The small town of Bełżec sits today in the far southeastern corner of Poland, ten miles from the Polish-Ukrainian border, and before the war was located in the center of Poland, at the midpoint of the historical province of Galicia, on the main rail line connecting Lviv (Lwów, Lvov, Lemberg) and Lublin. At the start of the Second World War in 1939, the town fell in the German zone of occupation, according to the Hitler-Stalin pact, and in April 1940, a labor camp using Jewish prisoners was established to dig anti-tank trenches. In November 1941, five months after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, work began to transform the site of the Bełżec labor camp into a factory for mass murder using stationary gas chambers. This work was undertaken prior to the famous Wannsee Conference of January 20, 1942, where plans for the complete physical annihilation of Jews under German control was presented to the top tier of Nazi leadership, under the code name Operation Reinhard. By February 1942, the death camp was finished, a square plot encompassing 18 acres, situated directly beside the main railway line.

Daily gassing operations began at Bełżec on March 17, 1942, and ceased on December 11, 1942––39 weeks and two days. The death camp’s history can be divided into two periods. In its first four months, the gassing occurred in comparatively smaller wooden chambers which did not function as planned. Some 80,000 people were murdered during this period. In its final five months, gassing took place in larger brick chambers, and killed at least 355,000 people in five months. The corpses were buried in mass graves in the camp itself. Altogether, an estimated 450,000-600,000 Jews were murdered at the camp, plus an undetermined number of Roma and Polish political prisoners, probably in the tens of thousands. Most of the camp’s victims came from southern and southeastern Poland, and the camp was the primary killing site of the Jews of Galicia. Other Jews were transported from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia. The camp had two known survivors, only one of whom was able to provide an account of his experiences.

After the camp’s closure, the German high command ordered that it be razed and thoroughly demolished. The bodies in its mass graves were exhumed and burned on large grills made of railroad track, the remaining bone fragments pulverized by special machines, and the ashes scattered over the site. It was replanted and converted into a fake farm, which is what the Soviet Army found at liberation in 1944. The careful demolition of the site combined with the extreme paucity of survivor testimony combined to make it much less well known than other major Nazi killing centers.

