The photographs here describe some of my stopping points in a journey into inner America. I do not mean a search for essences, but an encounter with the civilizational unconscious I know from birth. From birth: the ideals and obscenities of America were planted in my own unconscious, I who was born and raised in California and have since lived in many parts of the U.S. (and spent long periods away). A journey into inner America is, for me, ineluctably also a journey into the self.

Setting forth a visual journey into inner America, and its self in myself, I can only proceed by inference. Inner America is to be discerned, not beheld. It is to be felt, not witnessed. It exists as a drift in time and as an urgency within that drift. It exists in the places beside places, in place-adjacencies, in the margins and not quite out of sight, just next to objects of wanting and knowing. Inner America is not something visible and also not invisible. Why such paradox? I venture: because inner America, after all, roves and flees at will, itself scrambles after destiny and refuses fate, claims the earth and the spirit of the occupied continent with a heedless abandon and a will to innocence. (And I venture: there is a space between innocence and the loss of innocence, and inner America often dwells just there—in the dangerous realm of ersatz or false innocence, jealously guarded.) For a photographer, seeking inner America means traveling a narrow path set within the wide road, or to use a different metaphor—seeking out the charge, the electric difference between the image and the subject of that image. Or maybe I should say it plainly: inner America blushes near as a state of language, especially in the intervals between prepositions, as in the difference between “looking at” and “looking past” the surfaces, or between “I am from this country” and “I am of this country.” A state of language: not the sort of language suited to telling things, rather to showing them.

