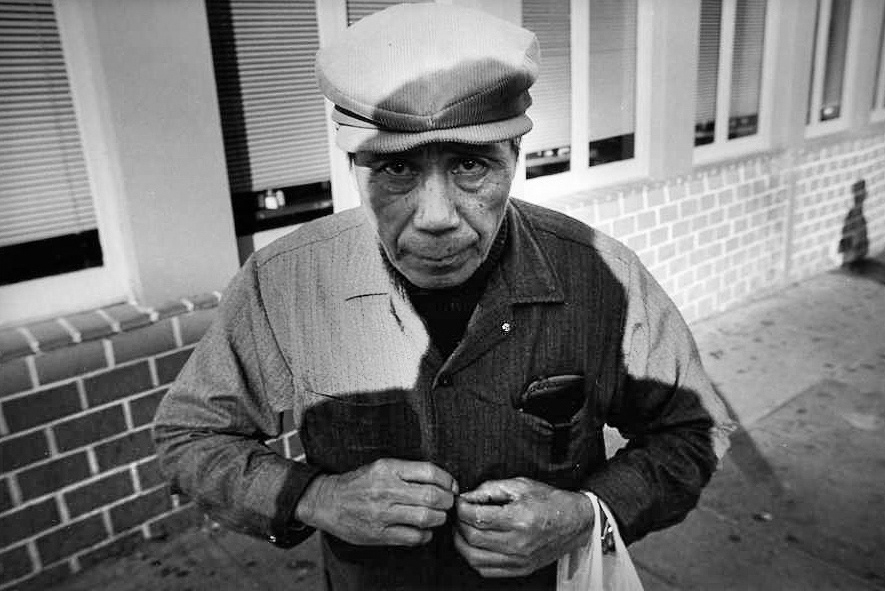

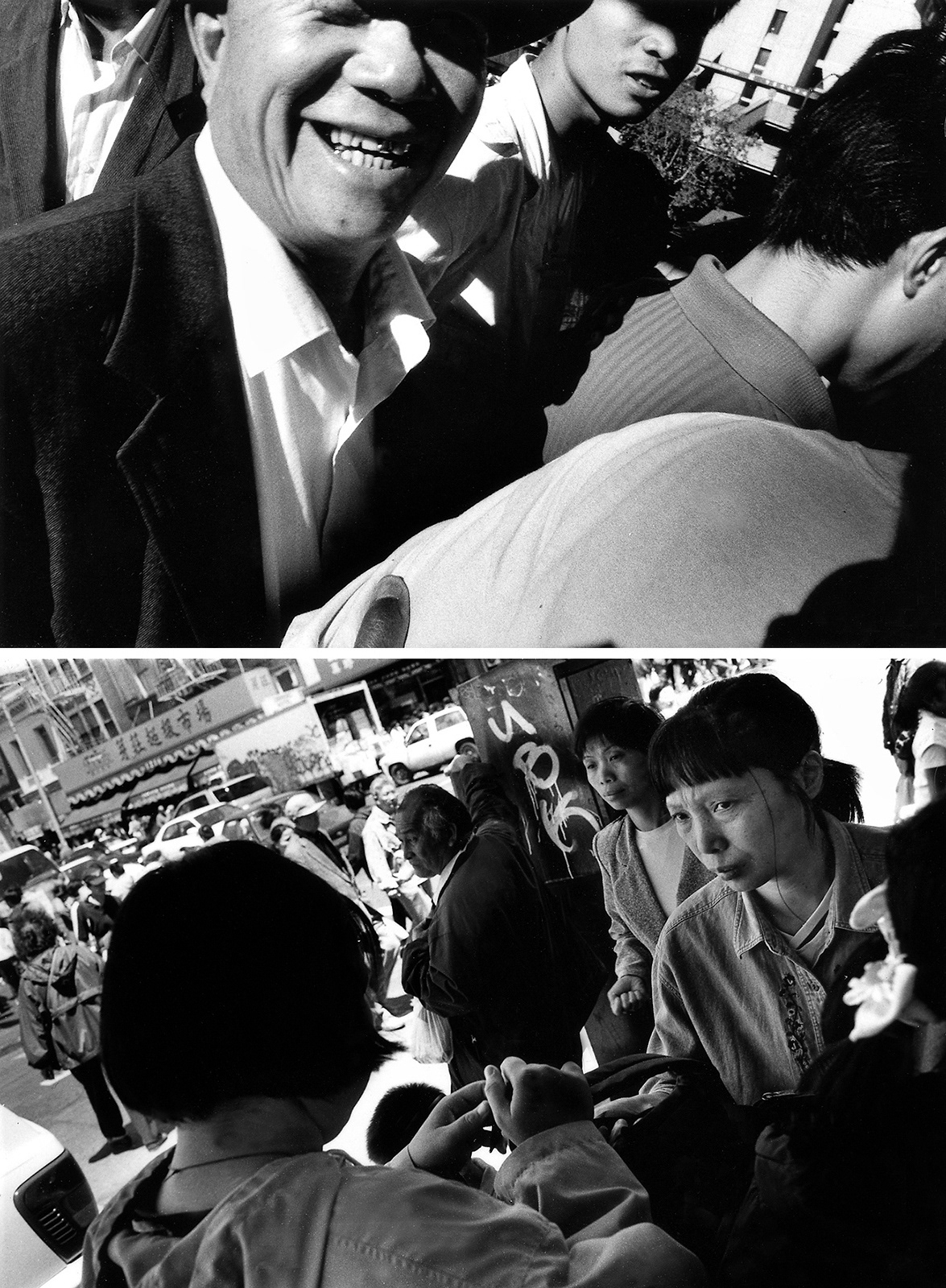

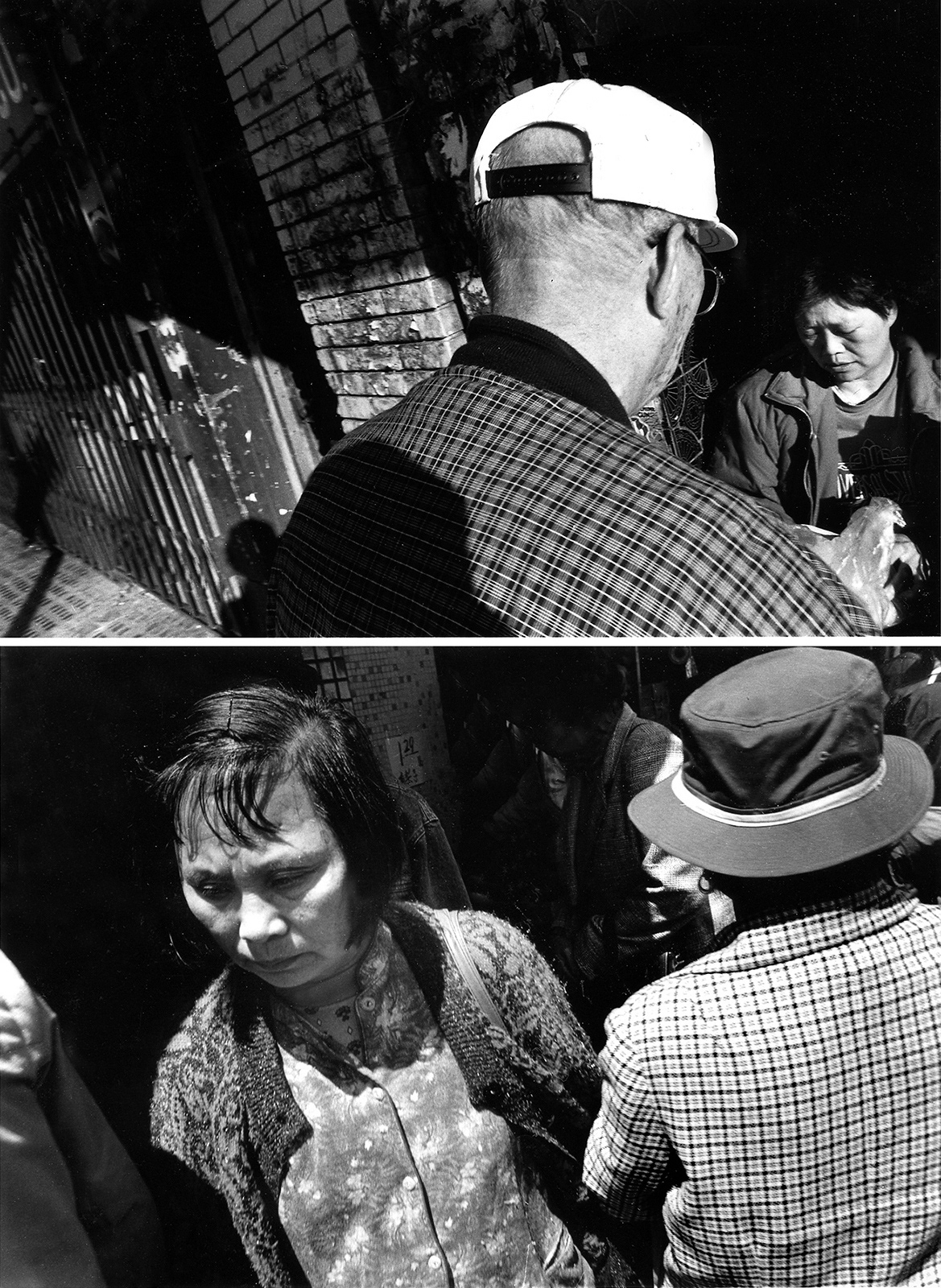

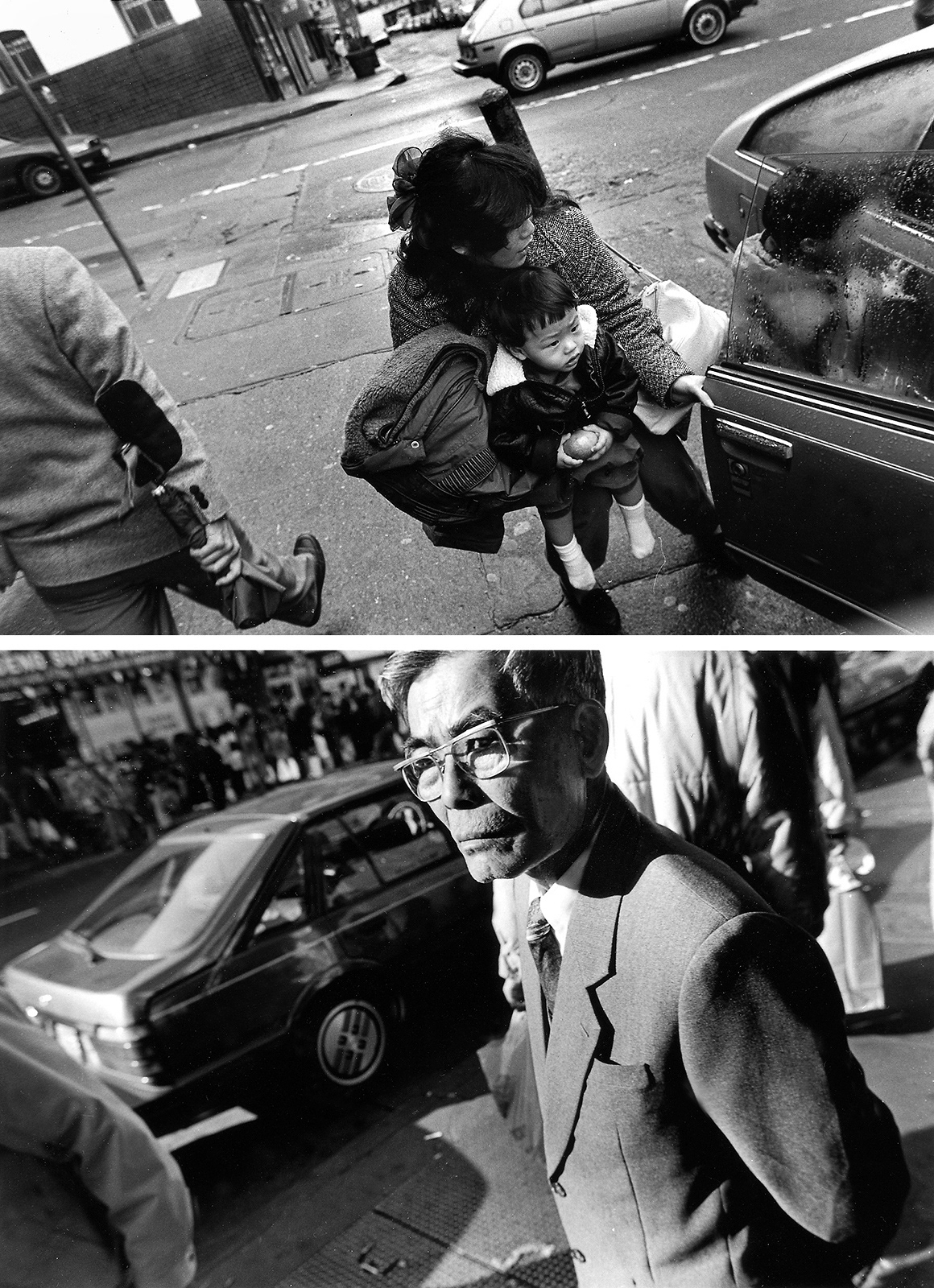

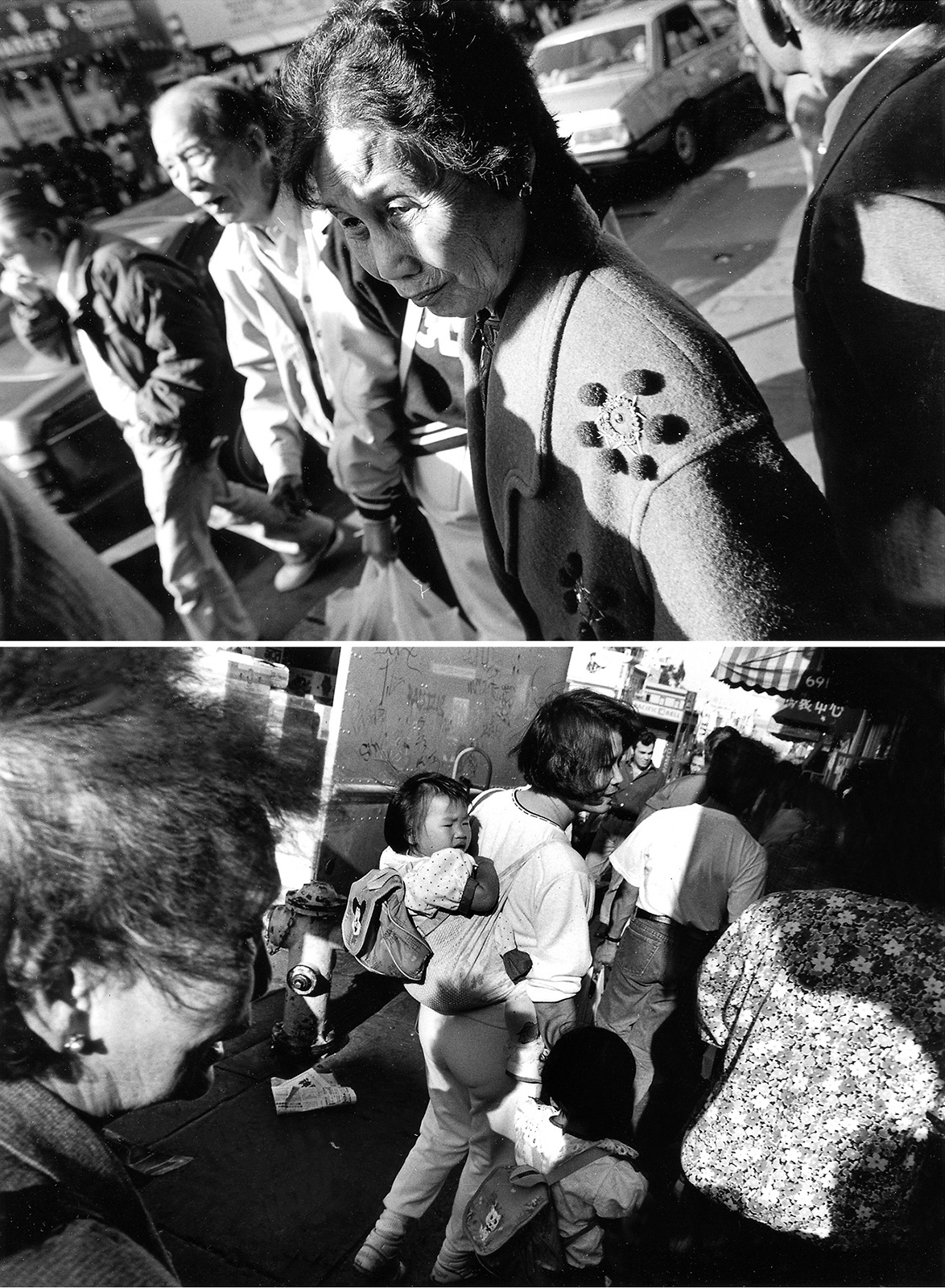

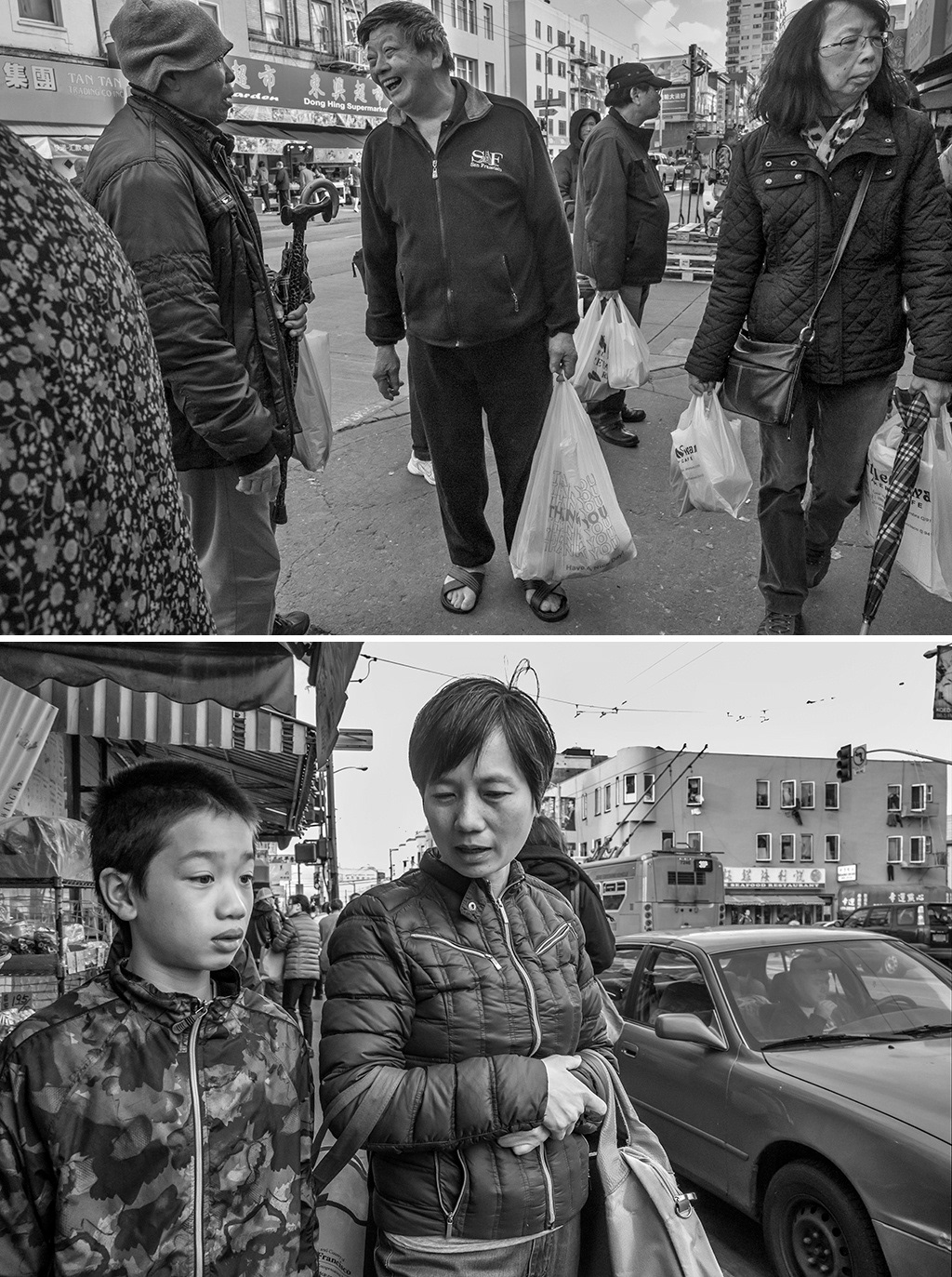

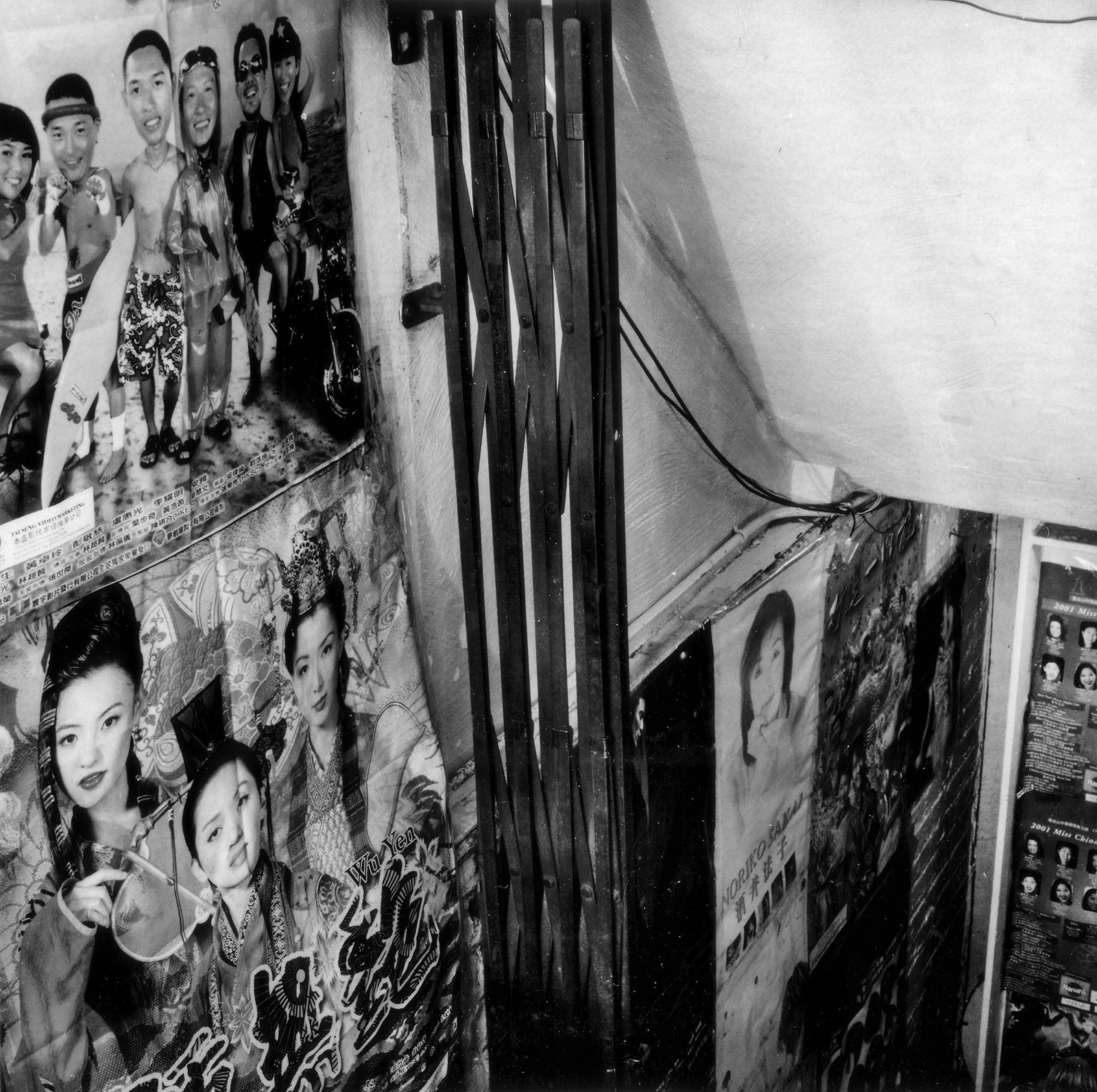

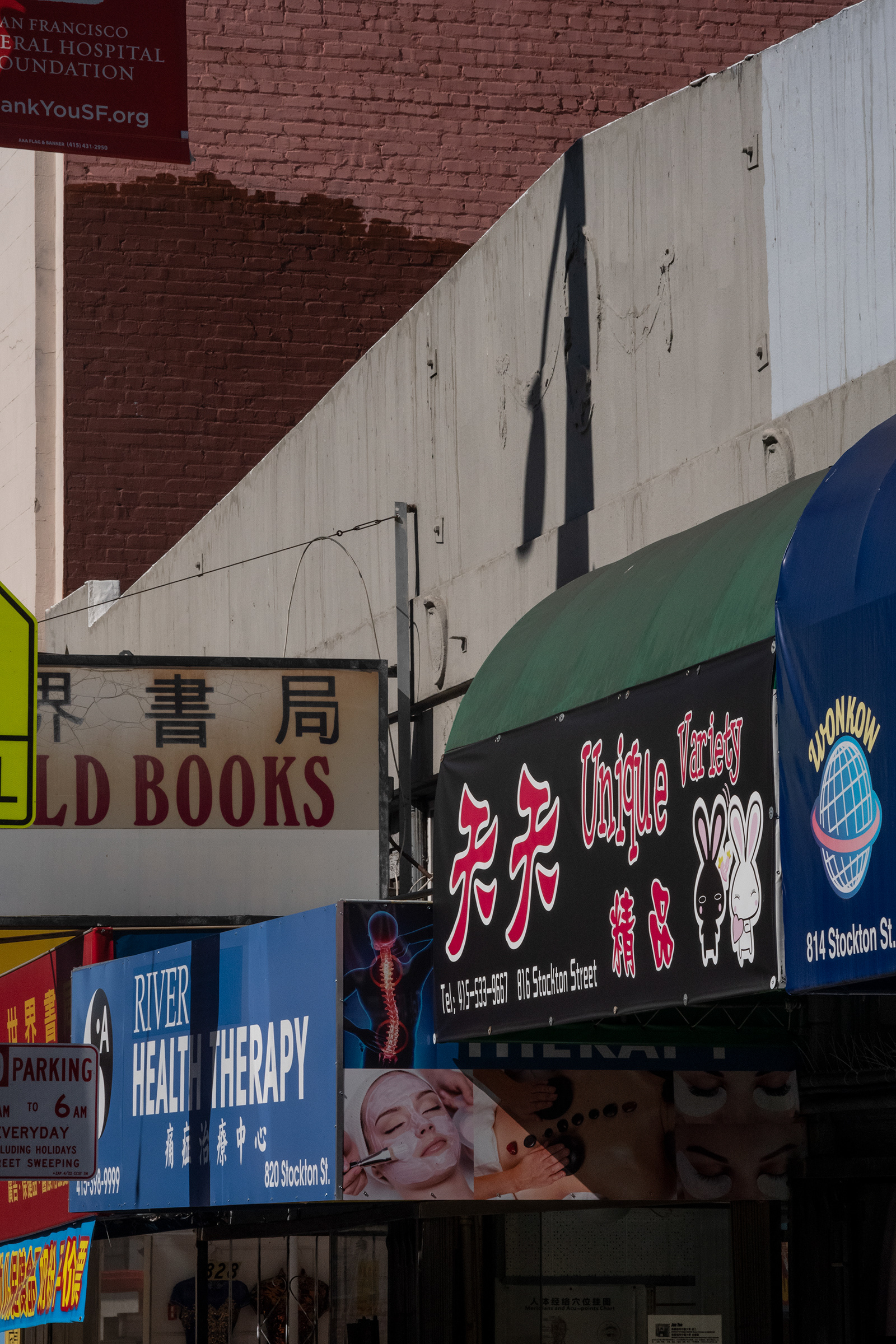

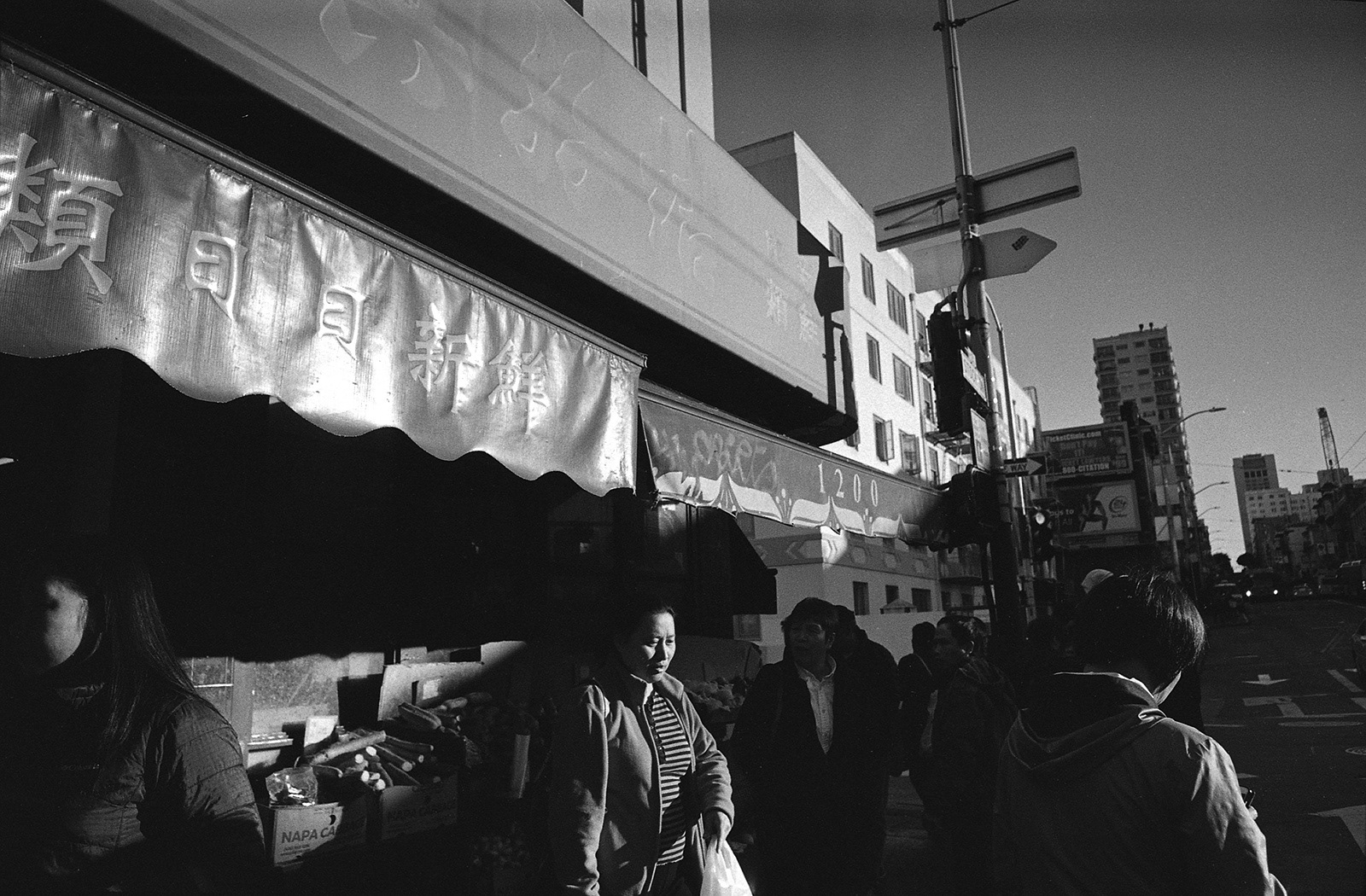

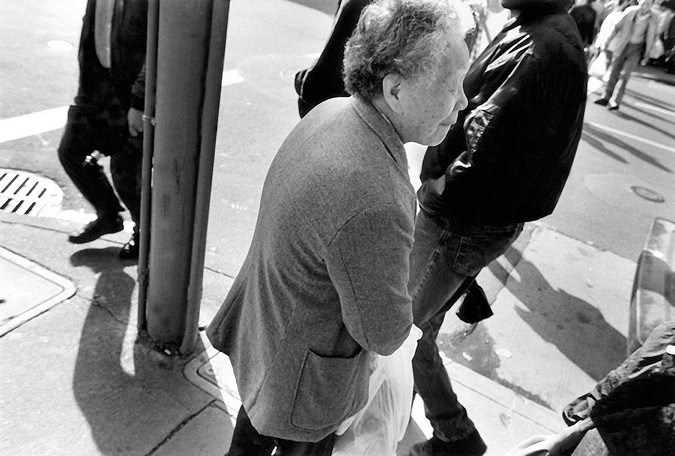

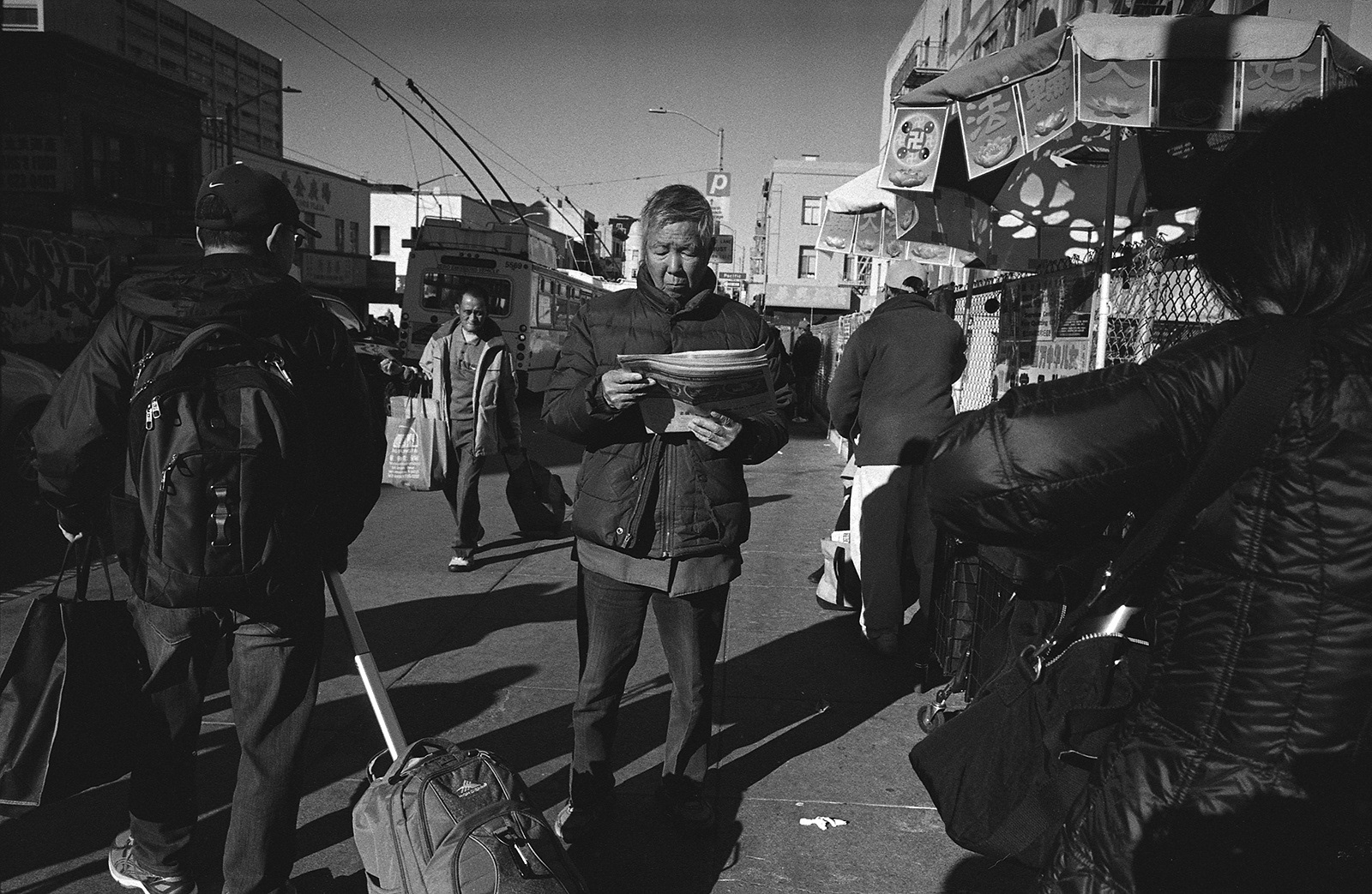

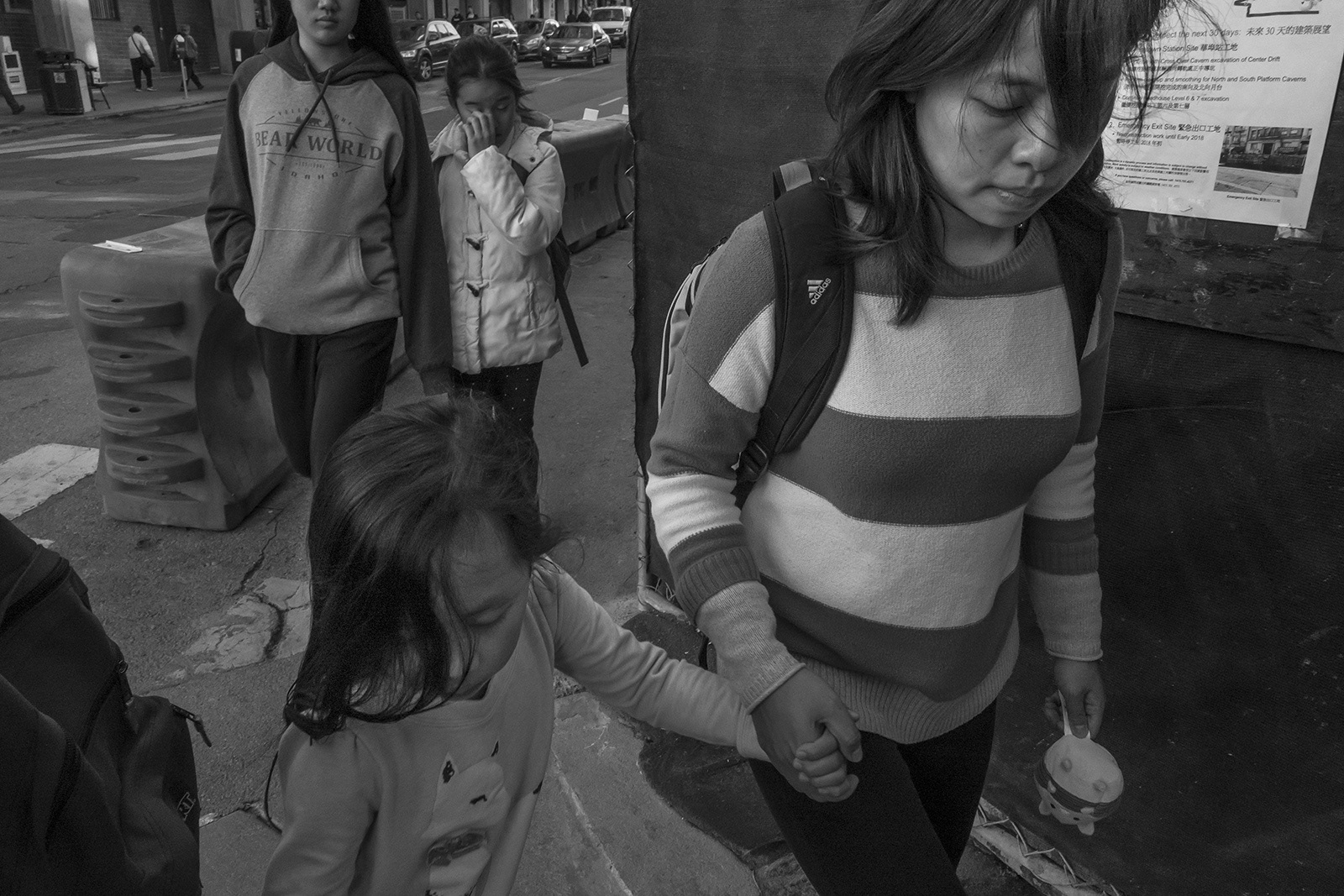

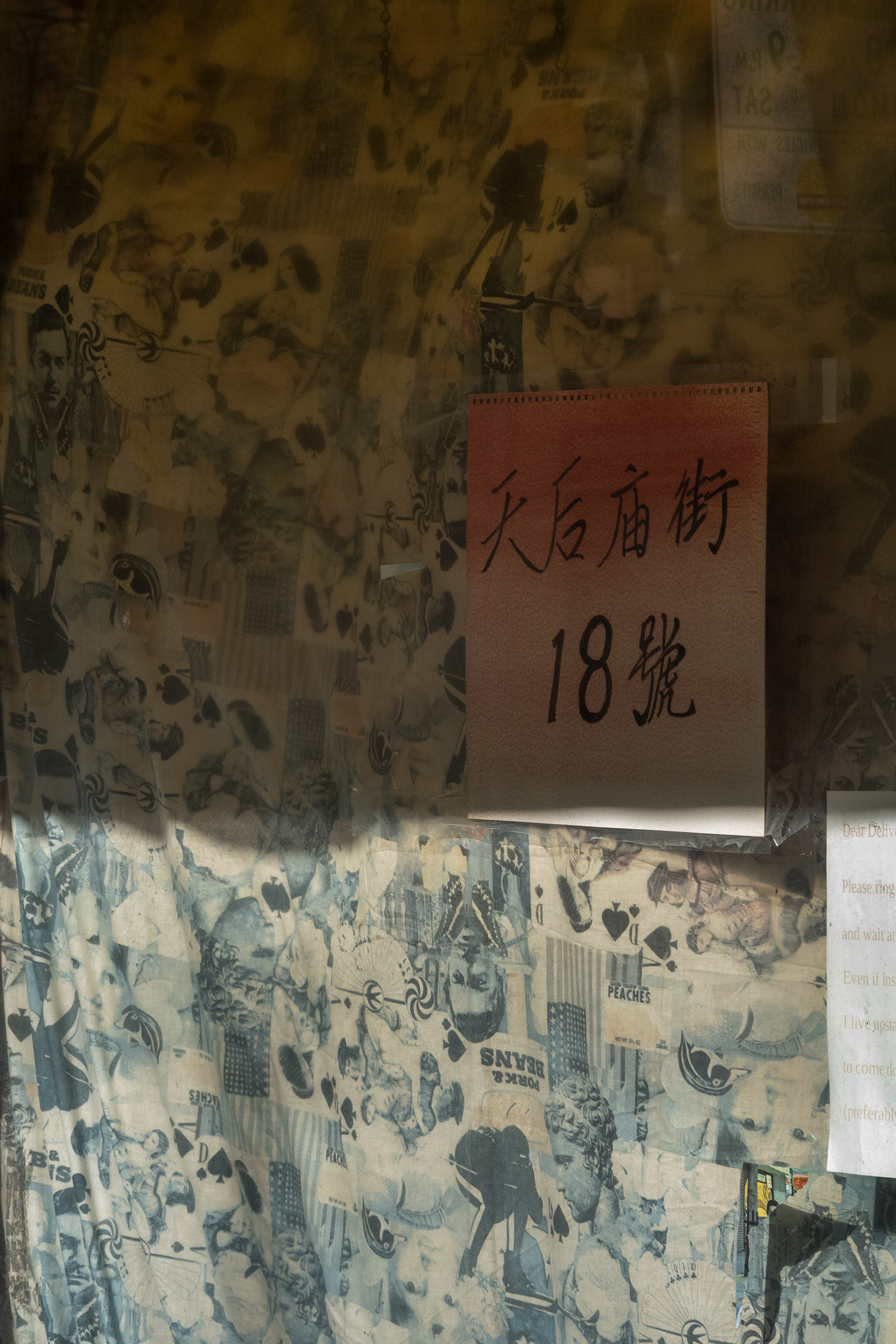

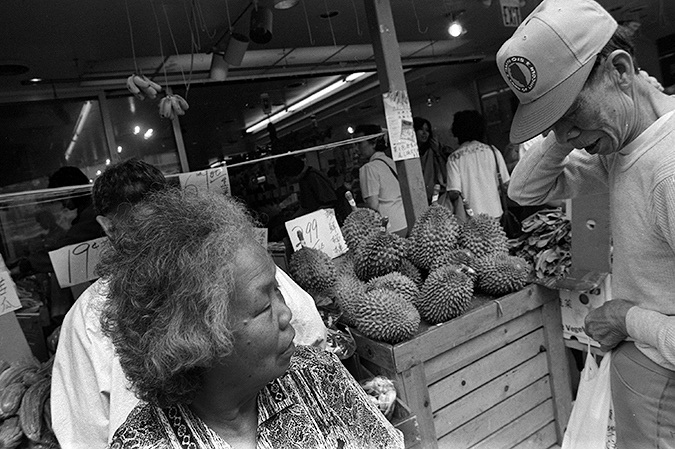

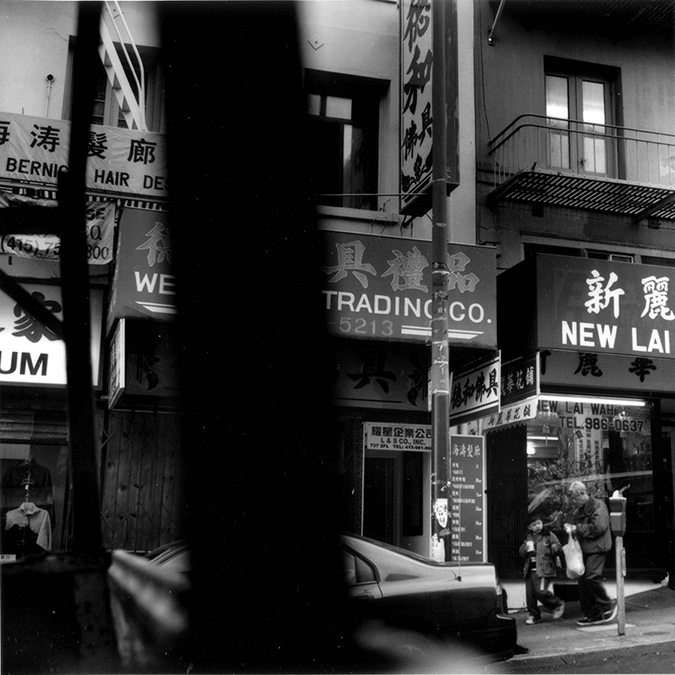

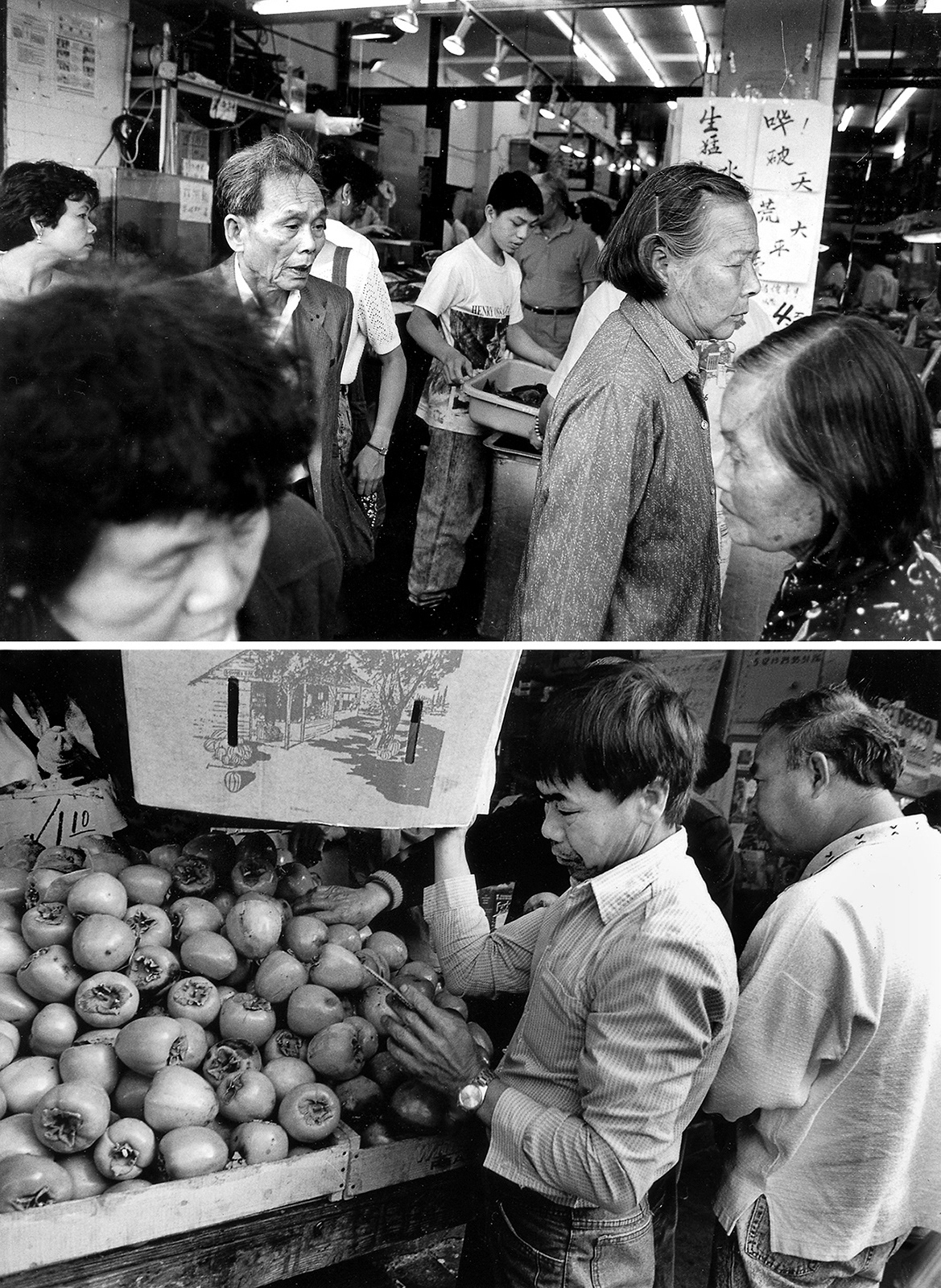

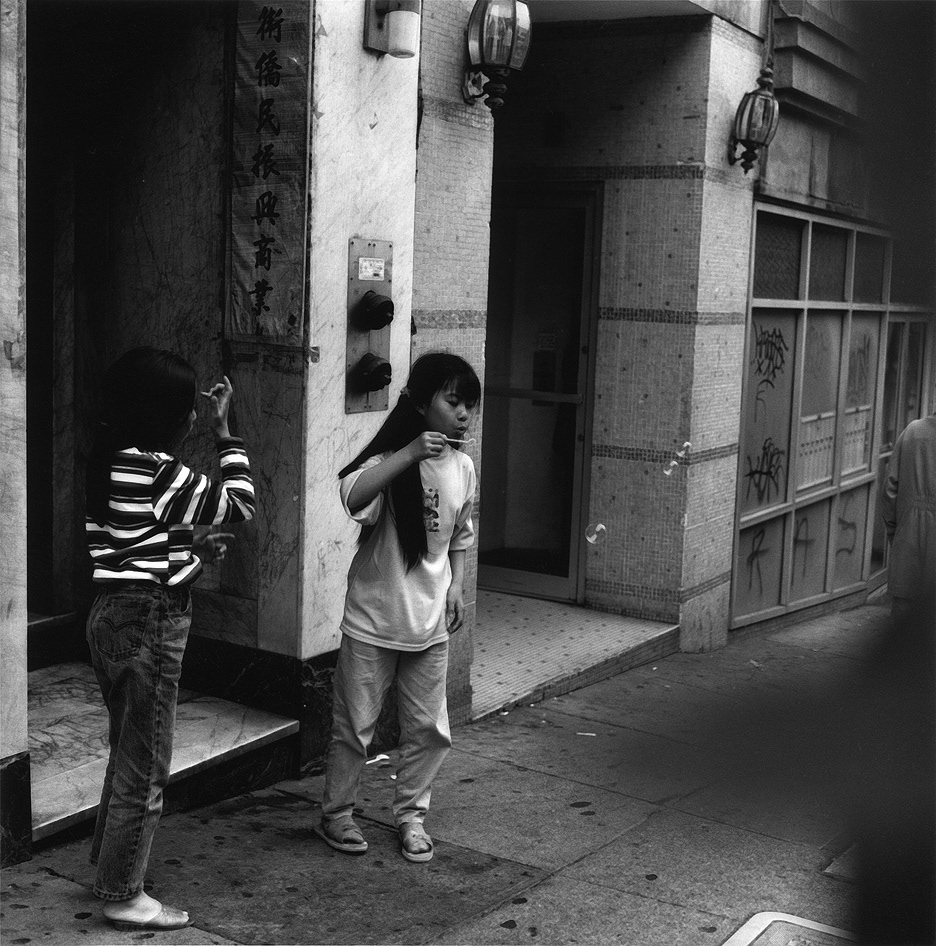

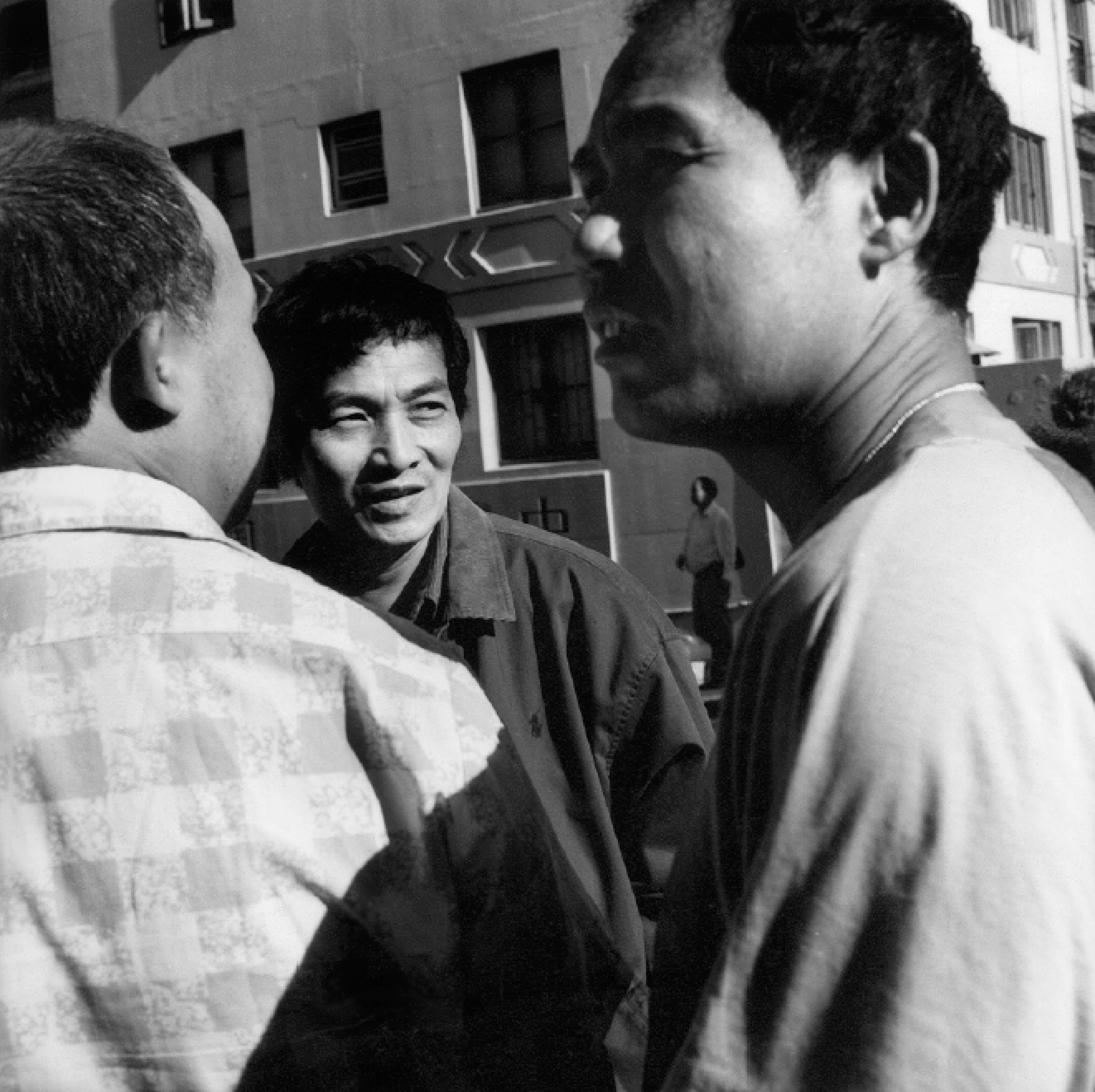

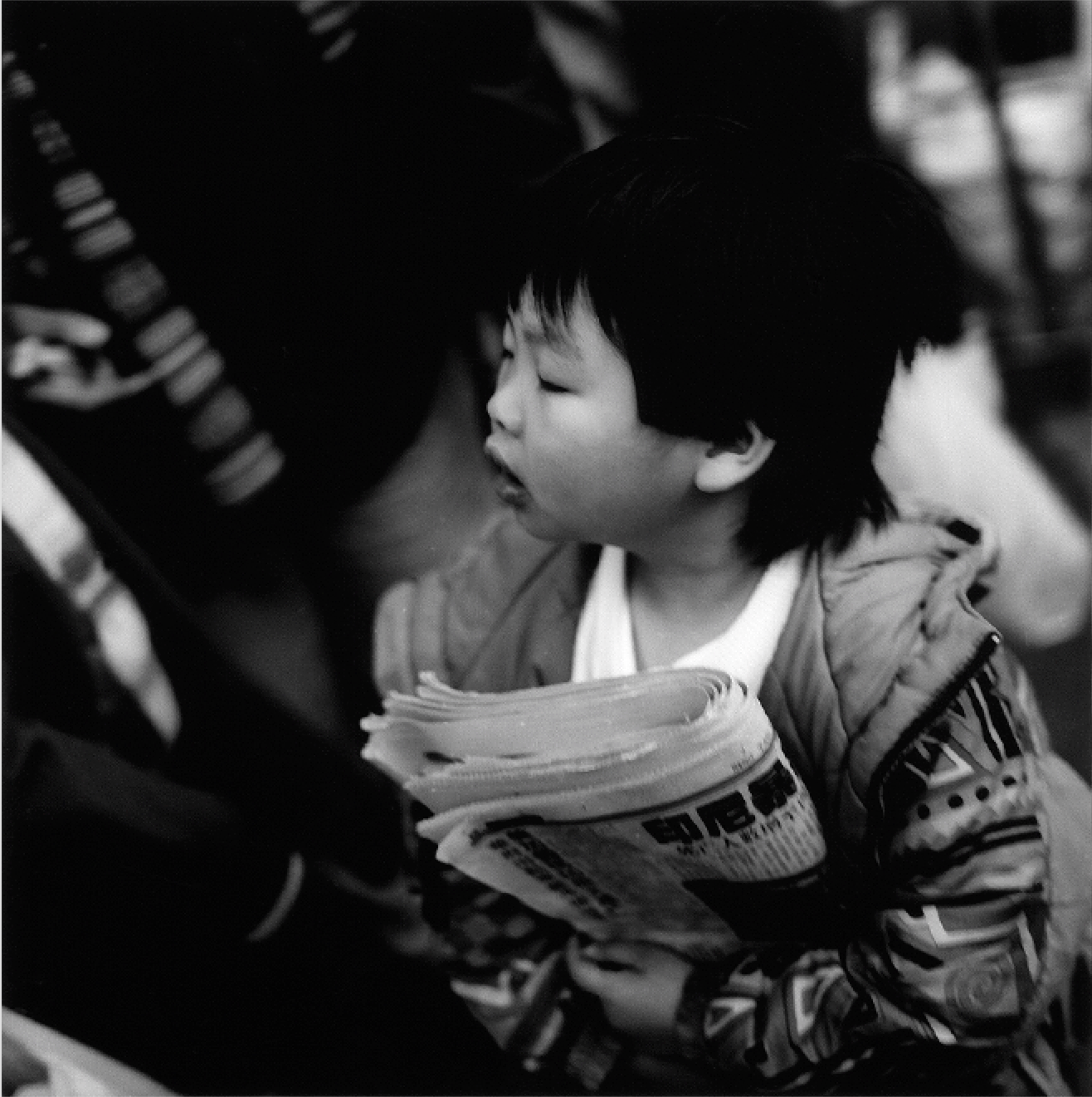

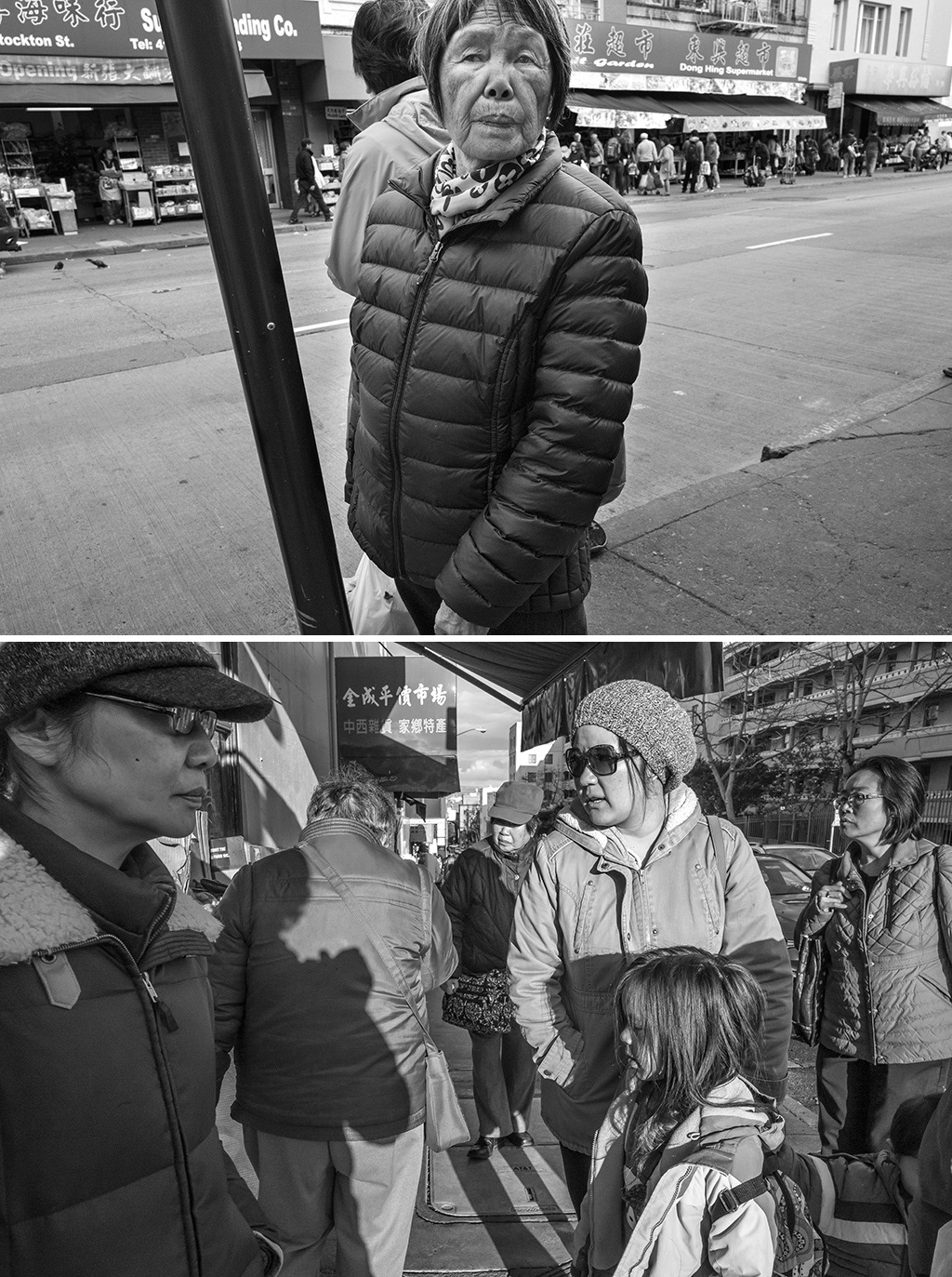

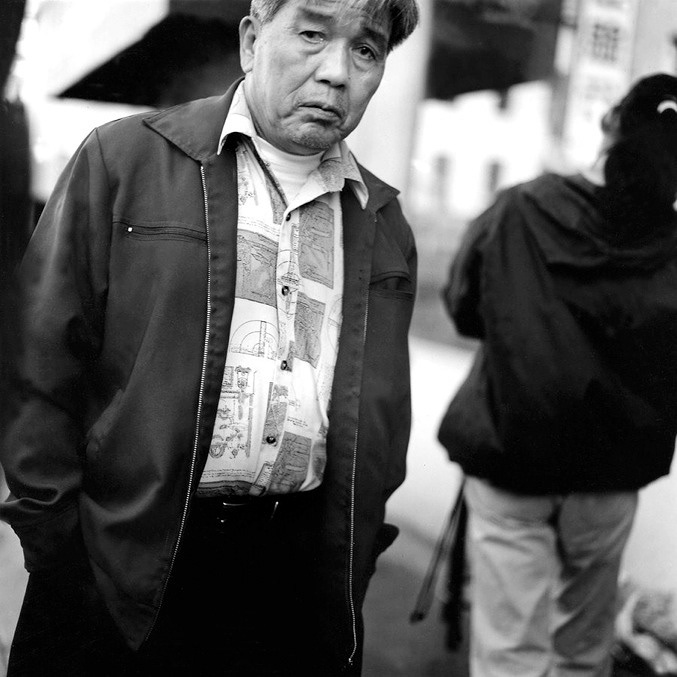

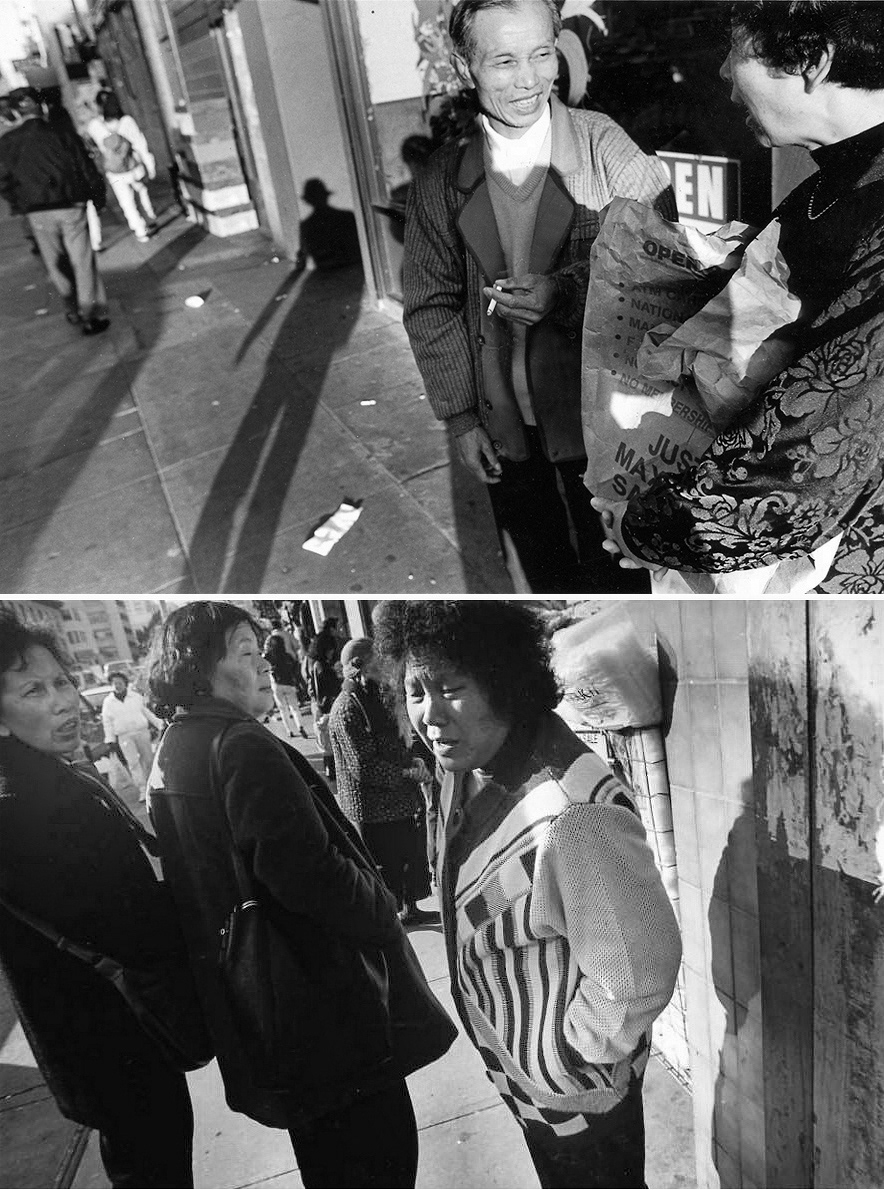

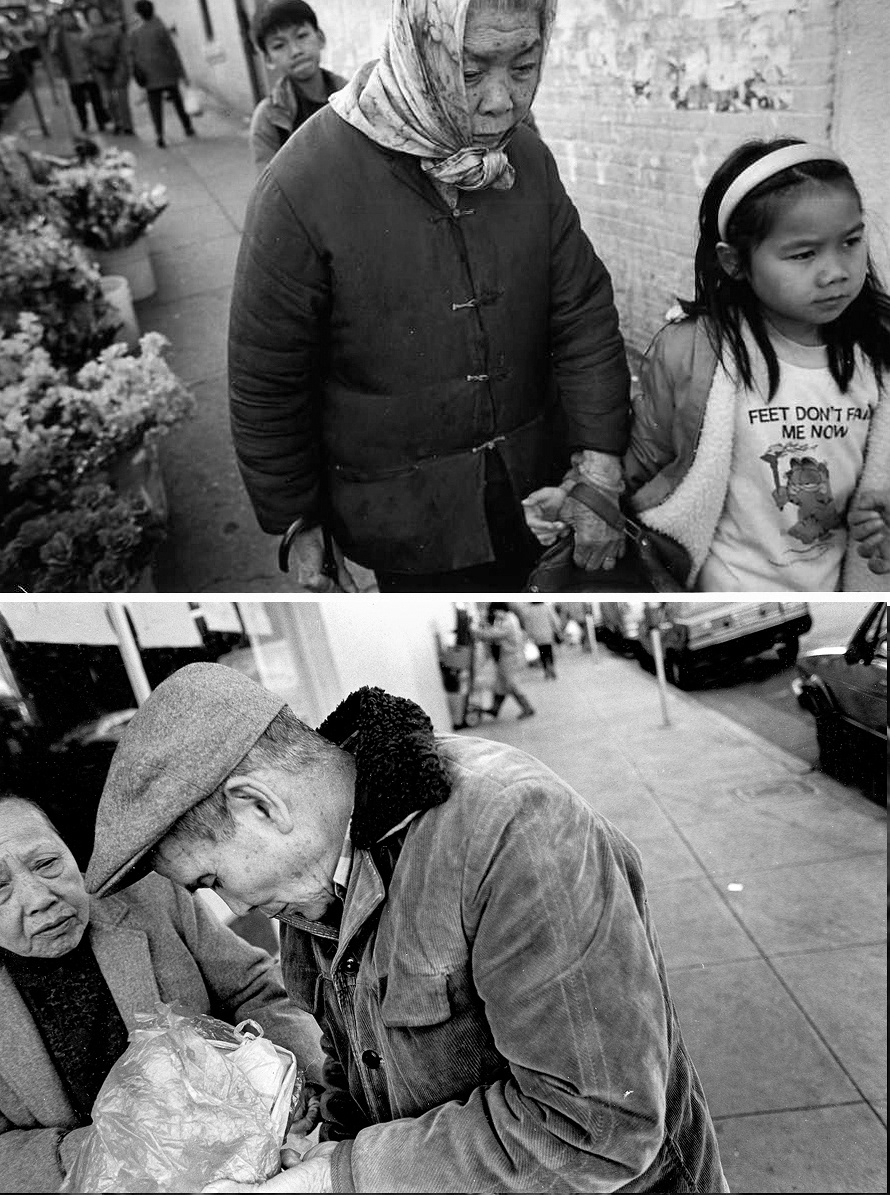

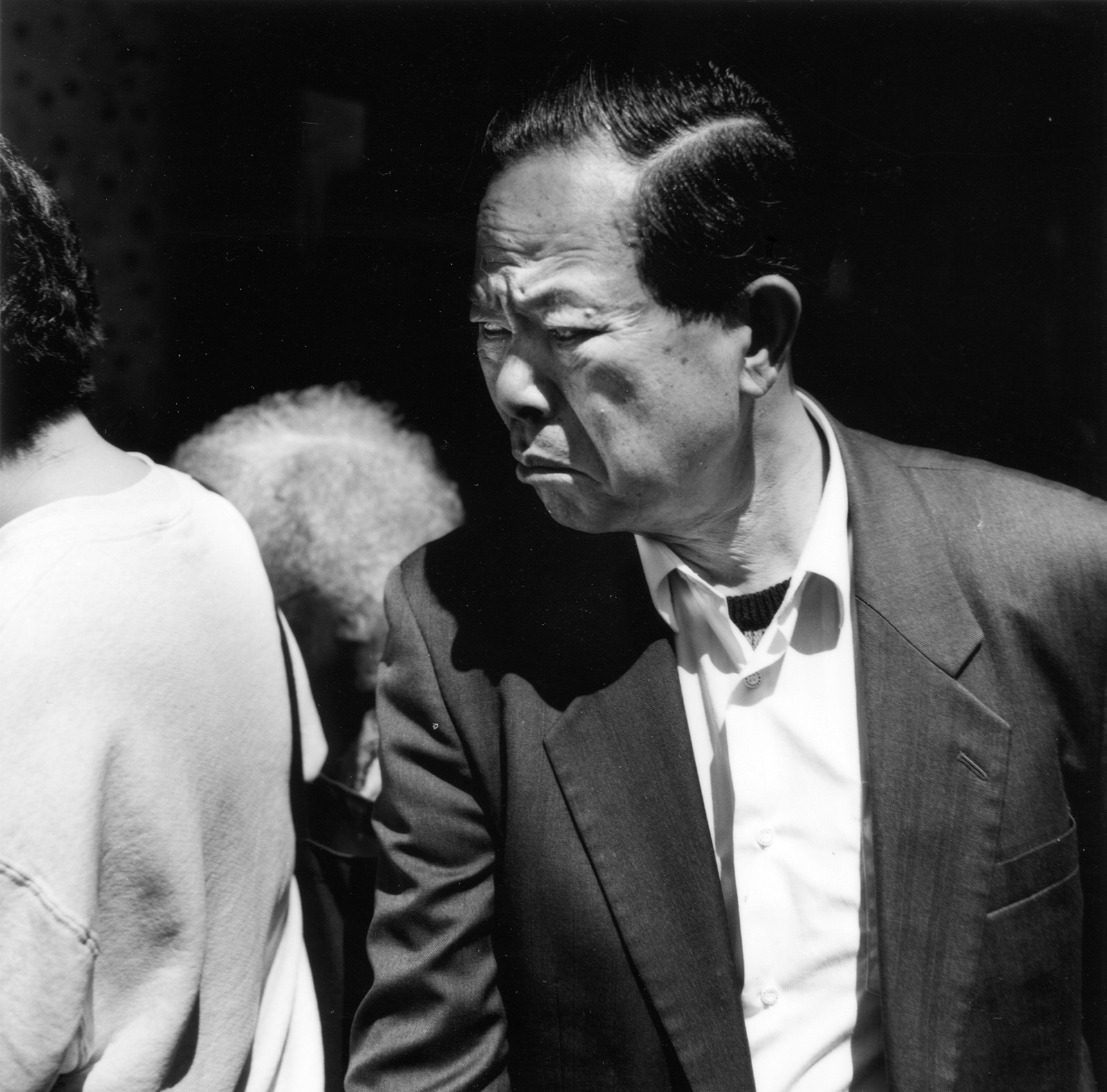

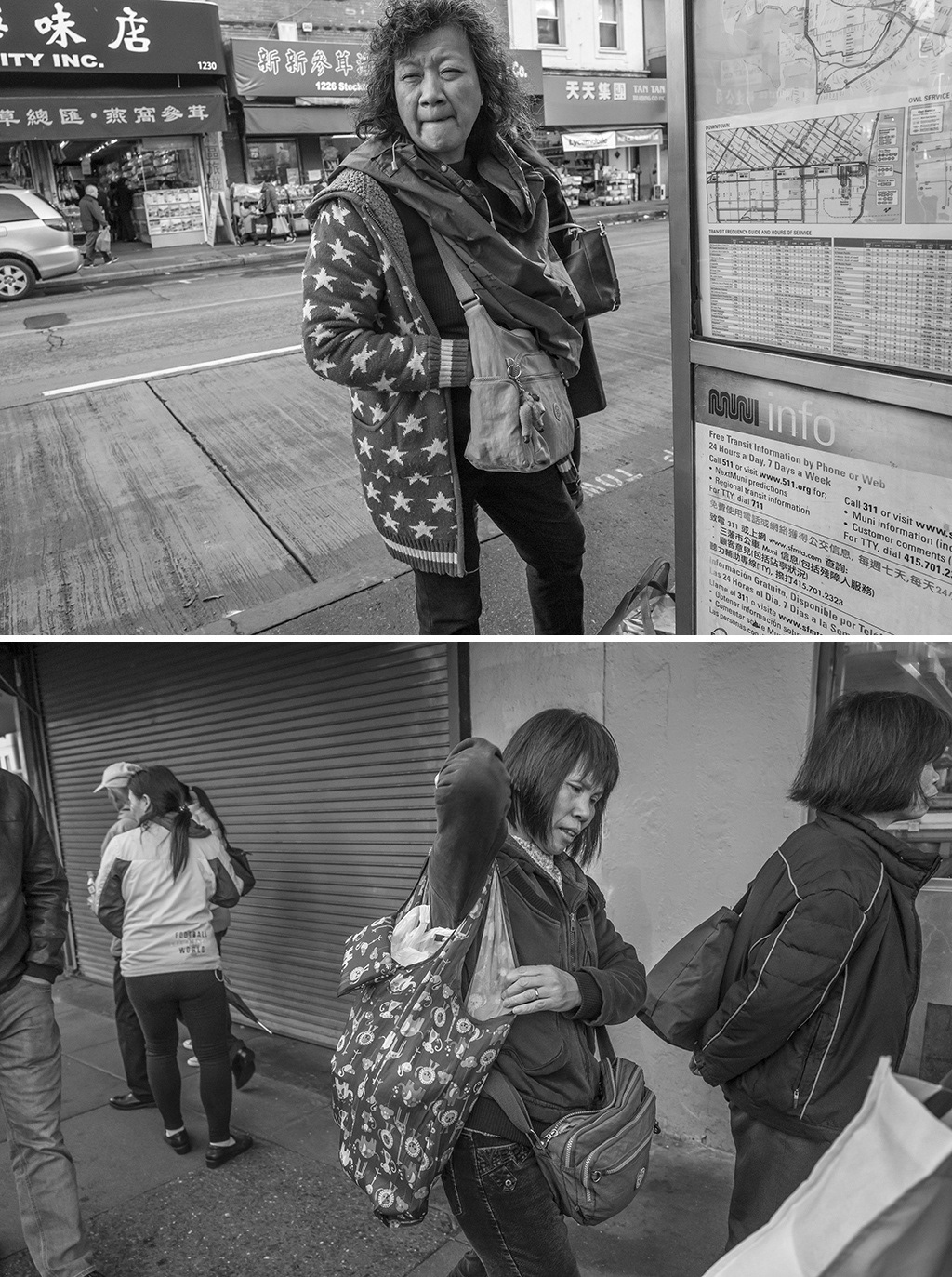

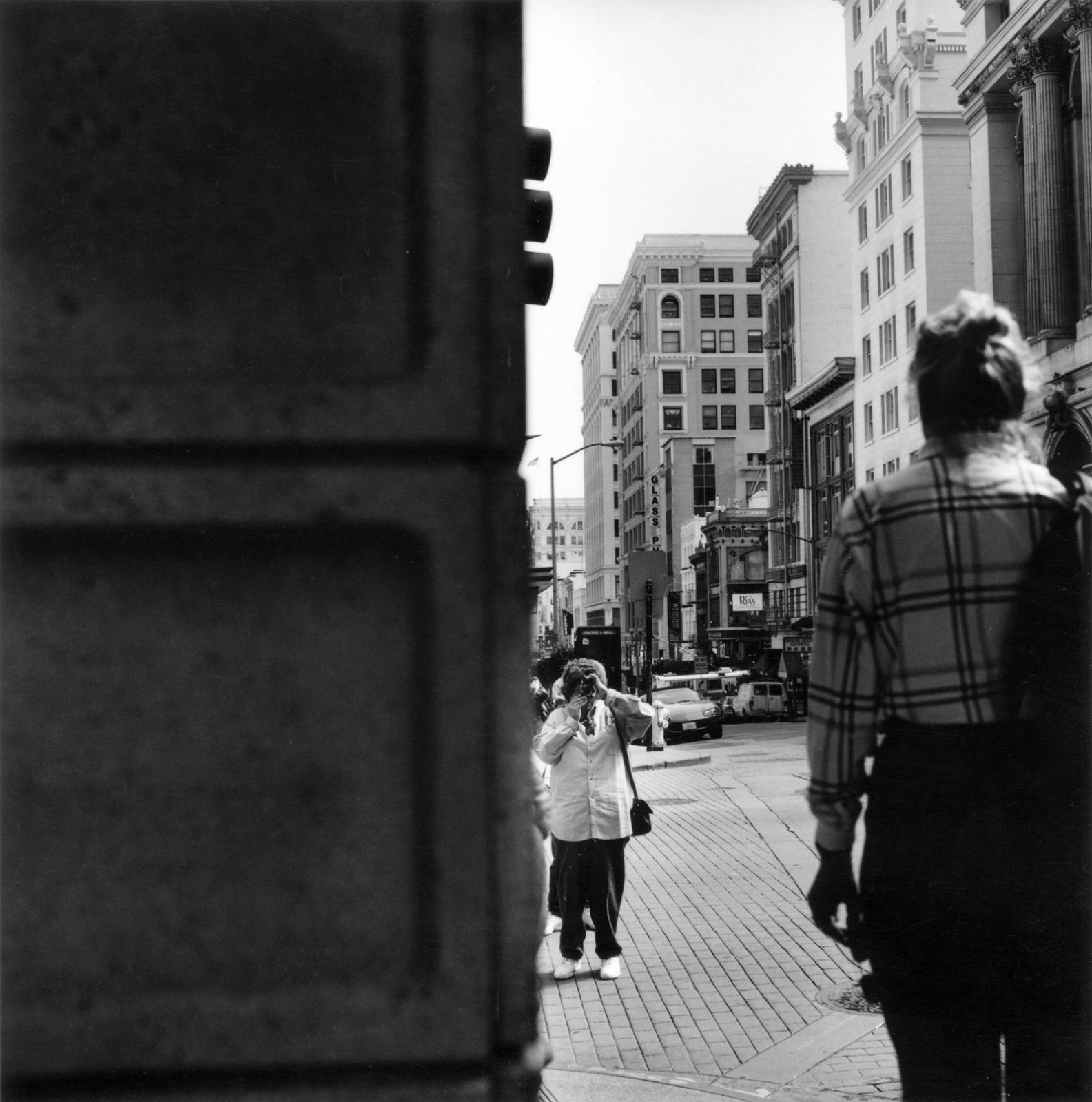