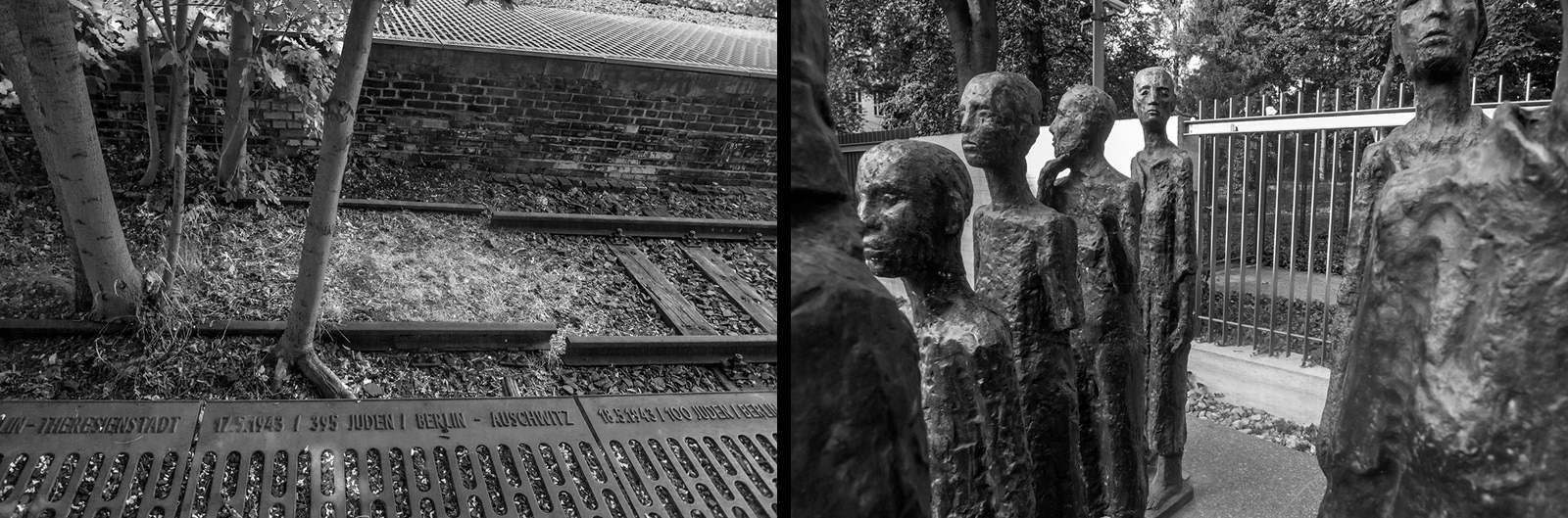

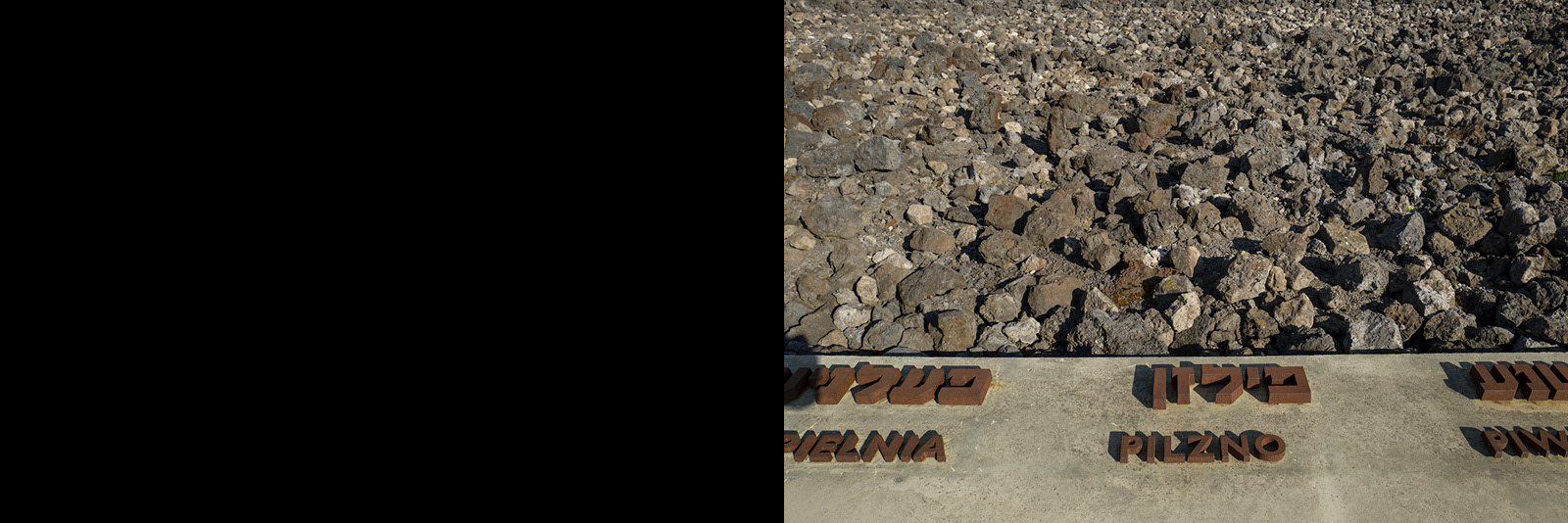

The site lay forsaken and largely forgotten until the late 1990s, when extensive archaeological studies began. In 2004, the site became a branch of the Majdanek State Museum, and in 2005 a new monument was dedicated at Bełżec, together with the opening of a small, very high quality museum. The monument covers the entirety of the camp’s footprint. A field of crushed boulders was installed over the site, its colors changing subtly to mark the locations of the mass graves. A cement walkway follows the camp’s contour, with each deportation to the camp commemorated in chronological order, in cast iron letters spelling the name of place of origin in Yiddish and Polish, along with the date of the train’s arrival. A walkway leads through the center of the camp to its far end, where the gas chambers once stood, to two long memorial walls, whose bases are situated some thirty feet below the surface of the earth.