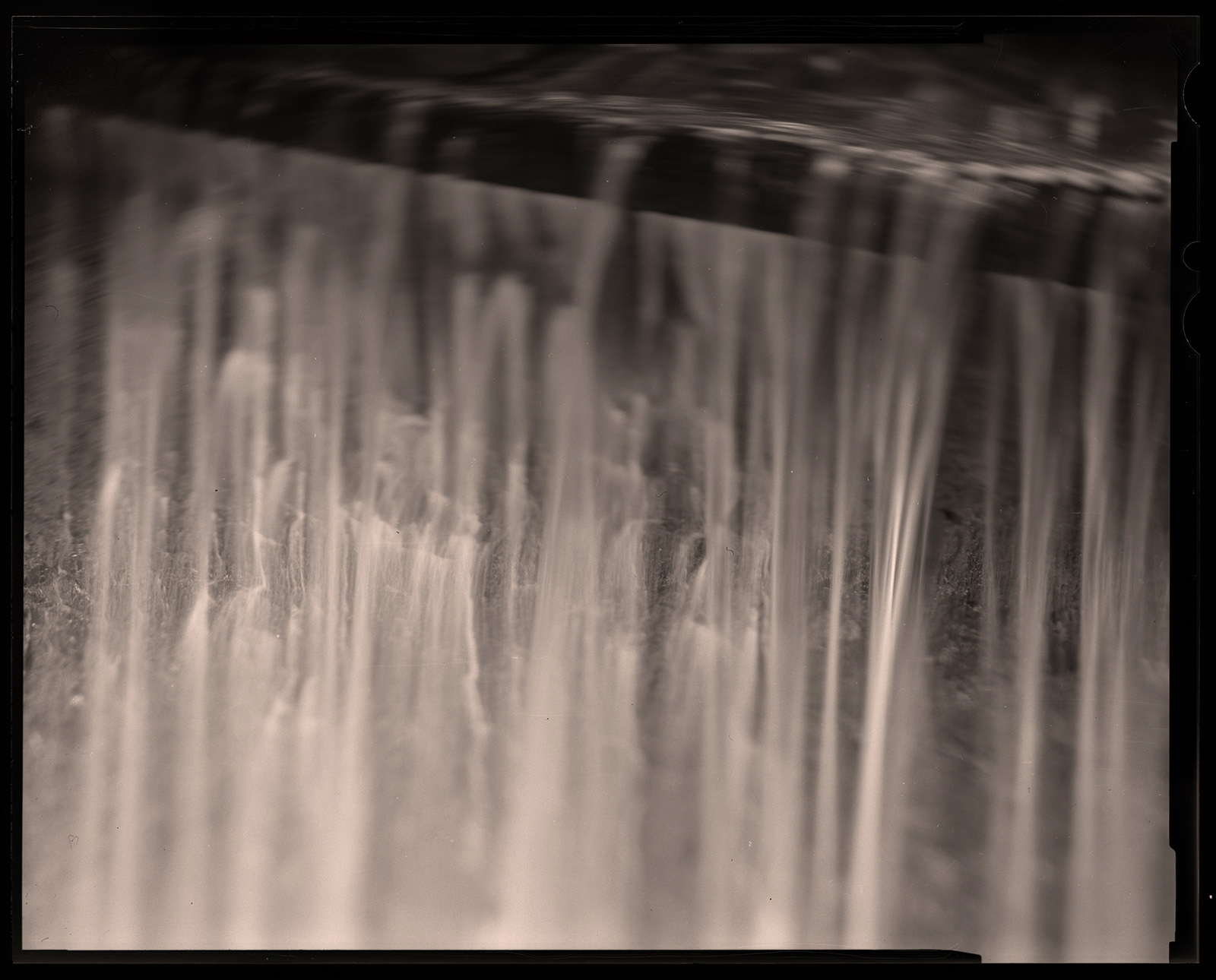

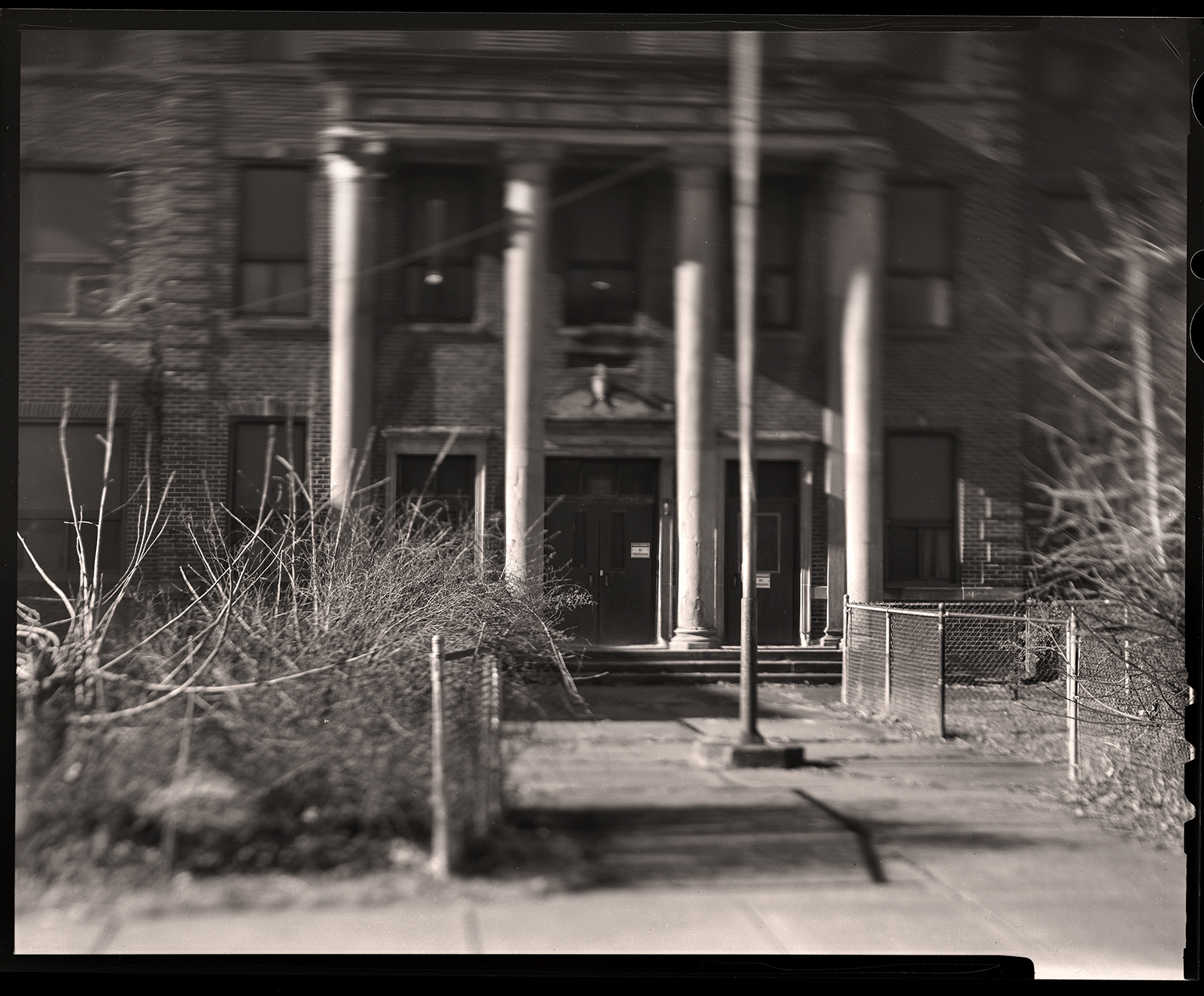

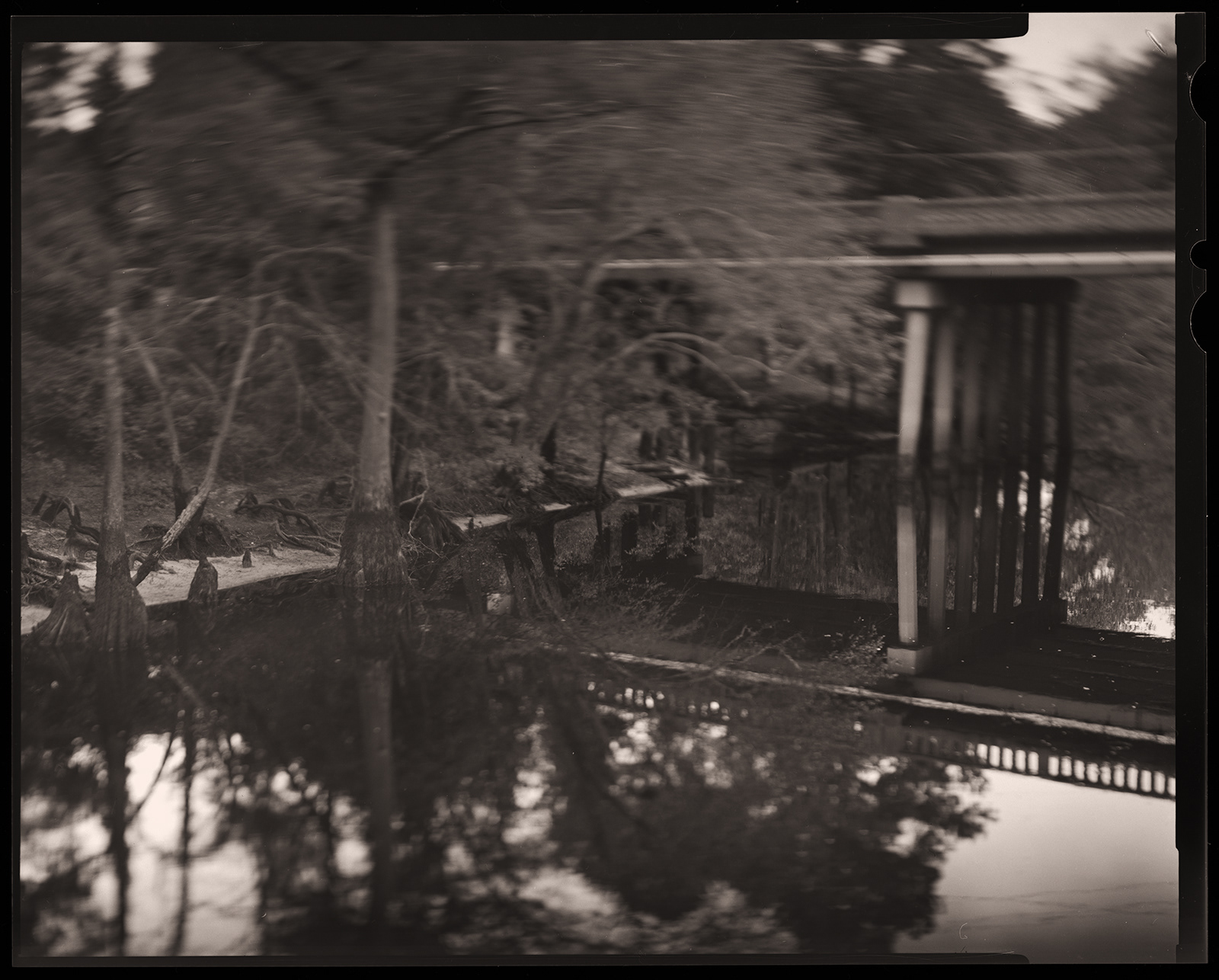

The following sequence is the first iteration of my search, my effort to bend the unconscious of America into the condition of images—the unconscious of America and, as I say, the self-unknowingness of the American self of me. The sequence is of two sources, braided together. One source is my own camera, a nineteenth century-style view camera. The camera is a remarkable tool of investigation and sometimes revelation, allowing the creation of specific focal corridors running at virtually any angle in space. The antique lenses I use with it have a distinct character, particularly with wide apertures, even more so when the lenses are tilted and shifted at wide apertures, and emphatically so at the edges the image circles, which I liken to event horizons. The view camera is a slow-working, contemplative tool, and rewards a slow-working, contemplative approach to the images it yields. I have studied its ground glass through and across perhaps fifteen thousand miles in the United States between 2015 and 2020. But the story is deeper. The aesthetics of these pictures took me a long time to work out—and I worked them out not in the U.S., rather in eastern Europe, where this approach was a method of grappling with the legacies of the Holocaust and its cultural unconscious, which suffuses the Jewish self of me. In the eastern European killing fields, the pictorial give and take between clarity and unclarity, resolution and irresolution reflected—for me—a conceptual give and take between comprehension and incomprehension, memory and forgetting. At a certain point, it occurred to me that I should see what would happen if I used these particular aesthetics to photograph in the U.S., where the historical trauma is different. And so I set out to try.