Big City (1989-2022) is a visual meditation on San Francisco’s historic Chinatown, an important American place colloquially known in Cantonese as Dai Fao ("Big City"). The project is comprised of an intricate sequence of photographs, supplemented by an essay on the history of photography in the neighborhood.

_______________________________________________________

From "Concerning Chinatown" by Jason Francisco and Anthony W. Lee

The Making of a Neighborhood

San Francisco’s Chinatown is not today and never was an outpost of China in America, a Chinese city within an American city, as the old stereotype had it. Rather it is a decidedly American place, the site of an immigrant community’s repeated struggles to win the liberty, equality, and well being at the center of the American myth. With the ebbs and flows of its people’s abilities to gain a foothold in San Francisco, Chinatown has witnessed radical changes in its image and influence. It has been reinvented multiple times, by Chinese and non-Chinese alike, but never by having its past disavowed. Its streets are not heavy with time but retain a piebald aspect that augments rather than conceals the depth and dimensionality of communal social experience and immigrant ambition.

The neighborhood is now over one hundred fifty years old. Located at the physical fulcrum of historic San Francisco—between the docks and the wealthy residences of Nob Hill, in the shadow of the financial district—Chinatown first developed as the principal destination for Chinese immigrants during the Gold Rush period. Mostly from the harsh and impoverished countryside of Guangdong province in south China, Chinese men came in search of American dollars to sustain their families back home. As the mines quickly played out, the men took odd jobs in the factories, fisheries, and fields, wandering up and down the state and in the foothills of Nevada in search of a decent job, sometimes any job. But Chinatown always remained a hub where they disembarked upon arrival in California and where they touched base to get supplies or find a warm bunk during their seasonal migrations. The stores, temples, theaters, hotels, and family associations were set up for them. The neighborhood became vital, and although its physical limits remained more or less the same—a ten-block rectangle—the Chinese continually packed its cobblestones and buildings. The men remade the streets and alleys and transformed a haphazard collection of wooden and brick buildings into a quarter of decidedly immigrant use.