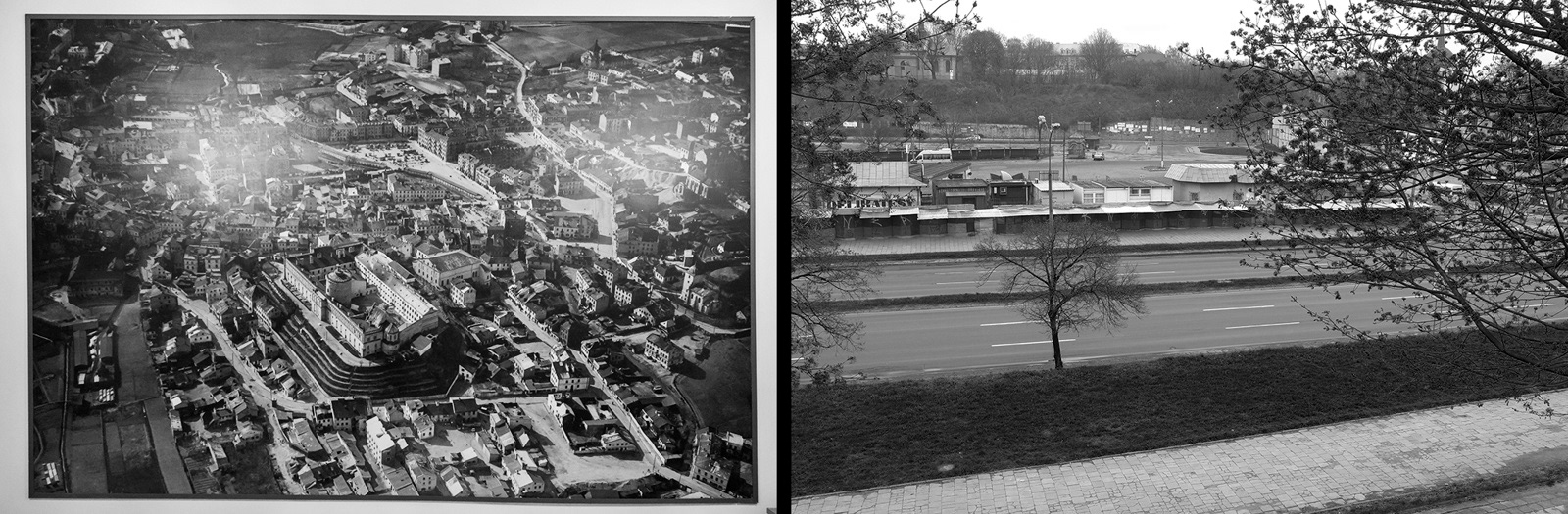

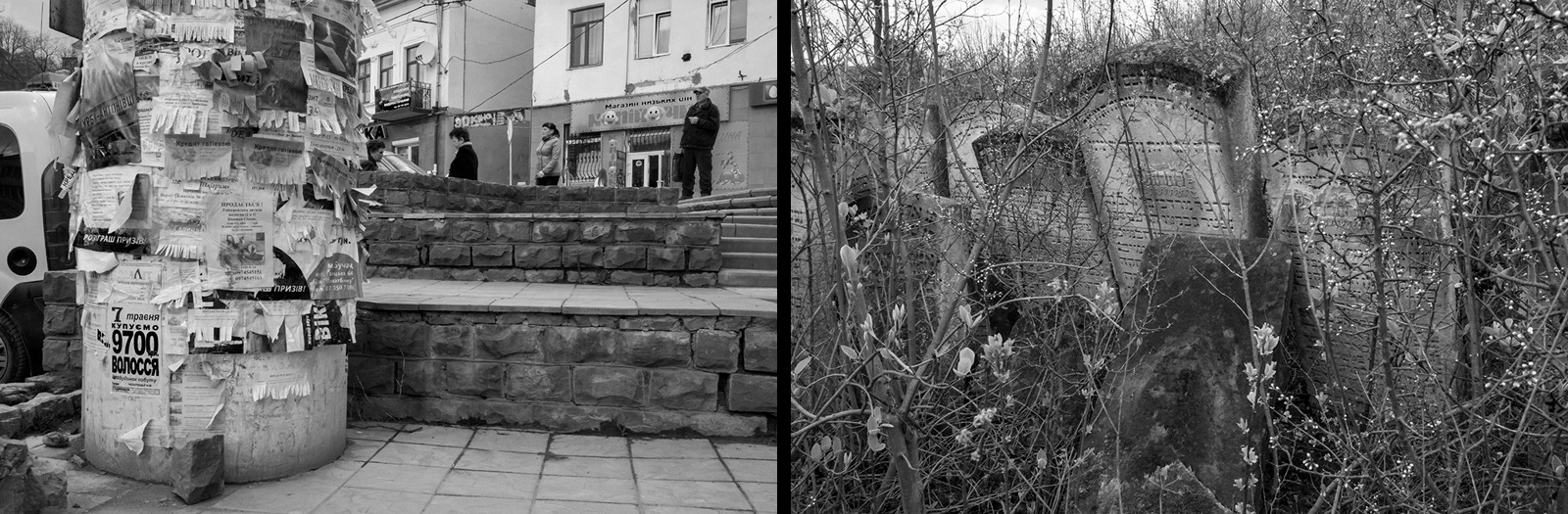

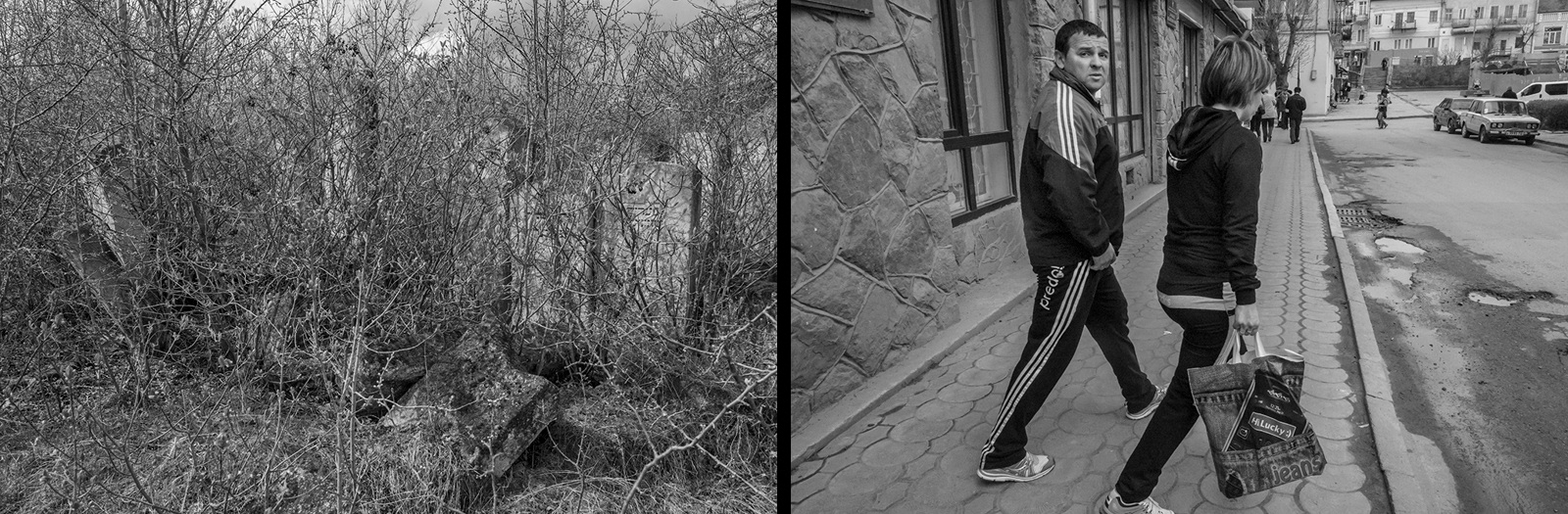

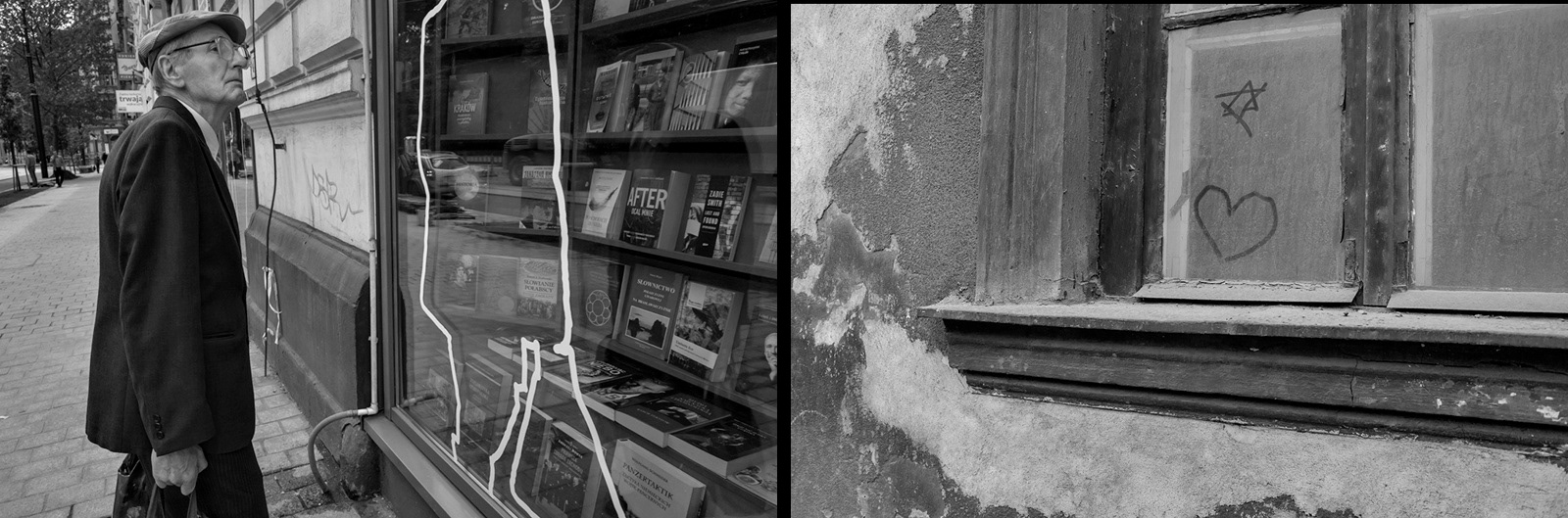

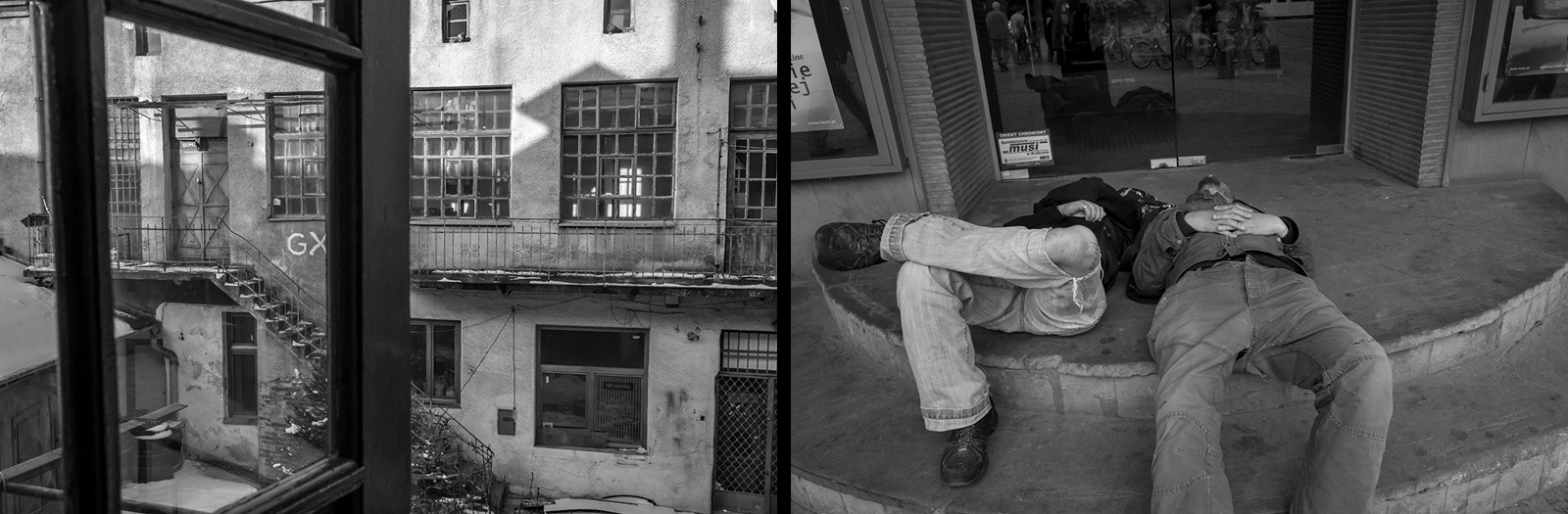

The site is profoundly difficult to fathom––emotionally, intellectually, spiritually, in every way. The photographs here represent one small effort to receive its enormity. In my most recent visit to the site in the summer of 2015, I walked the camp’s perimeter slowly, reading the names at my feet aloud. Many of the towns, cities, and villages were places I knew firsthand, having traveled and photographed extensively in east-central Europe in recent years. I was struck with a simple idea: to connect the image of contemporary Bełżec to contemporary images of the places from which its victims came. The sequences here attempt just such a connection, not of all the 276 places from which Jews were deported to Bełżec, but a portion of them, 72 to be exact. These 72 places, currently in Poland, Ukraine, Austria and Germany, are as follows:

Berezhany, Berlin, Bibrka, Bobowa, Bochnia, Bolekhiv, Borislav, Brody, Buchach, Burshtyn, Chortkiv, Cieszanów, Dąbrowa Tarnowska, Dolina, Drohobych, Dukla, Działoszyce, Gorlice, Hvizdets, Ivano-Frankivsk, Izbica, Jarosław, Jawornik Polski, Kalush, Kraków, Khodoriv, Kolomiya, Komarów, Kosiv, Kraśnik, Kuty, Łancut, Łaszczów, Lesko, Lubaczów, Lublin, Lubycza