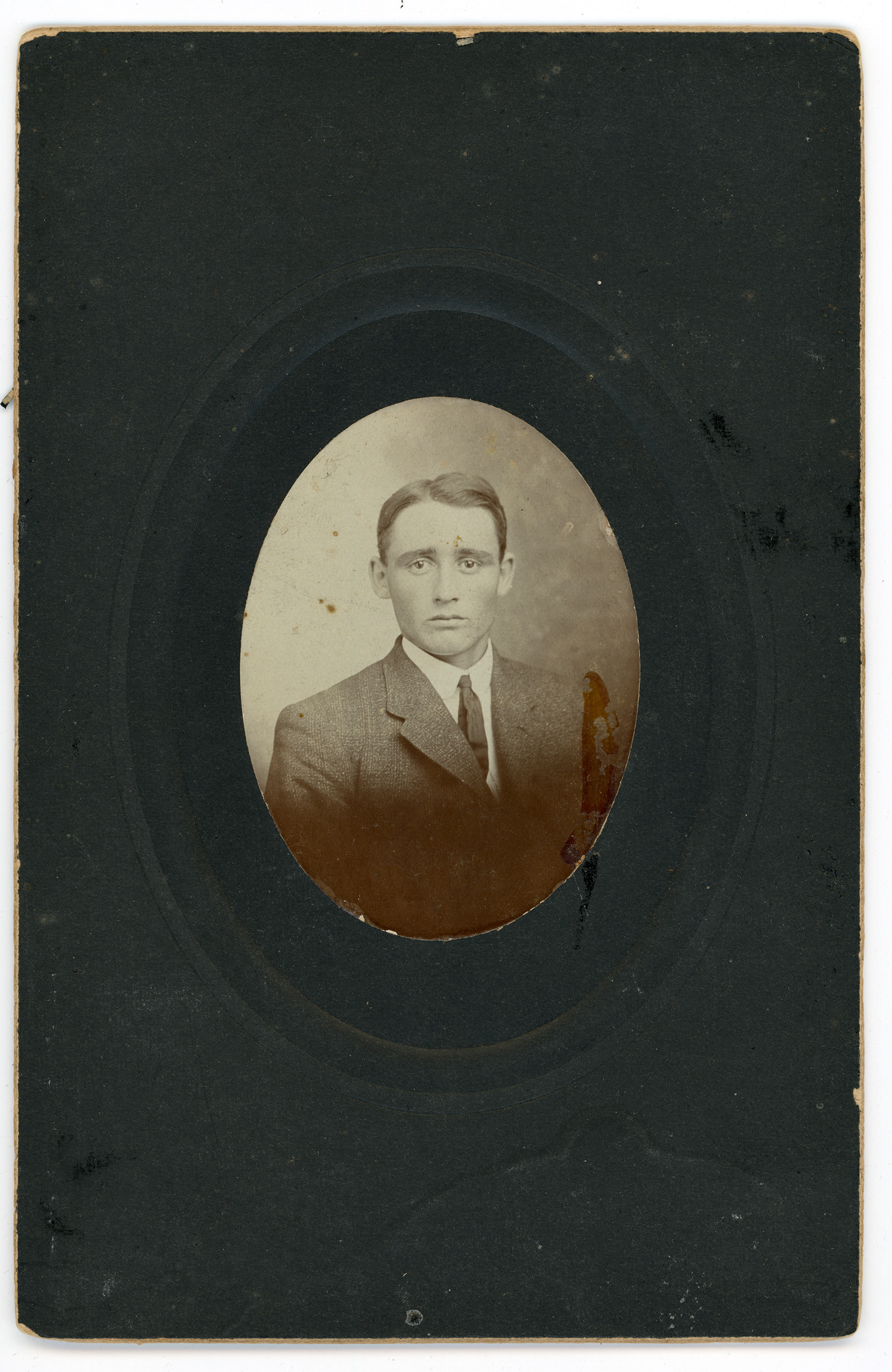

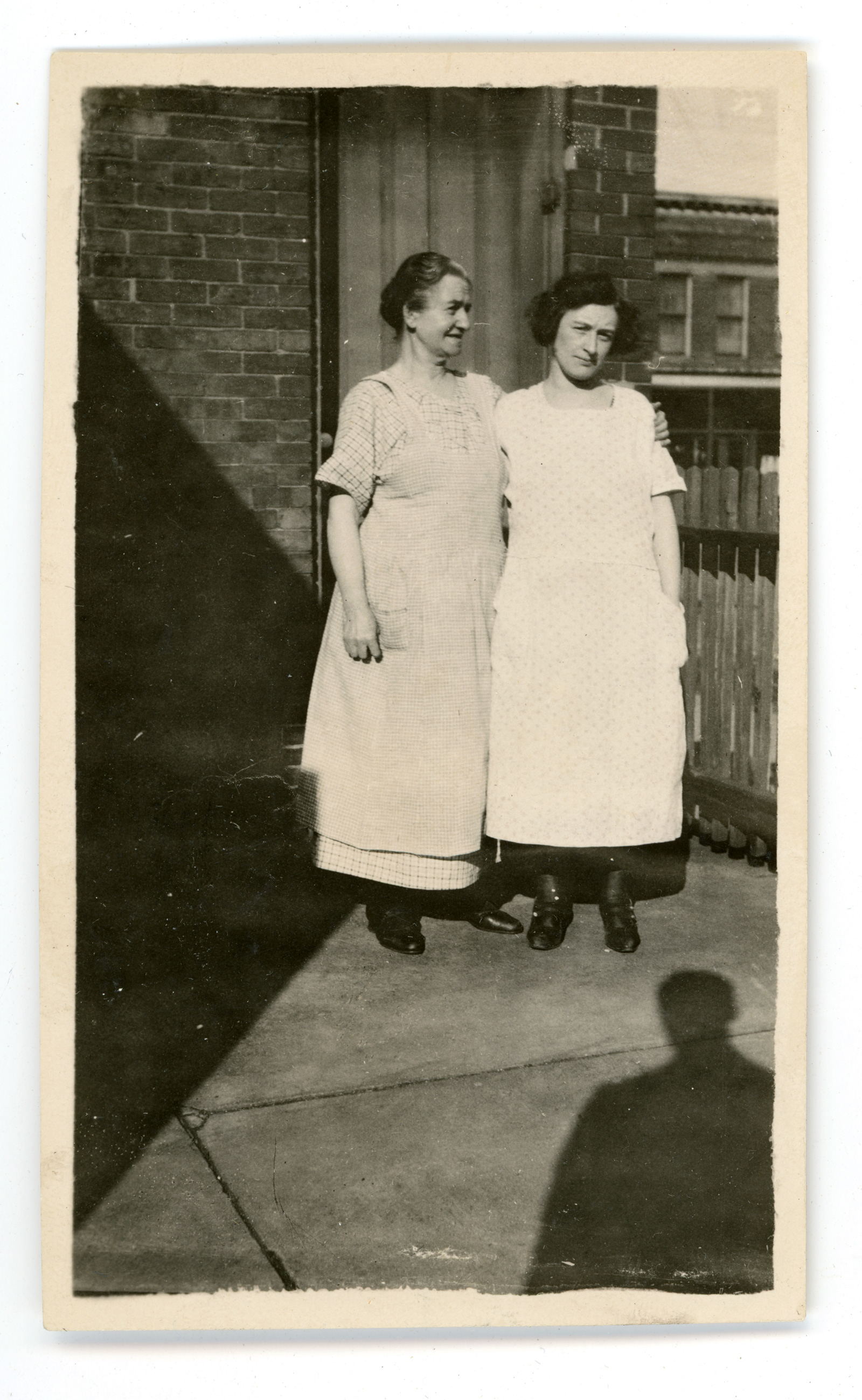

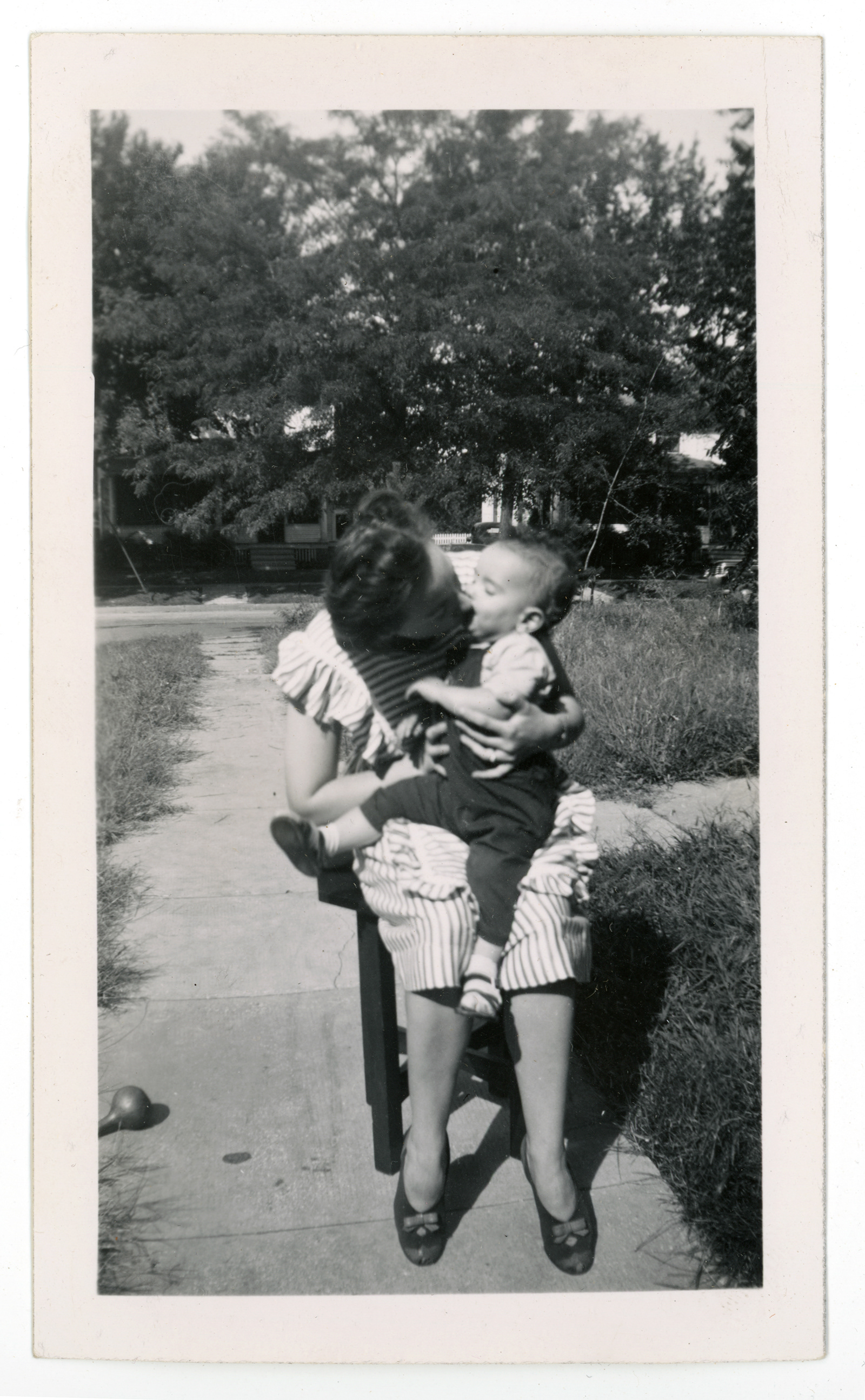

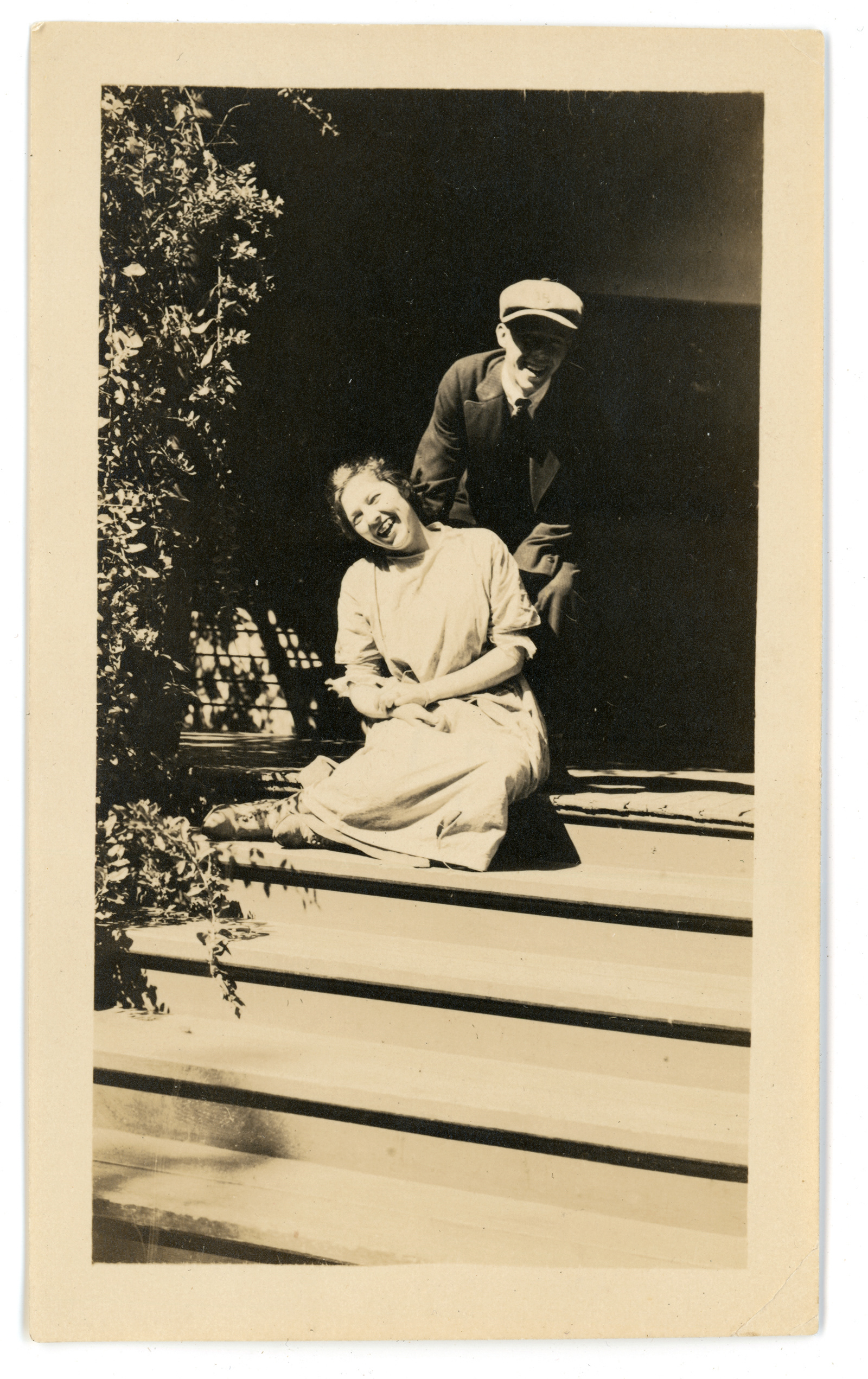

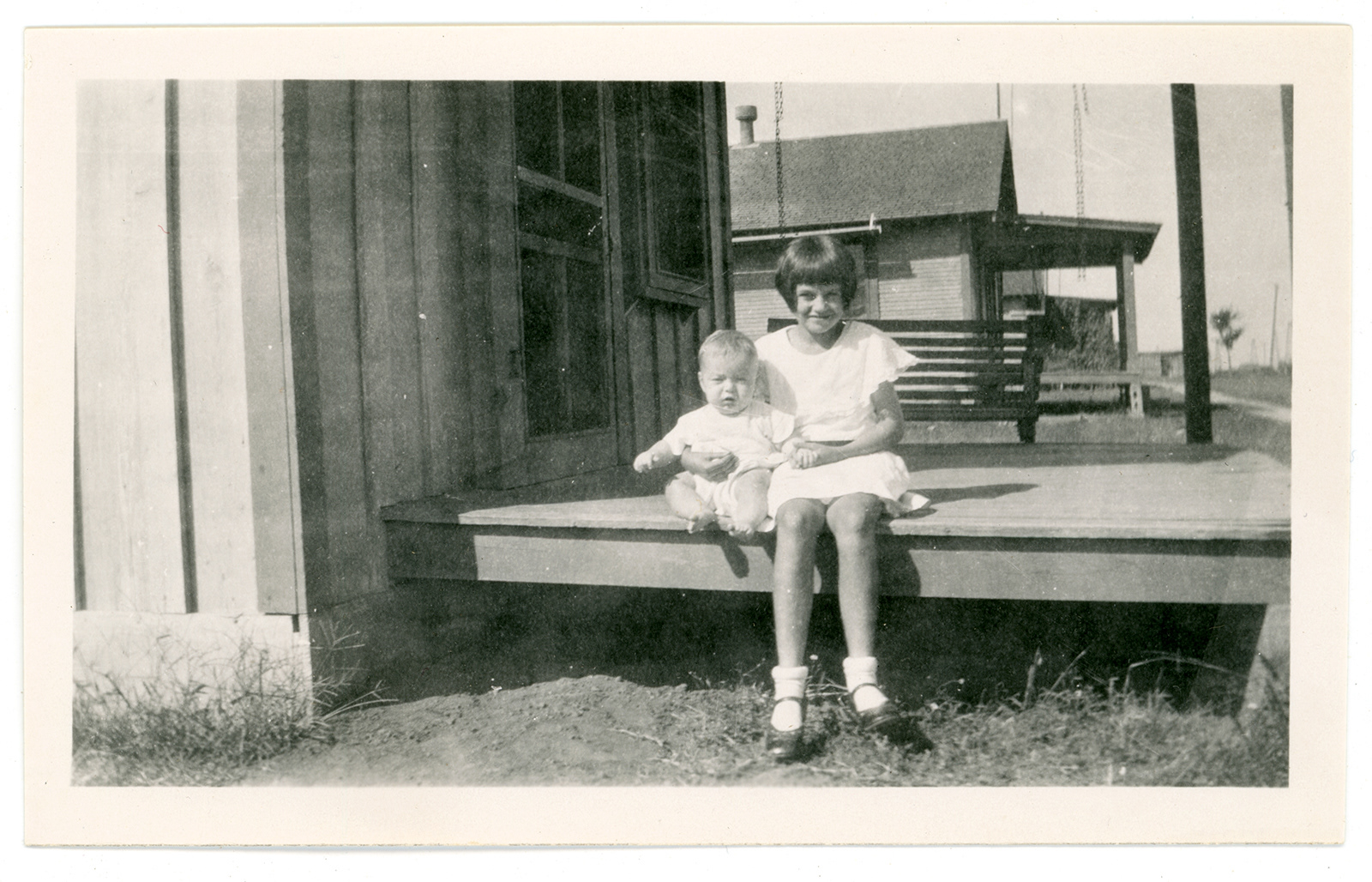

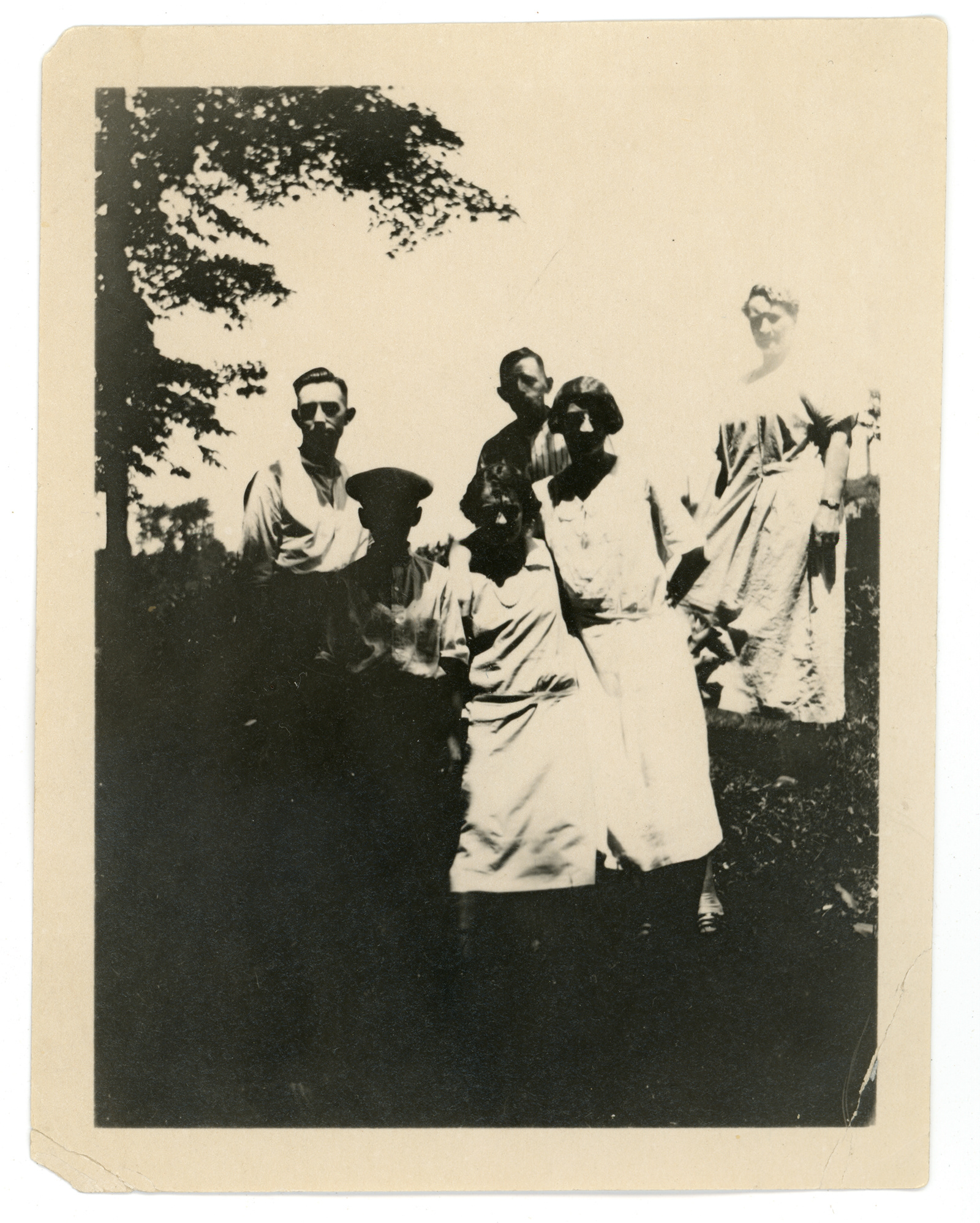

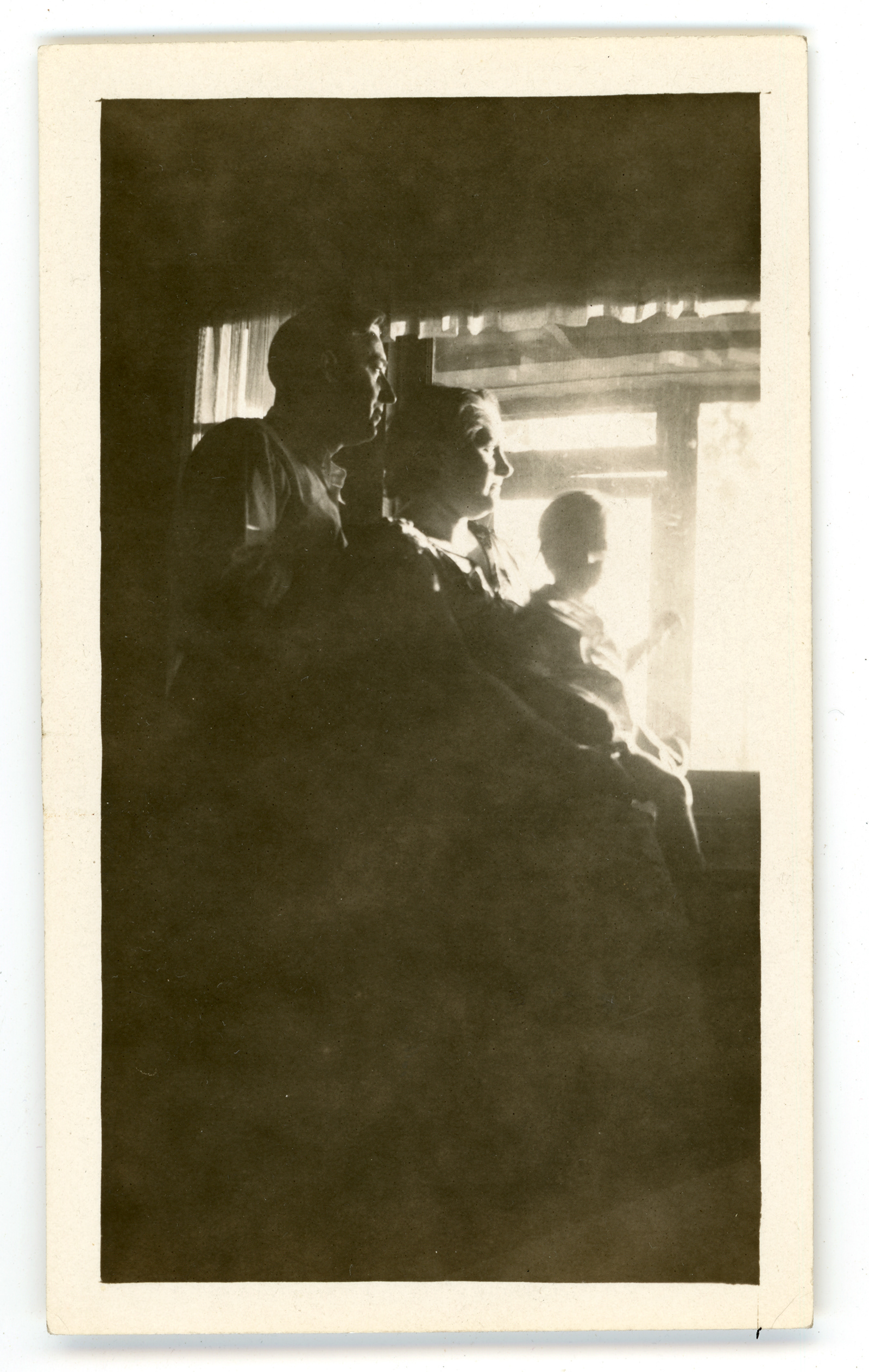

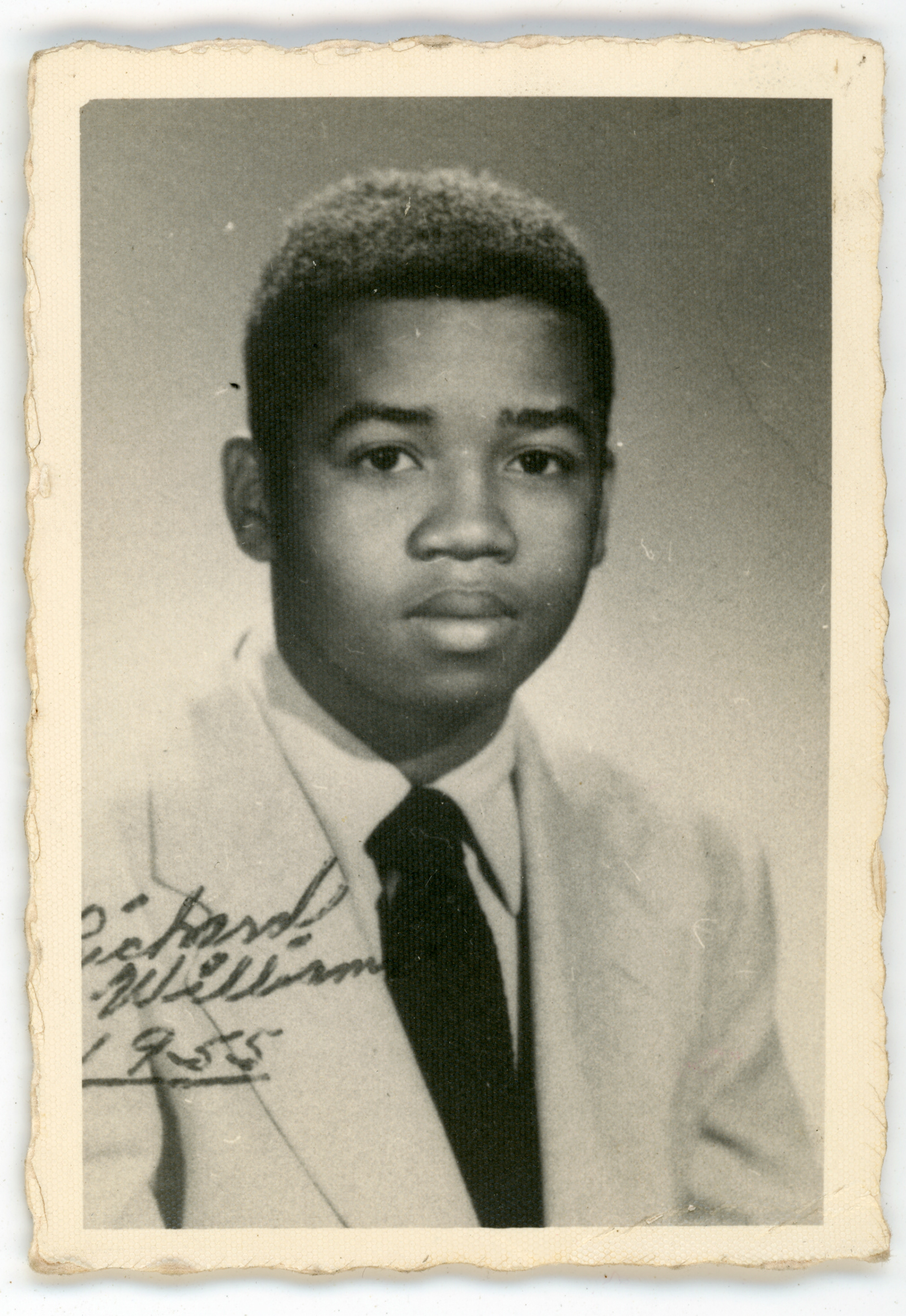

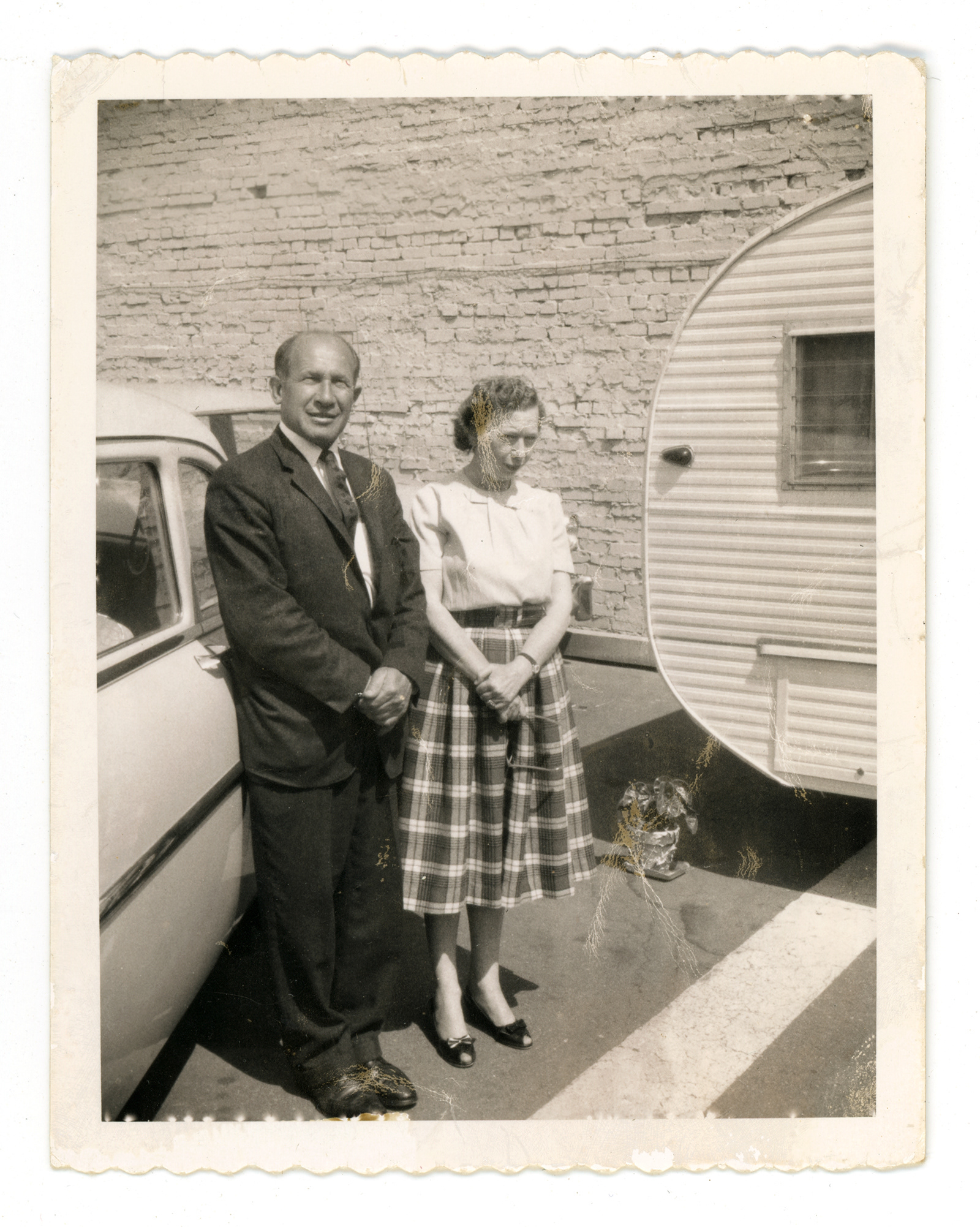

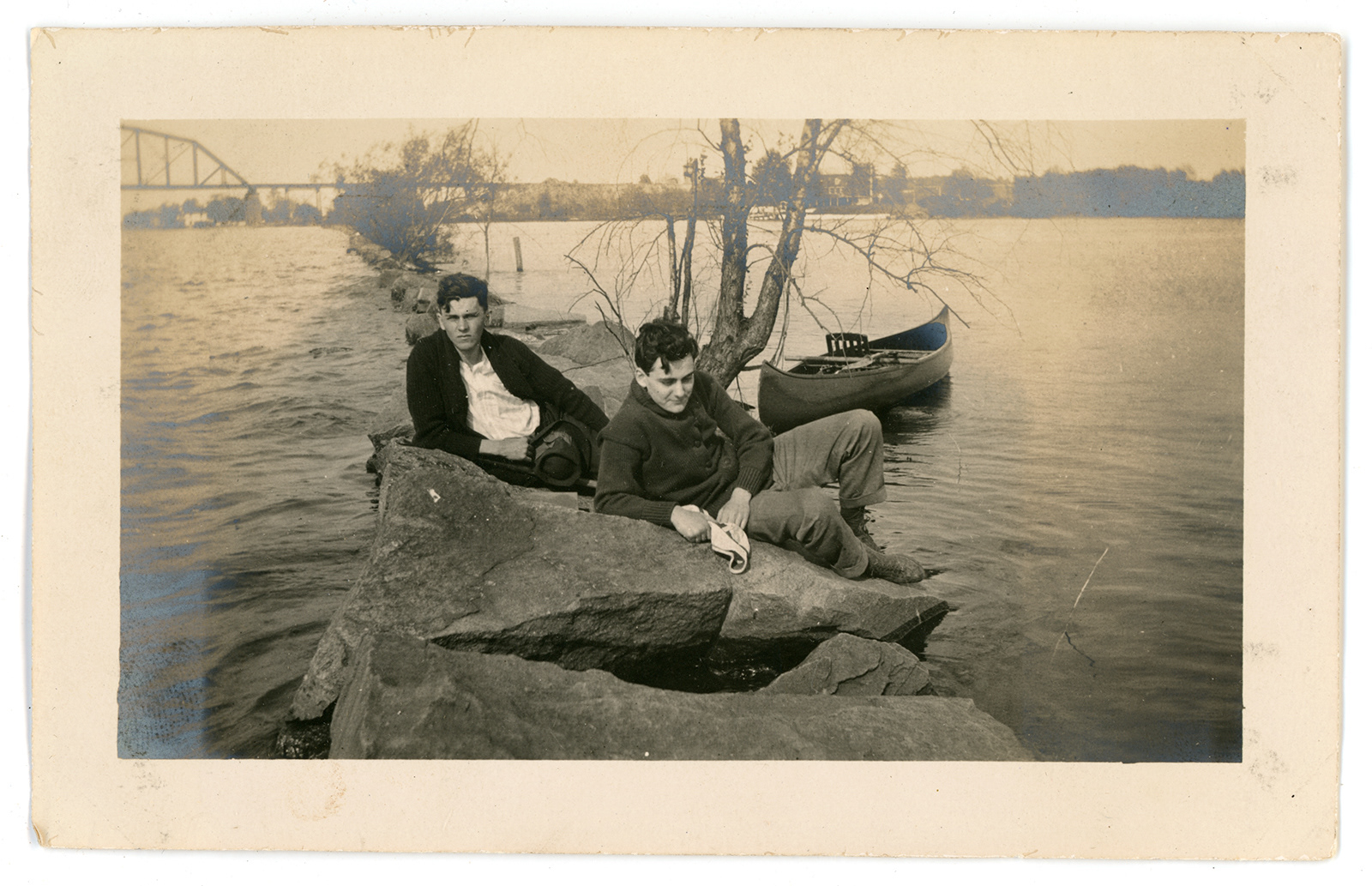

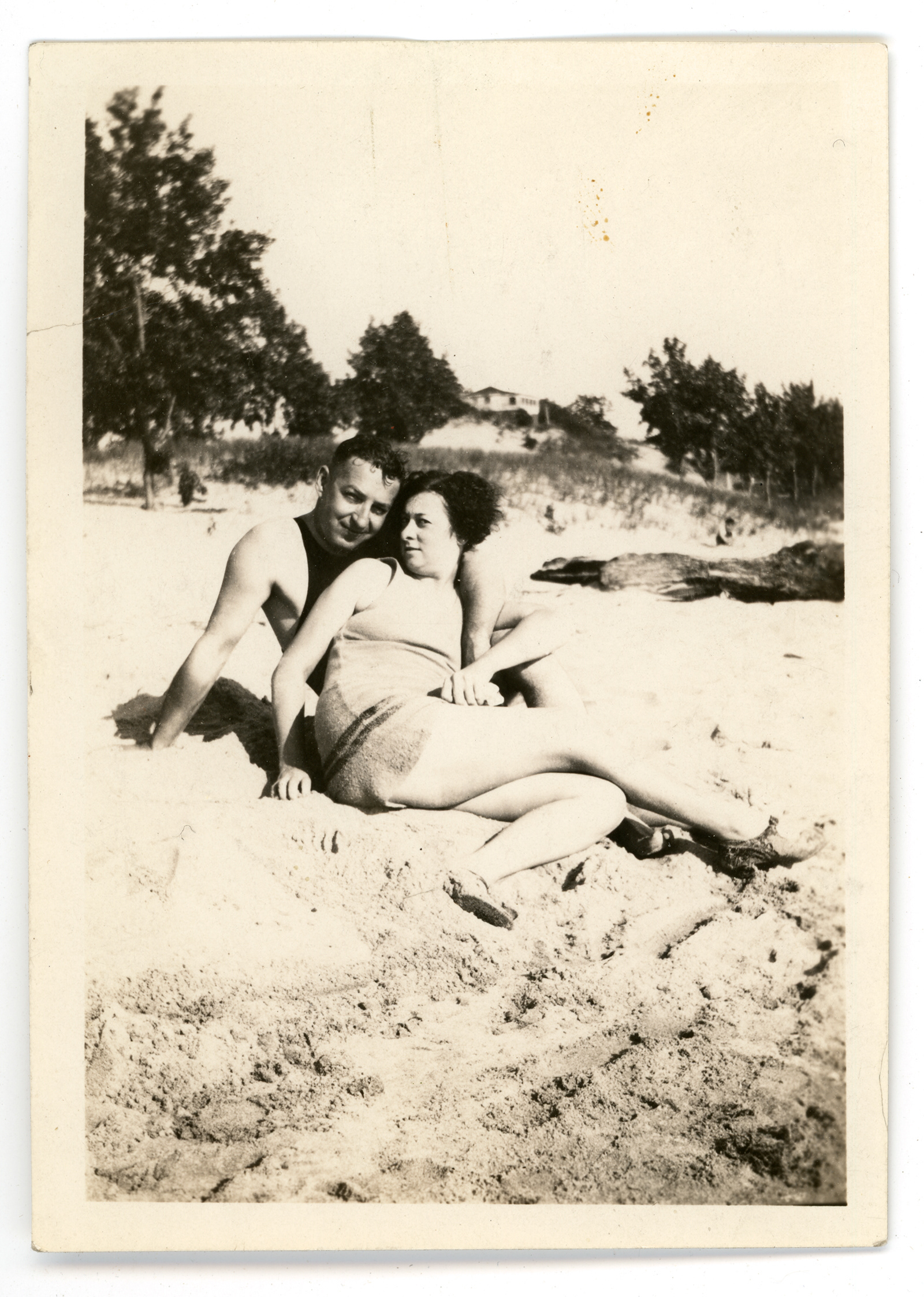

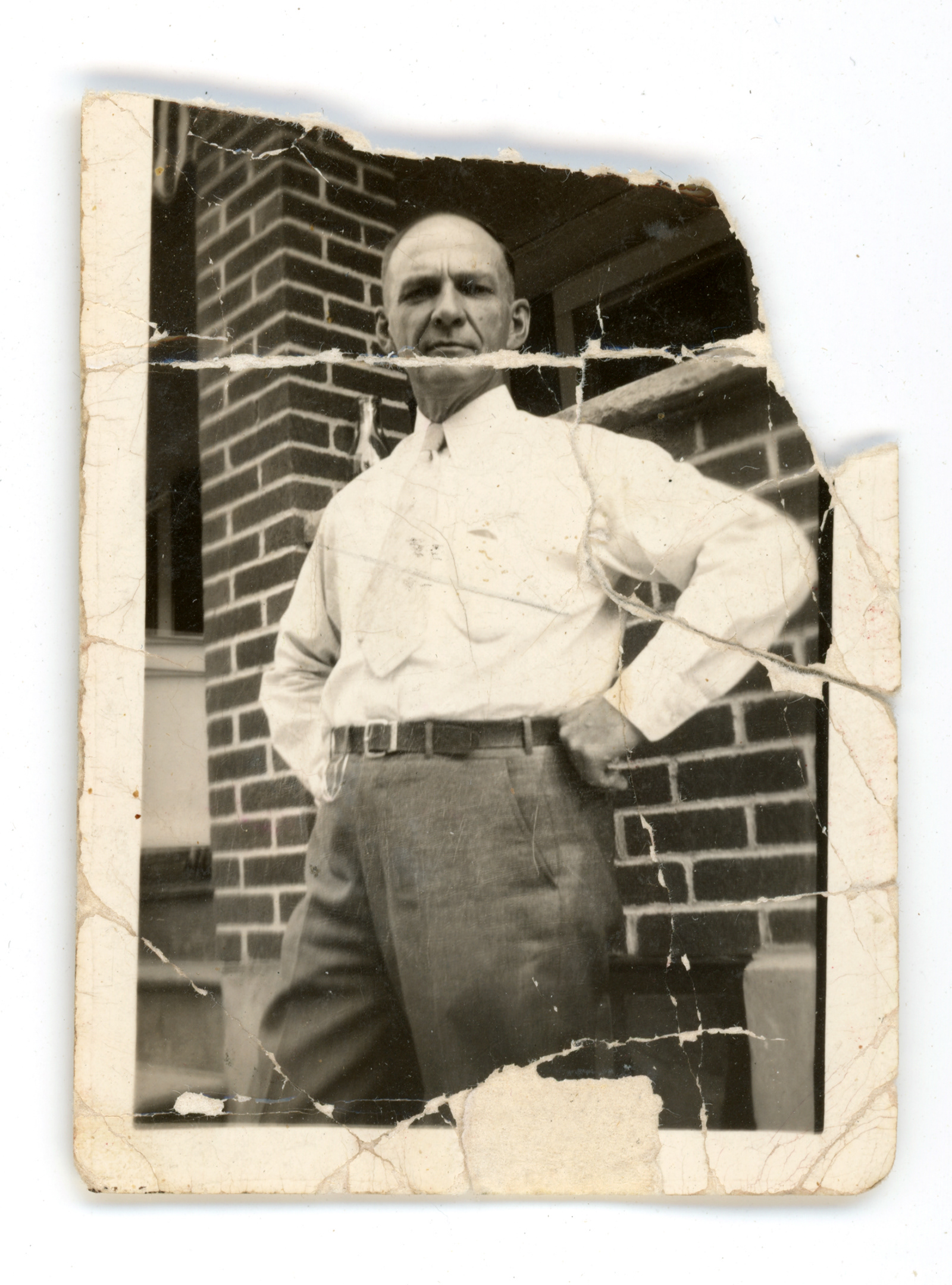

The second source of the images in this sequence is a collection of photographs I have purchased along my travels in the U.S., in flea markets, second-hand and antique shops, pictures dating to the middle decades of the last century. All of these photographs are marooned items of culture. They are heirlooms turned into cheap commodities after somehow avoiding the garbage dump when