During the early period of the city's history, Chinatown also became a defense and an organized response to vigilante violence and legally sanctioned efforts to shape civic ethnic interaction through intimidation and competition. Indeed, the early Chinese experience in San Francisco was marked by vehement anti-Chinese political invective, mob violence, lynching, and legislated segregation. By the latter part of the century, the Chinese experience also included the detention of immigrants on Angel Island in San Francisco Bay, and myriad other sufferings imposed by the Chinese Exclusion Act, in effect from 1882. That Act attempted to put a stopper on Chinese immigration and a stranglehold on the Chinese communities already living in the U.S. Chinatown became, if not a fortress, then something like a compound where the Chinese congregated relatively safely. As the first Exclusion Act was followed up by others in 1892, 1902, 1904, and 1924, Chinatown became the site of an increasingly circumscribed immigrant community.

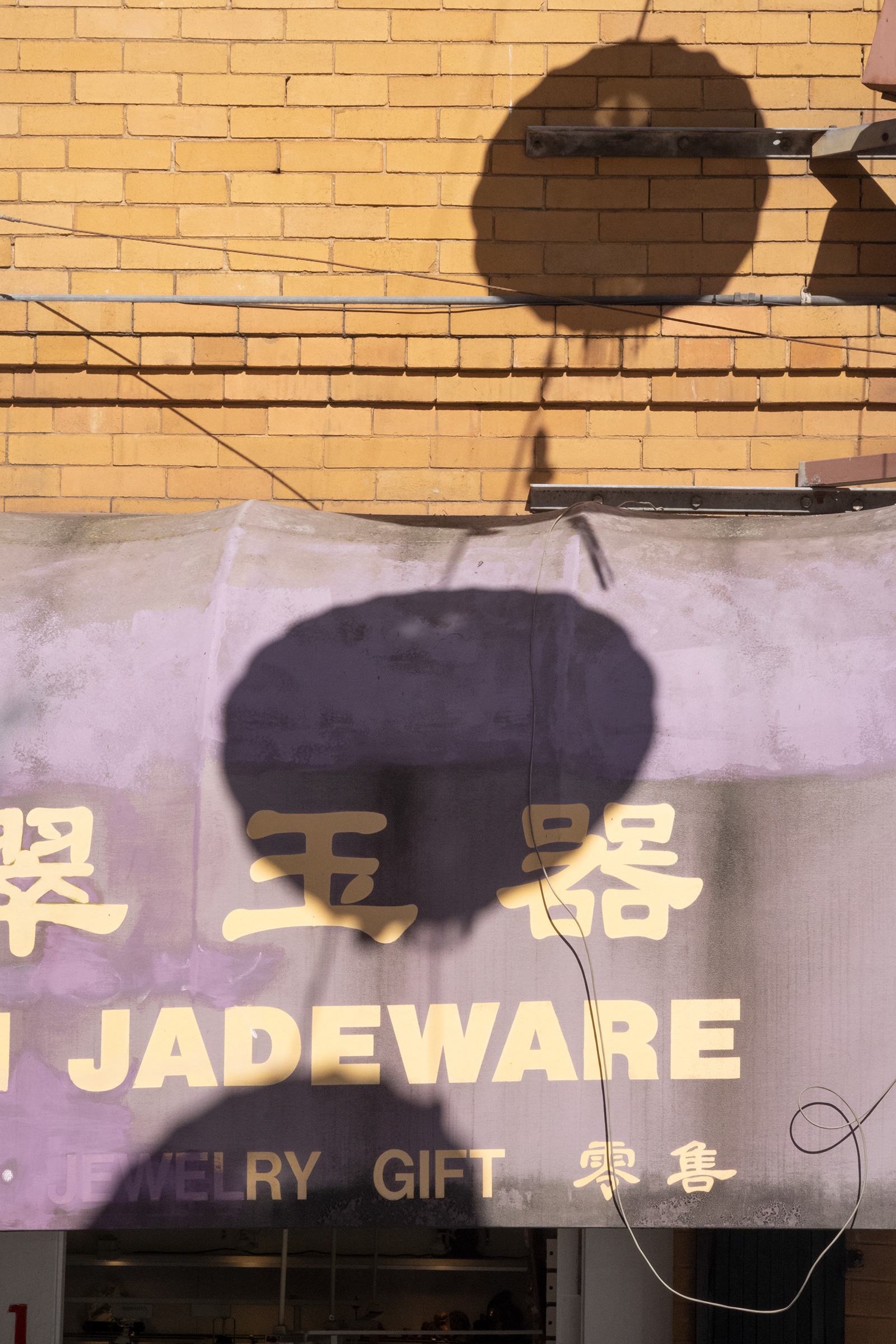

