the art of subversion, of revolution, is to probe what counts as established thinking down to its origins, to show how it lacks authority and justice. —pascal, pensées

though i have been politically active since childhood—when my mother had me stuffing envelopes and leafleting for progressive candidates in my native california—i came of age politically in the age of reagan, who was for me (and remains) a low and cynical leader, emblematic of the worst in the american political tradition. i became a war protester in response to reagan’s covert interventions in central america, in which thousands of peasant farmers were terrorized and murdered, and democracy viciously undermined through secret u.s. arms sales to iran. as a young man of draft age, i vowed to myself that i would never die for reagan’s values. publicly resisting wars of american empire seemed imperative.

iraq’s invasion of kuwait in the summer of 1990, when i was 23, sparked the continuous american war that has defined the u.s. hegemon in my adulthood. since 1990 i have actively resisted u.s. militarism, first in the 1991 persian gulf war, and then the continuing “war on terror” initiated after the september 11th, 2001 attacks. these conflicts have inaugurated a “post-vietnam” form of american combat, in which u.s. casualties are kept to a politically desirable low, while foreign casualties are censored and concealed: american deaths in u.s.-led wars since 1991 number fewer than 6000, while estimates of iraqi and afghani deaths range from 100,000 to over 1 million. casualty rates are similarly disproportionate. in the prison camps at guantánamo bay and bagram air force base, and in a network of secret prisons and black military sites around the world, the u.s. currently detains thousands of so-called enemy combatants without charge, including children, and tortures an untold number with impunity. it seems to me that it is only an accident of birth that we ourselves are not the targets or the “collateral damage” of the american war machine of our time. compounding the moral obscenities of u.s. wars in the last two decades is the fact that the conflicts have enormously profited oil conglomerates, multinational banks, arms dealers and engineering corporations—to the point that it is difficult not to conclude that the u.s. military has essentially become a force for hire in the securing of their interests.

i have often asked myself: what image can compass the tragedy of these wars, and at the same time how little the idea of “tragedy” actually recuperates? hollywood portrayals of american wars since vietnam focus on the hell of the soldier’s experience, using fictionalized realism to generate a sympathetic identification with soldiers’ suffering, while skirting the larger ethical and political issues in which soldiers’ trauma is implicated. there are no major motion pictures about war resistance or war resistors. there are no great actors portraying citizen-soldiers who struggle nonviolently for peace—the millions of americans who participate in meetings, protests, marches and vigils, from small groups on college campuses to the hundreds of thousands who periodically claim the downtowns of the largest u.s. cities. mainstream photojournalism likewise offers no sustained depiction of the americans who with fierce and loving dissent reject the charade of patriotism, loyalty to country, and the conceits of american nationalism.

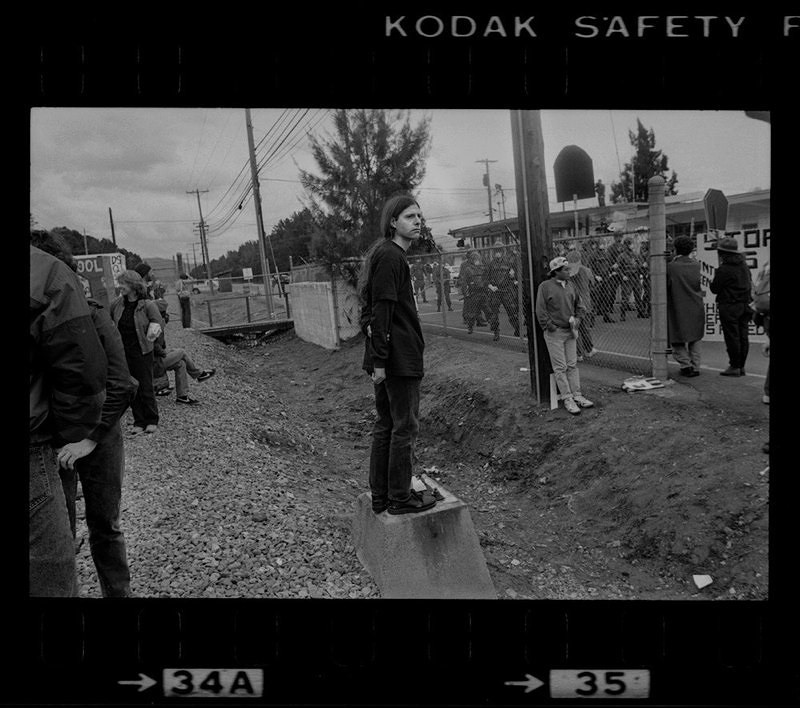

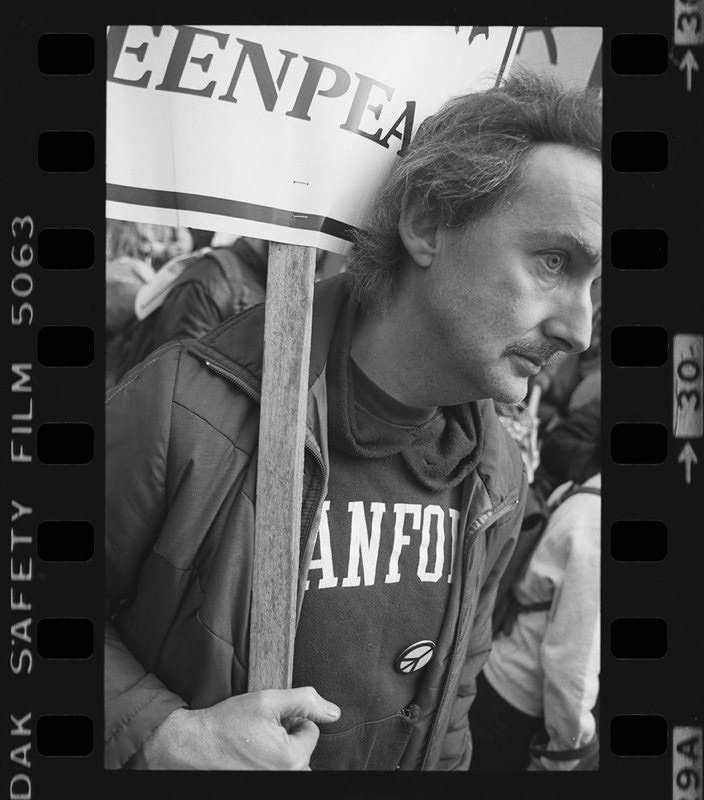

the photographs here, a handful of thousands made while i protested in san francisco, oakland, washington, d.c., philadelphia and new york between 1991 and 2009, attempt to describe the best that the people themselves have offered in the face of the u.s. government’s ill judgment and its crimes: a demand for sanity uttered from inside the belly of the world’s rogue superpower. i photographed as a way of looking for—and affirming when i found it—what it is openly to be a citizen of conscience, and what it is publicly to build a citizenry of conscience. no doubt the tasks of public citizenship are difficult and sometimes mercurial, and i see in my pictures both great moral determination and the weight of its demands. if i have succeeded with these pictures, they will release something of the powerfully unfinished camaraderie that arises when like-minded strangers join together in the public sphere, and collective purposes become both inwardly magnified and palpably larger than each person. i will have succeeded if the photographs stir an awareness of what courageous men and women can accomplish in the subversive art of pursuing justice when it counts.

jason francisco

atlanta, march 2010