there was no one left to inherit them. Some were made by local photo studios, more come from ordinary people wielding consumer-grade cameras for the sake of family albums and scrap books shared on kitchen tables and on laps. In many ways, these vernacular pictures are the opposite of my view-camera photographs. They are quick, sudden, non-deliberative—an instantaneity that now bites with anonymity and love whose day has decidedly passed.

And so with these two streams of images, my strategy for approaching inner America has three parts: the particular probing receptivity of the large camera, a curiosity for the alternately confessional and confessionless appeal of photographs of strangers, and the induced dialectic between them, through which the invisible may begin to appear in the mind’s eye. It seems obvious enough but still worth saying that this work, by definition, is open-ended and inconclusive, a mode of exploration suited to quixotic journeys and to mourning alike.

And just so, the American political experiment is approaching its 250th year, the revolution of 1776 still incomplete—the Declaration of Independence’s self-evident truths still not evident to me, I who was born and raised in their shadows. Those shadows have grown longer and longer in my lifetime. At this moment, the United States has reached the highest degree of wealth concentration and income inequality in its history. It has likewise reached a state of profoundly concentrated violence—violence in the form of astonishingly sophisticated militarization (whose domestic face is the police); violence in the form of systemic injustice to racial and ethnic minorities, to sexual minorities, to women, to workers, to immigrants; violence in the form of acute poverty, of