Central to San Francisco’s urban scene since the city’s founding, Chinatown has long been the subject of fascination and fantasy of outsiders. From the 1850s until the great earthquake of 1906, the neighborhood was associated in the non-Chinese civic imagination with much that was considered taboo—stereotypically a place of drug use, prostitution, gang violence, and (particularly regarding laborers) all manner of intemperate, uncultivated behaviors, and in smaller measure a place of ancient wisdom, aesthetic and social refinement (attributed to the merchant classes). After the earthquake, the most ambitious merchants of the neighborhood took steps to capitalize on Chinatown’s grip over the imagination of outsiders. In rebuilding, they accentuated all that had been compelling for the non-Chinese, physically manifest in the construction of sinocized buildings and Chinoiserie decorations, particularly along the commercial corridor of Grant Avenue. The neighborhood retooled itself as tourist destination, a place of tamed exoticism, a site for the staging of the oriental—replete with gift shops, cheap curios, savory meals, and other palatable forms of cultural encounter. If by the middle of the twentieth century an oriental shopping pageant represented Chinatown’s merchants’ strategy for civic promotion, the changing internal social and economic configurations of the neighborhood proved accommodating.

Central to San Francisco’s urban scene since the city’s founding, Chinatown has long been the subject of fascination and fantasy of outsiders. From the 1850s until the great earthquake of 1906, the neighborhood was associated in the non-Chinese civic imagination with much that was considered taboo—stereotypically a place of drug use, prostitution, gang violence, and (particularly regarding laborers) all manner of intemperate, uncultivated behaviors, and in smaller measure a place of ancient wisdom, aesthetic and social refinement (attributed to the merchant classes). After the earthquake, the most ambitious merchants of the neighborhood took steps to capitalize on Chinatown’s grip over the imagination of outsiders. In rebuilding, they accentuated all that had been compelling for the non-Chinese, physically manifest in the construction of sinocized buildings and Chinoiserie decorations, particularly along the commercial corridor of Grant Avenue. The neighborhood retooled itself as tourist destination, a place of tamed exoticism, a site for the staging of the oriental—replete with gift shops, cheap curios, savory meals, and other palatable forms of cultural encounter. If by the middle of the twentieth century an oriental shopping pageant represented Chinatown’s merchants’ strategy for civic promotion, the changing internal social and economic configurations of the neighborhood proved accommodating.

With the repeal of the exclusion acts in 1943 and the Confession Program of the 1950s, the social distortions characteristic of the earlier community slowly eased. Where once the neighborhood was populated by large numbers of bachelor laborers who lived with false identities (assumed to evade the exclusion provisions), after World War II families began to crowd the small apartments and busy sidewalks. After 1947, with the lifting of the city covenant prohibiting persons of Chinese descent from owning property outside of Chinatown, many moved their residences from the neighborhood to escape its cramped accommodations, and to seek a measure of cultural invisibility.