Królewska, Lviv, Mielec, Modliborzyce, Munich, Myślenice, Narol, Olesko, Peremyshliyani, Pidhaitsi, Pilzno, Przemyśl, Rava Ruska, Rohatyn, Rymanów, Sambir, Sniatyn, Stary Sambir, Stryi, Stuttgart, Szczebrzeszyn, Sokal, Tarnogród, Tarnów, Ternopil, Tomaszów Lubelski, Uhniv, Velyki Mosty, Vienna, Wielkie Oczy, Zabolotiv, Zamość, Zasław, Zhovkva, Zhydachiv, Zwierzyniec

The list of towns on the perimeter walk at Bełżec is, like this list, alphabetical. In the alphabetic listing I see an intelligent curatorial decision on the part of the Bełżec museum authority: to register the geography of the Holocaust as a catastrophic simultaneity, a great ingathering of rupture without a narrative apparatus to modulate our reception of the crime––no ranking, no hierarchy, but the fact of annihilation that equally penetrated Jewish communities large and small, provincial and cosmopolitan, famous and obscure. It is not only this sense of co-occurrence that makes the memorial so impactful. Even more importantly, the perimeter walk of Bełżec forces the visitor constantly to receive the names in the foil of the blackened, stony terrain now covering the camp site itself––a terrain recalling images of distant, harsh planets on which no human being has ever walked, an alien and inert world of loss, meaninglessness, nothingness.