hunger, of the refusal to treat healthcare and housing as human rights; violence in the form of environmental devastation; and not least, violence in the form of the combat cherished as entertainment in popular culture and played out constantly as political theater. And I feel the need to say: none of these forms of violence are objects of visual desire for me in the way that they might be for a journalist, or for a photographer who believes that photographs are as good as the messages they can be distilled into. I am not that sort of photographer. History figures in ways other than chronicle and report, and apart from genres straightforwardly deemed non-fictive or fictive. A photograph remains a radical object of culture whose poetics seem, still, receptive to the challenges of the moment: an object pressed from one side by history, and from the other side by the light reflecting the surfaces of the outer world.

I make this work with the predicating confidence that any work of art requires to come to exist at all, but with no ability to assess its value, or to know whether audiences actually exist for it. It could well be that the true audiences for this work are the dead and the unborn, and if so—should I count myself among them?

Jason Francisco

July 2020, Atlanta

July 2020, Atlanta

Places appearing in the view-camera photographs in this sequence include:

Valle, Arizona; North Pownal, Vermont; Taos Pueblo, New Mexico; Detroit, Michigan; Pawhuksa, Oklahoma; Winston-Salem, North Carolina; South Bend, Indiana; Youngstown, Ohio; Joseph City, Arizona; East St. Louis, Illinois; Atlanta, Georgia; Toledo, Ohio; Yucca, Arizona; Fall River, Massachusetts; Washington, D.C.; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; Lindale, Georgia; San Francisco, California; Braddock, Pennsylvania; Beaverdam, Ohio; Chester, Pennsylvania; Las Vegas, Nevada; Spring City, Tennessee; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Santa Fe, New Mexico; Sedalia, Missouri; Rossville, Georgia; Aliquippa, Pennsylvania; Memphis, Tennessee; Lake Station, Illinois; Chattanooga, Tennessee; Chicago, Illinois; South Boston, Virginia; Spartanburg, South Carolina; Tucumcari, New Mexico; Gary, Indiana; Knoxville, Tennessee; Hominy, Oklahoma; Boron, California; Taos, New Mexico; Cowpens, South Carolina; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Sale Creek, Tennessee; Shepherdsville, Kentucky; Adrian, Texas; Kingman, Arizona; Worcester, Massachusetts; Uniontown, Pennsylvania; Terre Haute, Indiana; Nashville, Tennessee

With thanks to Alexander Nemerov and Asya Gefter, who in different phases of my travels were true companions.