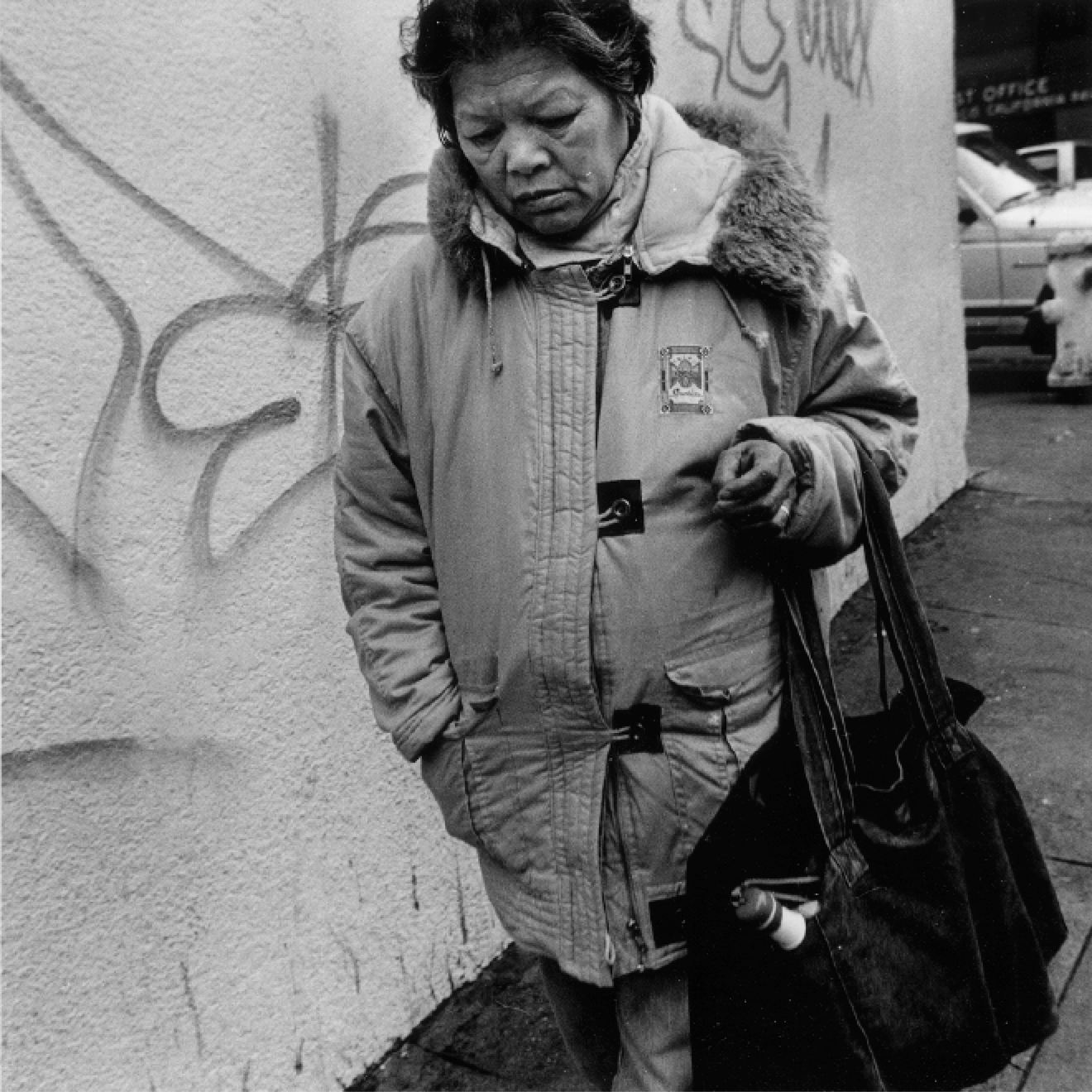

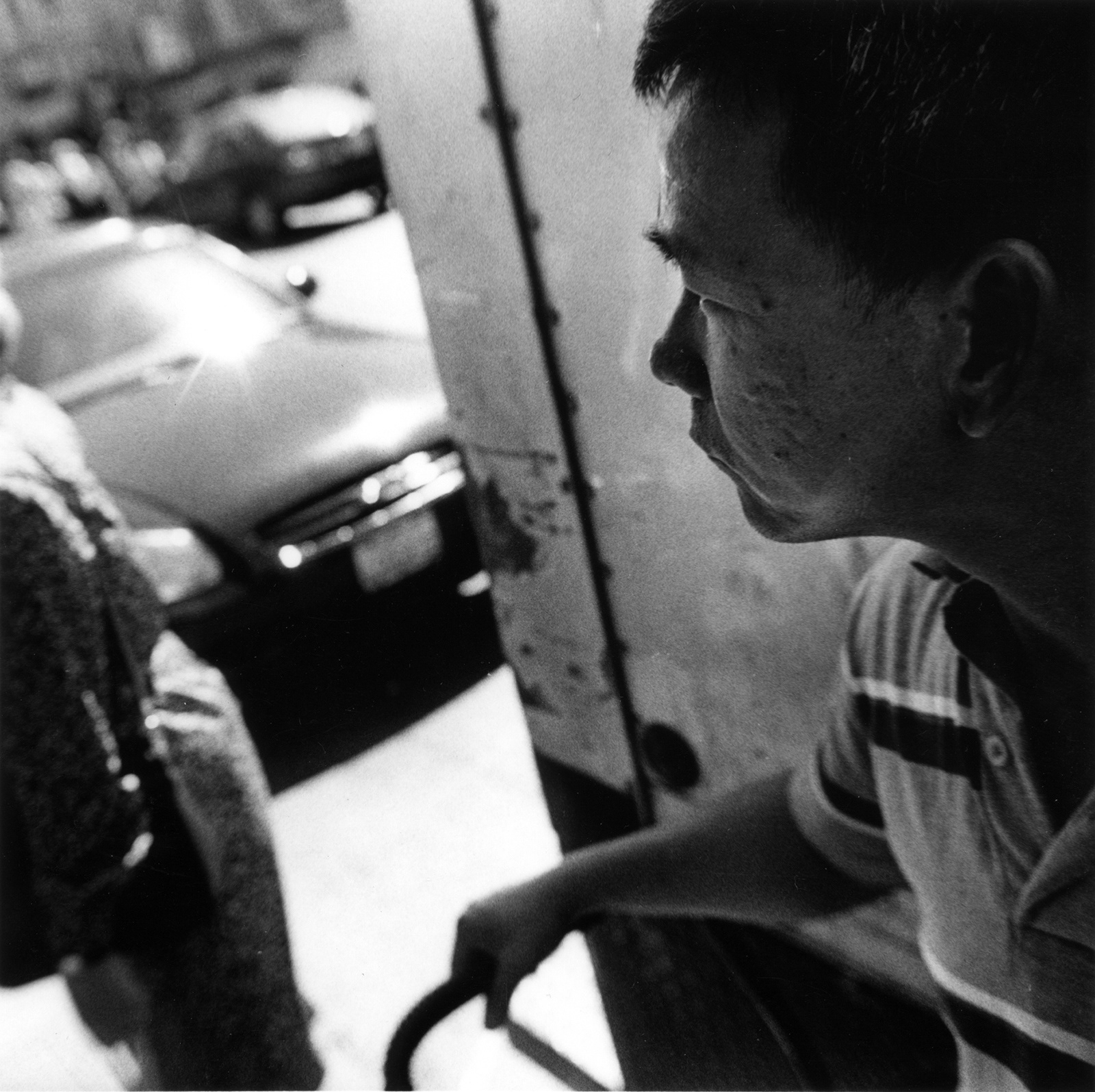

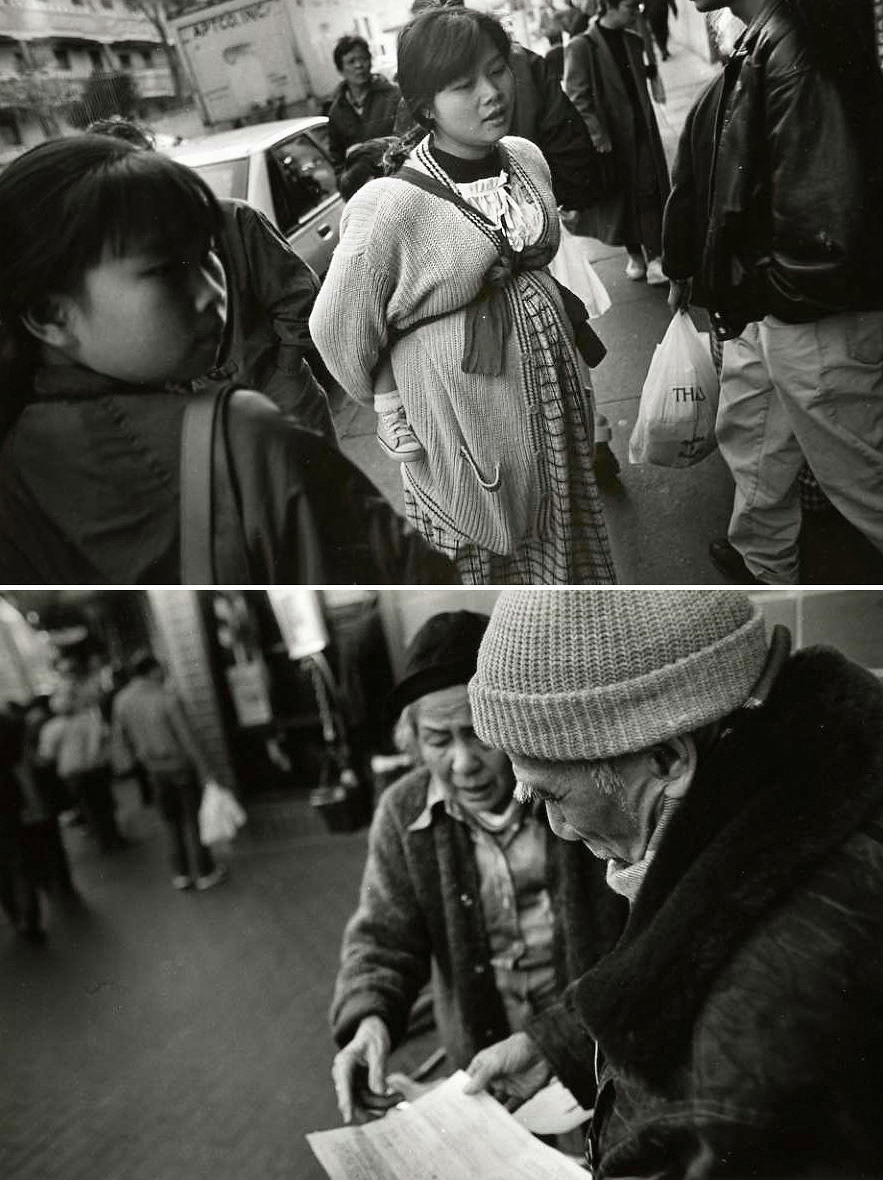

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, Chinatown is an enclave that is neither a ghetto nor merely a rialto. It is a place that is international, multicultural and multilingual. The neighborhood reflects—better than any other location in the San Francisco Bay area—the wide fathom of the Chinese American community's prosperity and its poverty. The neighborhood remains a cultural home for the middle-class Chinese Americans who have long since moved out, but who regularly visit for shopping, dining, New Year festivities and other public events, and who retain their membership in temples and family organizations, and own and operate longstanding businesses—including garment shops and workplaces relying on low-wage labor. The neighborhood also remains the residence of many of the working poor of the Chinese community and other immigrant Asians—those who shop there not just on weekends but everyday, who eat their meals in the inexpensive restaurants, in the backrooms of businesses, who go to school there and spend afternoons in the squares and playgrounds, who linger in conversation on corners, in shops and markets, while shuffling tourists wield maps and cameras. Still one of the most densely populated urban areas in the United States, the neighborhood continues to serve as a refuge and a resource for immigrants and, also, the unassimilated Chinese other of the white American imagination.

Photographs of Chinatown

Photographs of Chinatown

If you were to ask most anyone not living in Chinatown to describe it, the reply might well be organized as a series of verbal images that evoke pictures: steep raking roofs, colorful banners and balconies, rows of fish and fowl lining the outdoor markets, men and women jostling up and down the steep streets, and on and on. Such descriptions are in fact much like the countless snapshots taken in the neighborhood every year—the small prints pasted into albums or put into boxes, the postcards bought and mailed, the jpegs circulated by email and posted to photo-sharing websites. Less a coherent narrative than an sprawling set of impressions—often highly conventionalized—such photographs are partial, fragmented, specific, richly particular and concrete, but also loosely and uncertainly tied to some overall understanding of the neighborhood, if at all. The likeness of outsiders’ images of Chinatown to photographs is—we venture—not accidental. Photographs of Chinatown have been extraordinarily central in forming the non-resident’s imagination. Pictures began to be made almost as soon as the quarter was established. Indeed, one could say that throughout Chinatown’s long history, describing and understanding the neighborhood has been inseparable from acts of making and circulating photographs of it.

This book investigates the history and the implications of photography’s central role in the neighborhood’s multiple identities. Our concern is not merely to repeat, as many others have rightly done, that it is perilous to treat photographs as innocent tidings or as unfiltered evidence of what they show, and just as perilous to reduce them to encrypted ideological messages, plots or stunts. Rather we are interested in how photographs make us readers and viewers in equal measure—readers who discern the biases and contradictions embedded in photographic acts and in the widely varying testimonial roles photographs are given to play over time, and viewers who discern an open field of meanings in the vagaries of photographic purposes and results. No other image-form both shows and tells as synchronistically and as reciprocally as photographs do, depicting as an aspect of saying, and vice versa. It is precisely photography’s interpretive instability that we find a resource in understanding a place such as Chinatown, replete with contradiction and irresolution, and the multiple meanings of visitor and inhabitant, stranger and native.

Our hope is a new kind of book that proposes a dialectics of representation, whose aim is not to capture Chinatown—not to possess it through texts and pictures—but to release Chinatown into a relational image of a demanding and unresolved social experience. Our goal is to place photographs made in Chinatown and texts about Chinatown—photographs both old and new, texts both analytic and testimonial—into overtly searching relations. So doing, we hope to open pathways into the neighborhood’s complex actualities, to allow tensions and differences to emerge between word and text, past and present, outsider and insider, visitor and inhabitant. In effect, we hope to perform through the very structure of the book the neighborhood’s own movements and its hybridity, and so to intimate the ties that bind Chinatown’s inhabitants and its visitors to the imagination of a collective life.

Also see Jason Francisco's essay and experimental filmwork:

And on Jason Francisco’s 2004 exhibition:

Technical notes: As a project now more than thirty years in the making—and still going—this work reflects a diverse technical practice in photography. From 1989-2014, I worked in San Francisco's Chinatown with 35mm cameras (in the beginning a Nikon FM2 and then a Leica R6) mostly fitted with 28mm lenses, sometimes with a close-up filter attached, and Kodak Tri-X. From 1998-2015 I also worked extensively with a Hasselblad 500 C/M, generally with an 80mm Zeiss Planar, both handheld and on a tripod. At first I used Kodak Verichrome Pan and later Ilford FP4+ and other black and white films. From 2015-2021 I worked mostly with a Leica Q and its excellent fixed 28mm lens, and from this year with a Leica SL2-S with various lenses from my collection. Until 2022, all of my work for this project was in black and white; the color photographs were added this year, using the SL2-S with a 1953 Zeiss 135mm f/4 Sonnar, made originally for the Zeiss Ikon Contax rangefinder. —Jason Francisco, 2022