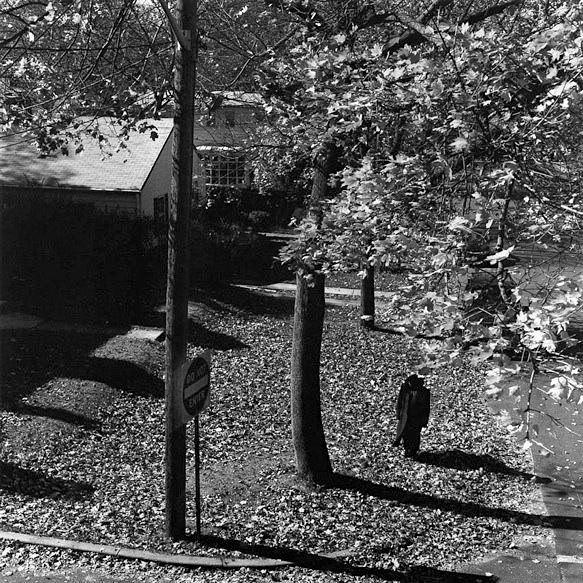

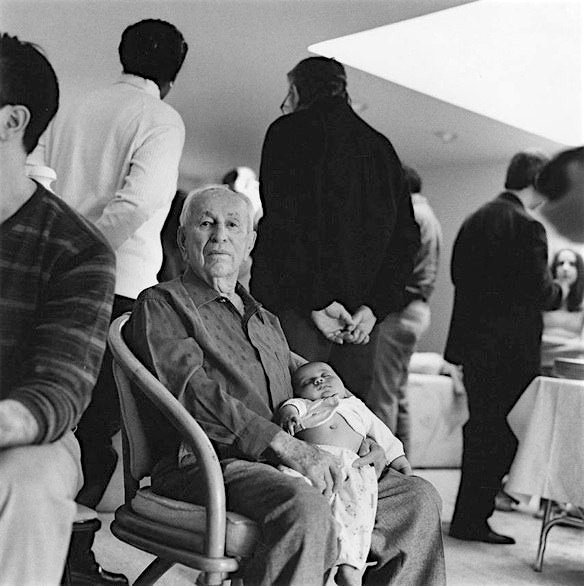

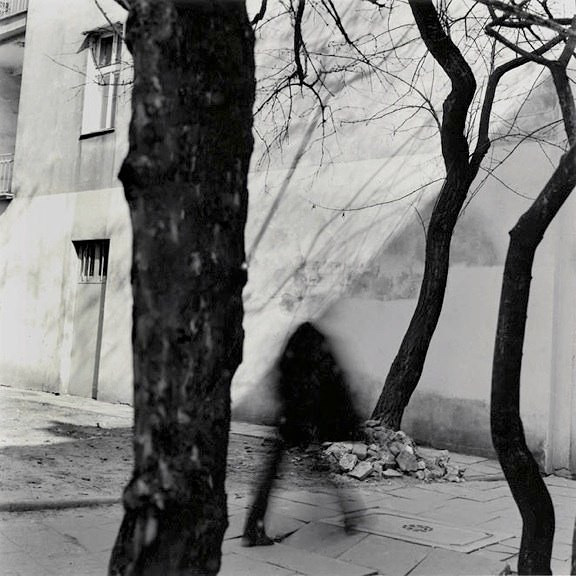

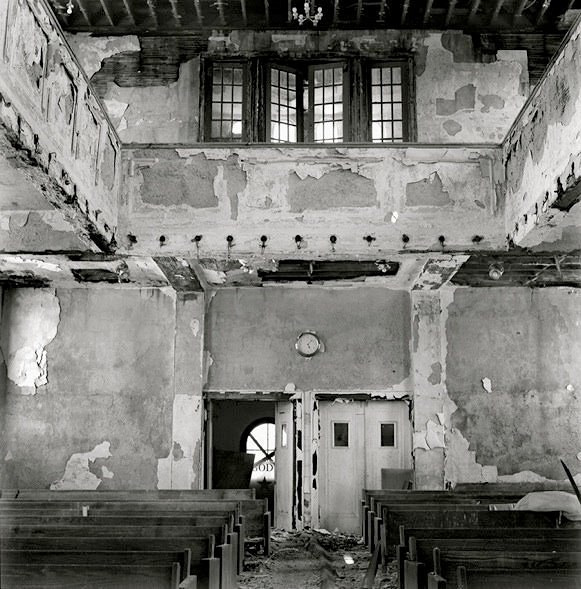

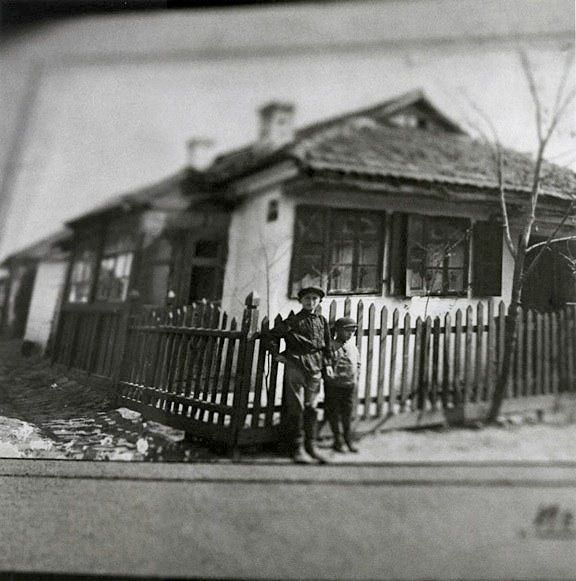

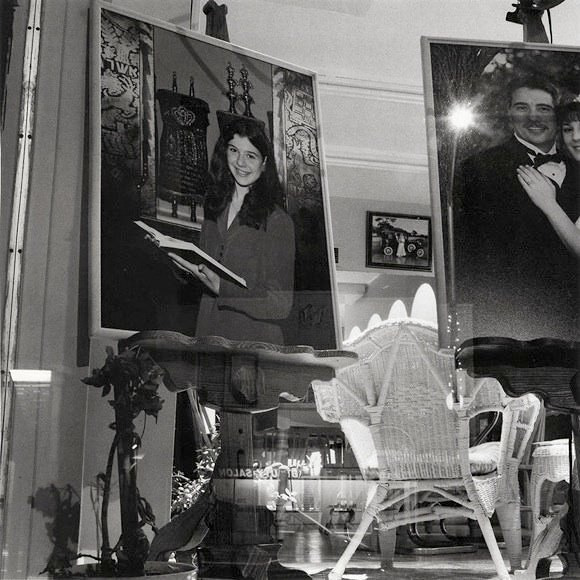

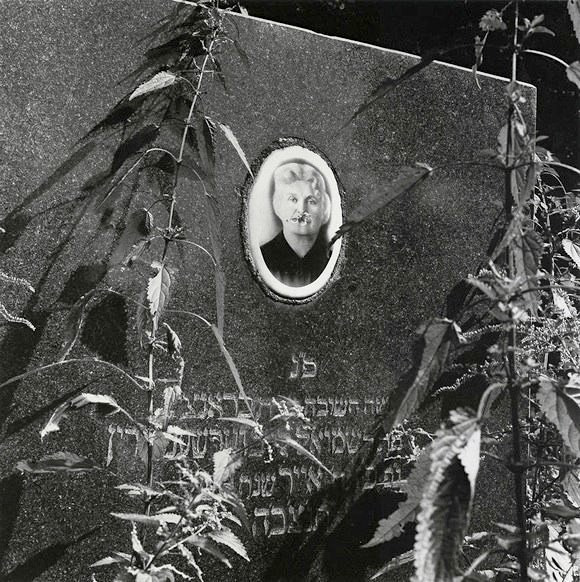

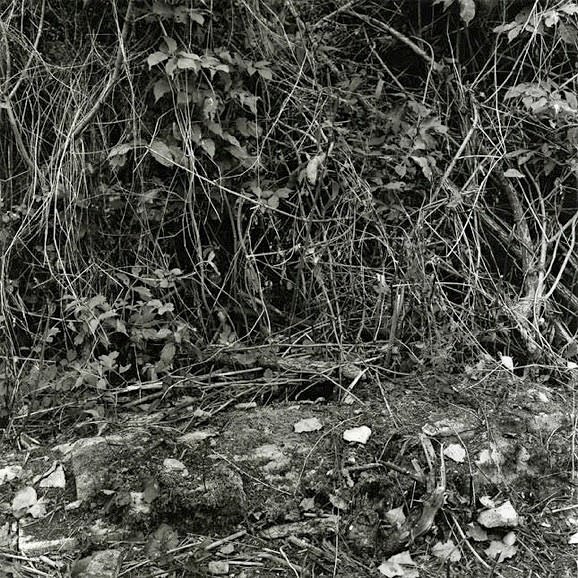

Far from Zion: Jews, Diaspora, Memory (Stanford University Press, 2006) uses the photo-text form to explore the inheritances of Ashkenazic Jewish history in Europe and North America in the last century. In the spirit of unsentimental reckoning, the book wrestles with the contradictory inheritances of the last century of Jewish experience, in which the historic themes of migration, assimilation and destruction have assumed particularly concentrated and ruthless forms. As a visualization of diaspora—dispersedness, scatteredness, loss—the book testifies by means of silence and absence, using a medium traditionally aligned with confirmative and expository attitudes toward knowledge and understanding.