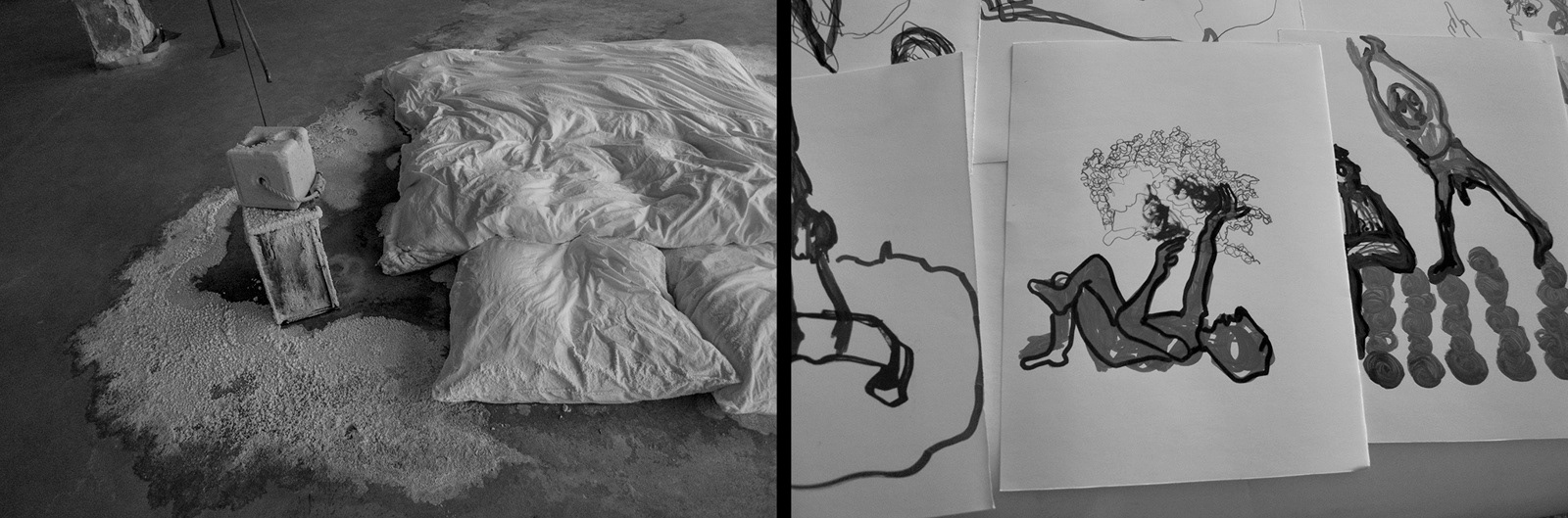

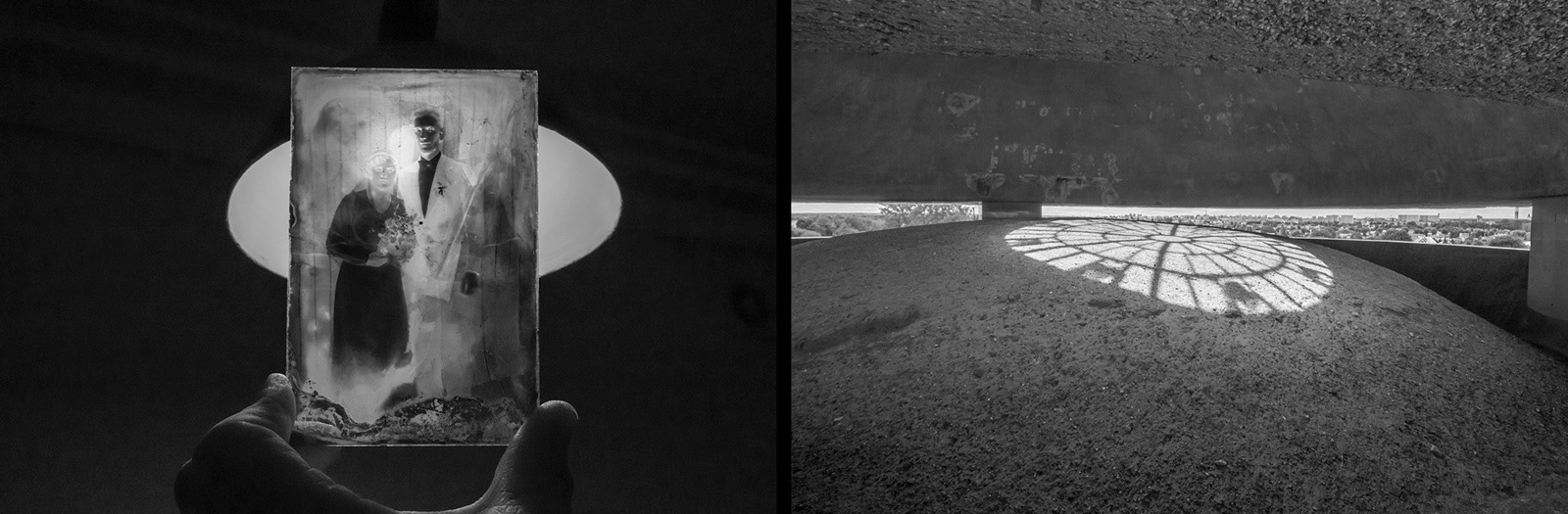

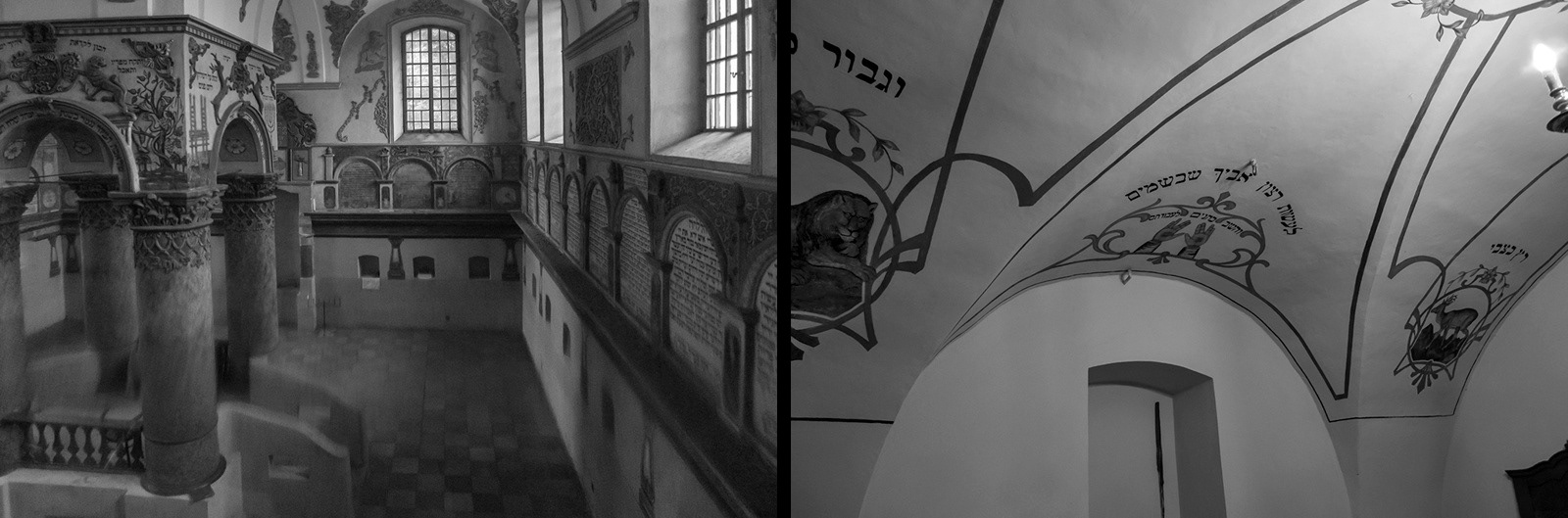

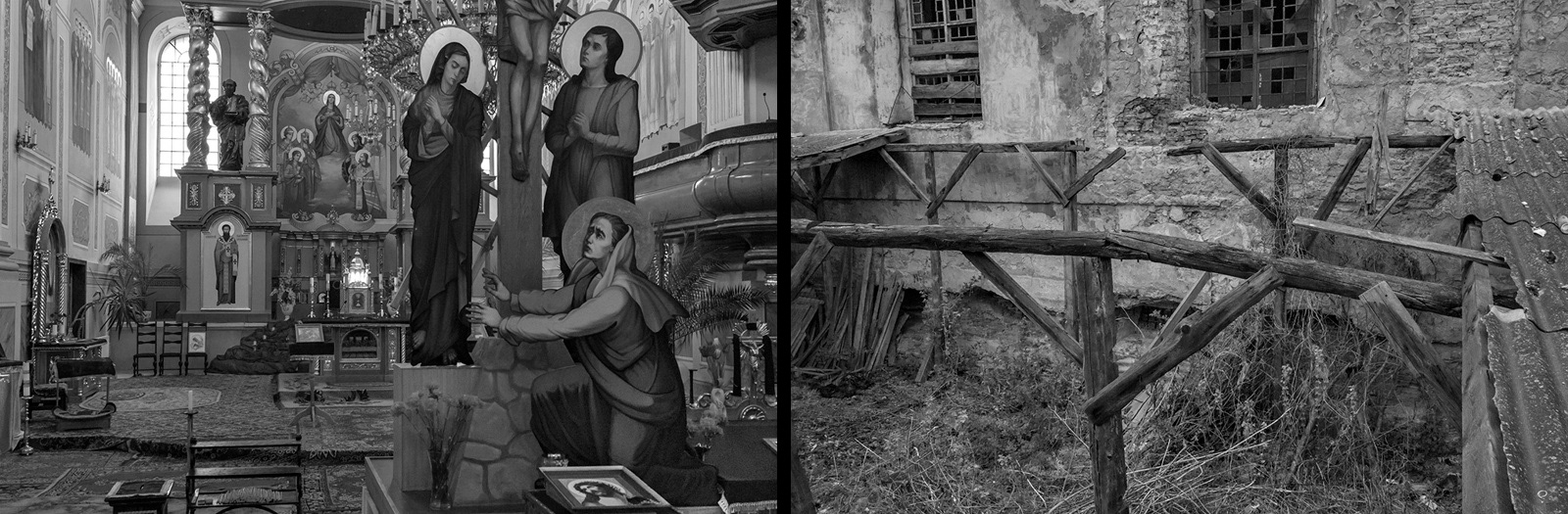

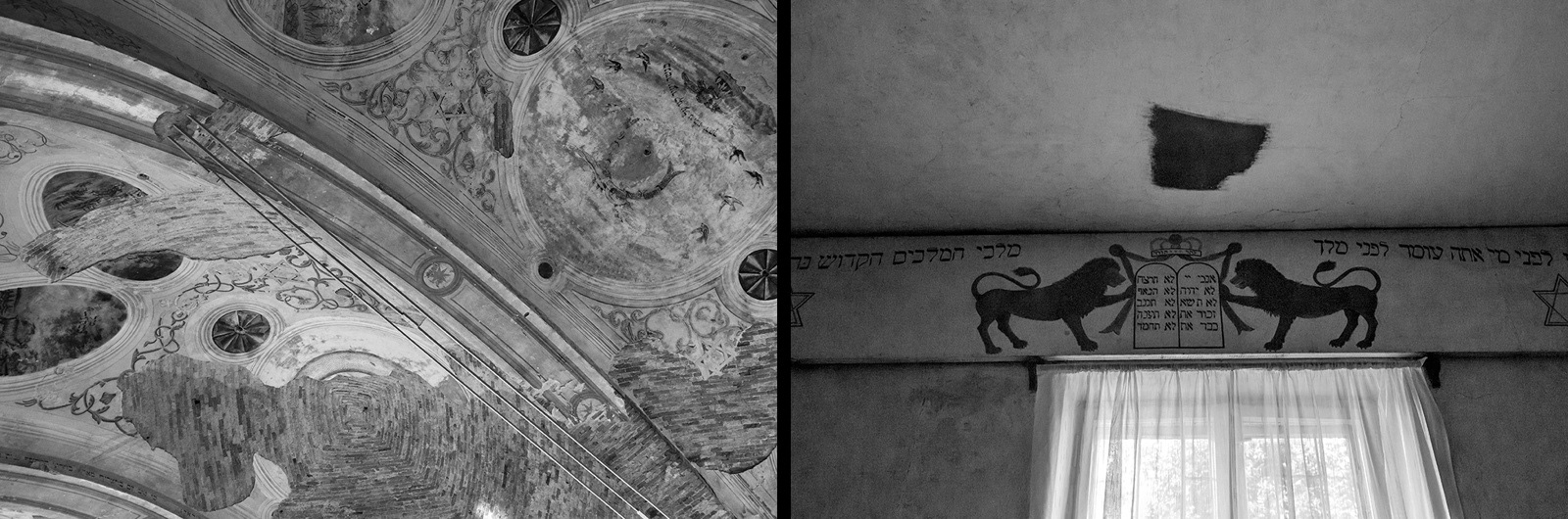

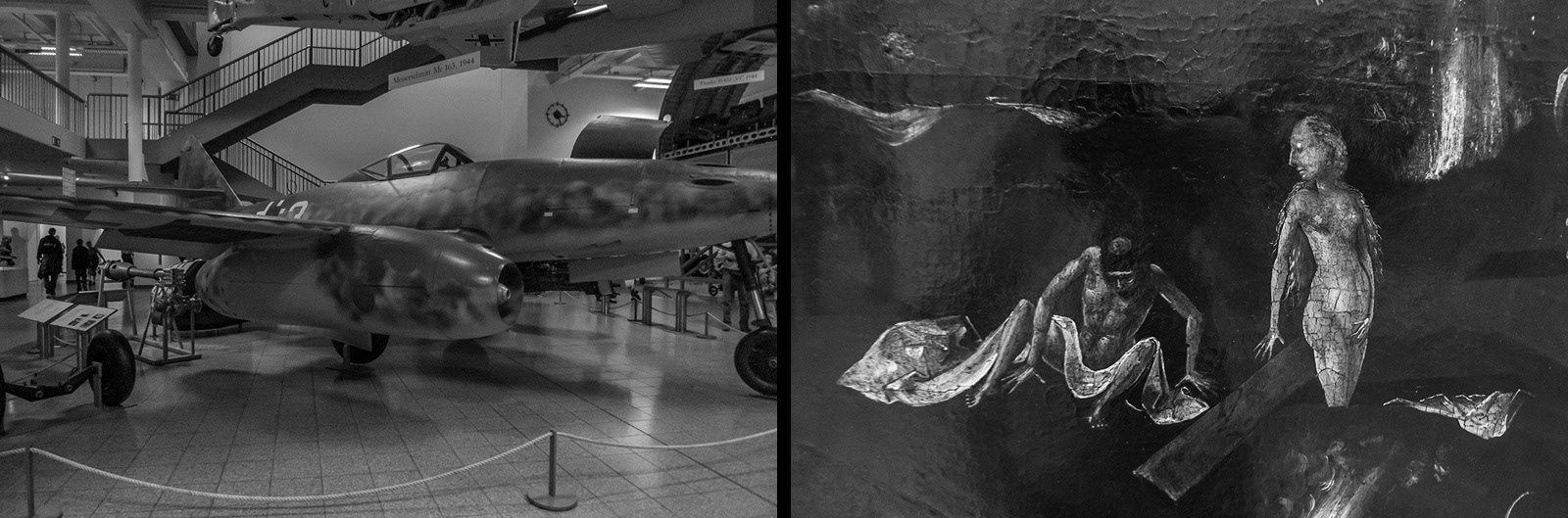

The photographic sequences here force the boulder fields of Bełżec into a return to the geography to which the site continuously refers. I do not know whether it would be better to say it is a linking of loss with loss, or trace with trace. Trace and the loss of trace are not clearly distinguishable in the geography of genocide. And the re-linking does not stand to reveal new information or new knowledge, insights into causes or lessons. The black and white pictures confess little to nothing about Bełżec itself, though they often address the many important local dimensions of the Holocaust, as if to draw the crimes of Bełżec back to the site of myriad other genocidal crimes dispersed across the countryside.

Or to put the point differently, just as contemporary Bełżec testifies at once directly and obliquely to what happened there, so too the pictures here point directly and obliquely to Jewish absence. Absence, of course, cannot be shown directly. Perhaps the most a photographer can do is make pictures that solicit an imagination from within themselves, and then enter them into new combinations––in this case, diptychs and sequences of diptychs––toward a sense of things not made visible in the pictures but suggested, inferred and conjured by them. When observational photographs are made to do conceptual work, a visual ontology of absence takes shape, quite distinct from the commonplace ontology of presence that characterizes our approach to photographs.

