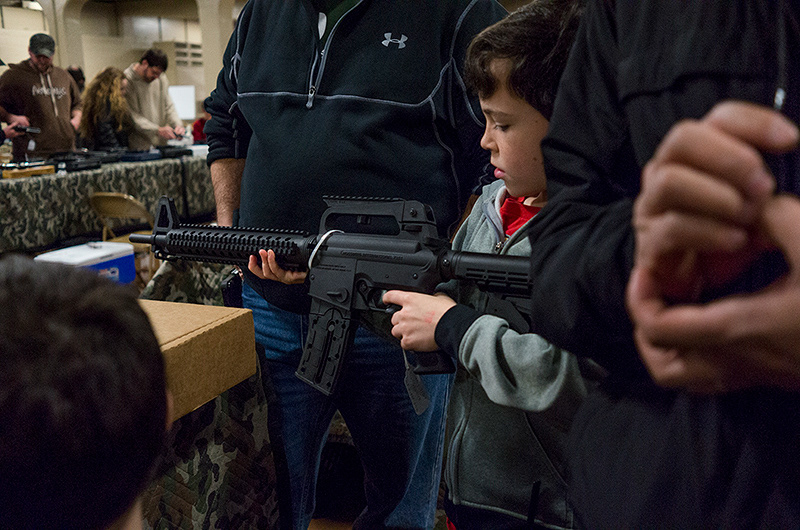

On April 24, 2013, the Daily Beast published a selection of my photographs––omitting those showing children at the gun show––together with an excellent reportage by Patrick Blanchfield: Art and Armor--Piercing Rounds.