What follows is the beginning of the essay that concludes the photographic sequence in Far from Zion.

Diasporic Investigations

1. Two propositions:

Diaspora: a name for Jewish culture in its contingency and its conditionality.

Diaspora: a name for decertified Jewish meaningness as it abides within Jewish culture.

2. A diasporic investigation cannot be geographic, historical, literary, philosophic or autobiographical alone, but must be—like diaspora itself—heterogeneous and hybrid.

3. How much does “now” encompass? How far back do we measure “now”?

4. The passing century: a distillation of 2000 years and more of Jewish diaspora.

A century: in which the leading themes of Jewish diasporic life—migration, assimilation, destruction—have assumed particularly concentrated and ruthless forms.

5. The incunabulum of diaspora—dispersion, dispersedness—is, at one level, very remote: dating from the first development of permanent Jewish communities outside of Palestine in ancient Mesopotamia after the fall of Jerusalem in 587 B.C.E., and later the growth of Jewish communities across the Hellenistic-Roman world during the period of the Second Temple, and still later the large Jewish migrations from Roman-controlled Palestine following the suppression of Jewish revolts in 70 C.E. and 135 C.E.

By the 5th century C.E. Jews had become almost entirely a diaspora people.

6. If Jewish history speaks in the present tense—the tense in which texts speak—the Jewish present speaks in the future tense, the tense of possibility.

7. The biblical narrative tells us: Jacob, the thiever and the maker of blessings, grips “beings divine and human” for a long night and brings them to the brink of dawn, of light—and so “prevails” and wins the new name, Israel, godwrestler.

I wonder: not whether every Jew has an eponymous ancestor situated on the brink of an enigmatic strength, but how diasporic lifeways likewise steal and wrestle and win new names without discrediting the old.

8. The Torah further tells us that the Jews become a people in a process of journeying: released from tyranny and servitude in Egypt, the people enter the wilderness, where isolation, precarious physical subsistence and the contradiction of a seemingly destinationless pilgrimage rupture them from their origins. Within the structure of the text itself, the exodus into the wilderness is tethered to a narrative trope of displacement redeemed, which is in effect the collective elaboration of Abraham’s example—Abraham who leaves his native place on god’s insistence, accepting severance from home as a form of divine guidance. But as I read it, the trope of displacement redeemed is bound up with another trope: the inscrutability of this redemption as it is happening. The text does not blithely reclaim Abraham’s wandering—make destiny from destination—but is at pains to do so. Likewise it labors to mitigate the decades of wandering in the Sinai wilderness, a place the biblical translator, Everett Fox calls “the site of liminality par excellance.” In the revelation at Sinai, the text attempts to reclaim both the rupture of the liberation and the peril of the attendant journeying by recasting the place of the liminal as the place of god’s presence, from which certainty, covenant and perpetuity arise. And how convincingly? If the reclamation might be put in the form of a homiletic question—how do tribulations teach trust in god?—an answer depends on the continued presence of the aporia itself, the capacity of the text not to discredit the condition of sustained loss. In effect, an enduring collective salvation must harbor a dangerous possibility—the perpetual inability to distinguish liberation from catastrophe, freedom from ruin.

9. My friend, Jeff Fort points me to an insight of Maurice Blanchot: it is an exodus (literally a “journey-out”) that brings the Jewish people into existence (literally a “standing apart”).

10. In the Jewish imagination, mythopoetic origins go by the name of the historical.

11. From my notebooks, December 1998, Paris:

the work that “diaspora” might be made to do: organizing the dimensions of loss that persist within jewish affirmations, opening pathways into the non-intact Jewishness around and within us, and so approaching the place within which Jewish life mostly dwells: the middle condition between rootedness and uprootedness, placement and displacement, origin and destiny.

12. From my notebooks, June 1998, San Francisco, California:

what would it be to make a work that responds sedulously to the discontinuities and fractures that yield “the jewish” in the passing jewish century? what would it be to make pictures directed toward the disarticulated realities of jewish life—that approach the contemporary jewish diaspora not as an ethnography of fixed, recordable places, but an archaeology of places, objects and persons that might signal the crisis of origin inscribed within various local originations of the jewish? what would it be to make a work that searches out the apartness of jewish experience from presumed legibility, and from notions of stable lifeways in intact homelands?

13. H. Leivick:

—Who told you to rebuild the ruins?/ Once ruined, it should remain ruined.

14. The better part of remembering is blotting—in both the sense of soaking and covering—supposition.

15. There are two questions that sometimes change places: “what are you?” and “who are you?”

“What are you?” asks for a name or a predicate, such as, in my case, “a Jew,” or “a photographer.” “Who are you?” asks for a deflection of such statements, a resistance to their authority, an easing away from their gravity.

* * *