So the sequences here represent an open inquiry into the losses that the genocide has left us, the inheritors. These losses paradoxically continue to grow and continue to die. They can perhaps be poked into partial, dim recognition, but they cannot really be fathomed, just as they cannot be eclipsed.

Jason Francsico

Atlanta, October 2015

After the camp’s closure, the German high command ordered that it be razed and thoroughly demolished. The bodies in its mass graves were exhumed and burned on large grills made of railroad track, the remaining bone fragments pulverized by special machines, and the ashes scattered over the site. It was replanted and converted into a fake farm, which is what the Soviet Army found at liberation in 1944. The careful demolition of the site combined with the extreme paucity of survivor testimony combined to make it much less well known than other major Nazi killing centers.

The site lay forsaken and largely forgotten until the late 1990s, when extensive archaeological studies began. In 2004, the site became a branch of the Majdanek State Museum, and in 2005 a new monument was dedicated at Bełżec, together with the opening of a small, very high quality museum. The monument covers the entirety of the camp’s footprint. A field of crushed boulders was installed over the site, its colors changing subtly to mark the locations of the mass graves. A cement walkway follows the camp’s contour, with each deportation to the camp commemorated in chronological order, in cast iron letters spelling the name of place of origin in Yiddish and Polish, along with the date of the train’s arrival. A walkway leads through the center of the camp to its far end, where the gas chambers once stood, to two long memorial walls, whose bases are situated some thirty feet below the surface of the earth.

The site is profoundly difficult to fathom––emotionally, intellectually, spiritually, in every way. The photographs here represent one small effort to receive its enormity. In my most recent visit to the site in the summer of 2015, I walked the camp’s perimeter slowly, reading the names at my feet aloud. Many of the towns, cities, and villages were places I knew firsthand, having traveled and photographed extensively in east-central Europe in recent years. I was struck with a simple idea: to connect the image of contemporary Bełżec to contemporary images of the places from which its victims came. The sequences here attempt just such a connection, not of all the 276 places from which Jews were deported to Bełżec, but a portion of them, 72 to be exact. These 72 places, currently in Poland, Ukraine, Austria and Germany, are as follows:

Berezhany, Berlin, Bibrka, Bobowa, Bochnia, Bolekhiv, Borislav, Brody, Buchach, Burshtyn, Chortkiv, Cieszanów, Dąbrowa Tarnowska, Dolina, Drohobych, Dukla, Działoszyce, Gorlice, Hvizdets, Ivano-Frankivsk, Izbica, Jarosław, Jawornik Polski, Kalush, Kraków, Khodoriv, Kolomiya, Komarów, Kosiv, Kraśnik, Kuty, Łancut, Łaszczów, Lesko, Lubaczów, Lublin, Lubycza Królewska, Lviv, Mielec, Modliborzyce, Munich, Myślenice, Narol, Olesko, Peremyshliyani, Pidhaitsi, Pilzno, Przemyśl, Rava Ruska, Rohatyn, Rymanów, Sambir, Sniatyn, Stary Sambir, Stryi, Stuttgart, Szczebrzeszyn, Sokal, Tarnogród, Tarnów, Ternopil, Tomaszów Lubelski, Uhniv, Velyki Mosty, Vienna, Wielkie Oczy, Zabolotiv, Zamość, Zasław, Zhovkva, Zhydachiv, Zwierzyniec

The list of towns on the perimeter walk at Bełżec is, like this list, alphabetical. In the alphabetic listing I see an intelligent curatorial decision on the part of the Bełżec museum authority: to register the geography of the Holocaust as a catastrophic simultaneity, a great ingathering of rupture without a narrative apparatus to modulate our reception of the crime––no ranking, no hierarchy, but the fact of annihilation that equally penetrated Jewish communities large and small, provincial and cosmopolitan, famous and obscure. It is not only this sense of co-occurrence that makes the memorial so impactful. Even more importantly, the perimeter walk of Bełżec forces the visitor constantly to receive the names in the foil of the blackened, stony terrain now covering the camp site itself––a terrain recalling images of distant, harsh planets on which no human being has ever walked, an alien and inert world of loss, meaninglessness, nothingness.

The photographic sequences here force the boulder fields of Bełżec into a return to the geography to which the site continuously refers. I do not know whether it would be better to say it is a linking of loss with loss, or trace with trace. Trace and the loss of trace are not clearly distinguishable in the geography of genocide. And the re-linking does not stand to reveal new information or new knowledge, insights into causes or lessons. The black and white pictures confess little to nothing about Bełżec itself, though they often address the many important local dimensions of the Holocaust, as if to draw the crimes of Bełżec back to the site of myriad other genocidal crimes dispersed across the countryside.

Or to put the point differently, just as contemporary Bełżec testifies at once directly and obliquely to what happened there, so too the pictures here point directly and obliquely to Jewish absence. Absence, of course, cannot be shown directly. Perhaps the most a photographer can do is make pictures that solicit an imagination from within themselves, and then enter them into new combinations––in this case, diptychs and sequences of diptychs––toward a sense of things not made visible in the pictures but suggested, inferred and conjured by them. When observational photographs are made to do conceptual work, a visual ontology of absence takes shape, quite distinct from the commonplace ontology of presence that characterizes our approach to photographs.

So the sequences here represent an open inquiry into the losses that the genocide has left us, the inheritors. These losses paradoxically continue to grow and continue to die. They can perhaps be poked into partial, dim recognition, but they cannot really be fathomed, just as they cannot be eclipsed.

Jason Francsico

Atlanta, October 2015

Note / October 2024: It is now nine years since I first pulled this project together, not halfway through my years of deep travels in east-central Europe that began in 2010. This collection numbers more than 800 photographs, already too many and too much to see, no matter how well seen and well earned each photograph may be. The number is part of the concept here, a testament of its own to the massive scope of the nothing that the genocide left. It is not clear to me that there are next steps to take in this journey from Bełżec, but perhaps in time I will draw into it my archives after 2015.