“There is no dialectical overcoming in the image.”

—Carlo Ginzburg

—Carlo Ginzburg

Bełżec, Poland, remnant of the unloading platform

1.

On the square of the small town of Izbica, Poland, forty miles southeast of Lublin on the Zamość road, stands a formidable monument to Jan Karski (1914-2000), the Polish resistance fighter whose heroic journeys between 1940-1943 brought crucial information from German-occupied Poland to the West, including eyewitness reports of the Holocaust as it was unfolding. In Polish and an (imperfect) English translation, the Izbica monument reads:

IN MEMORY OF

JAN KARKSI

(JAN KOZIELEWSKI)

JAN KARKSI

(JAN KOZIELEWSKI)

WHO AS AN EMISSARY OF THE POLISH UNDERGROUND STATE

IN OCTOBER 1942

MANAGED TO ENTER THE GHETTO * TRASNSITION CAMP

IN IZBICA

FROM WHERE JEWS WERE DEPORTED

TO THE GERMAN EXTERMINATION CAMPS

IN BEŁŻEC AND IN SOBIBÓR

IN OCTOBER 1942

MANAGED TO ENTER THE GHETTO * TRASNSITION CAMP

IN IZBICA

FROM WHERE JEWS WERE DEPORTED

TO THE GERMAN EXTERMINATION CAMPS

IN BEŁŻEC AND IN SOBIBÓR

HIS REPORT AS THAT OF AN EYE WITNESS TO THE GENOCIDE OF JEWS

WAS NEXT SUBMITTED TO THE LEADERS

OF GREAT BRITAIN AND OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

WAS NEXT SUBMITTED TO THE LEADERS

OF GREAT BRITAIN AND OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

HIS MISSION BECAME A PART OF HISTORY.

IN RECOGNITION OF THIS MISSION

HE WAS NOMINATED TO THE NOBEL PEACE PRIZE.

IN RECOGNITION OF THIS MISSION

HE WAS NOMINATED TO THE NOBEL PEACE PRIZE.

On the 75th anniversary of Polish Hero’s action

The Community of Izbica

Jan Karski’s Family

Jan Karski Society

The Community of Izbica

Jan Karski’s Family

Jan Karski Society

The simple purpose of a monument, to say the obvious, is to valorize: monuments are objects of memory first and history second, if at all, and valorization is why monuments to Karski stand in prominent Jewish spaces in Poland. One is next to the Rema synagogue in Kraków, and another is beside Warsaw’s POLIN museum, one of the largest Jewish museums in the world. The design of the Kraków and Warsaw monuments resembles others in New York, Washington and Tel Aviv: Karski is not on a pedestal, raised above the life of the world, rather very much in it, lost in thought on one side of a bench with a place for you and me next to him. And by the bronzing of the ones I have seen, people actually do sit with Karski. Perhaps the iconographic strategy even works: what we touch physically we touch psychically, and in this way Karski’s heroism remains close, relatable.

The shadow of the venerable Karski is the historical Karski, and as photographers know, shadows are unstable things by definition, changing shape and depth and contour according to the light, sometimes disappearing altogether. In some sense, the difference between the two Karskis is simply the difference between memory and history: the core task of memory culture is not primarily to transmit information, not to report, and not to engage in critical inquiry. Rather it is to sacralize, to create durable moral narrative, to lend poetic substance to fact. Collective memory is conservative by nature—once set, it is slow to change, lest the moral stability it provides falter. History, by comparison, is constantly subject to discovery. By definition it is subject to revelation, contestation, alteration. Karski is a man of our times in the process of being launched into a man for the future, and the resulting play of memory and history, substance and shadow is, from our vantage, alive as it will not be for coming generations. Or so I imagine.

Bełżce, Poland, the former prison-ghetto for Jews

In Karski’s book Story of a Secret State: My Report to the World, he describes a scheme by which he is able to enter a camp in the fall of 1942 that he believed was Bełżec (pronounced in Polish "Behw-zhets"). Bełżec was one of the three death camps—along with Sobibór and Treblinka—at the center of Operation Reinhard, the German plan to murder the Jews of the General Government in occupied Poland. Karski’s testimony includes this description of the camp:

It was on a large, flat plain and occupied about a square mile, surrounded on all sides by a formidable barbed wire fence. Inside the fence, at intervals of about fifteen yards, guards stood holding rifles with fixed bayonets, ready for use. Around the outside of the fence, militia men circulated on constant patrol. The camp itself contained a few small sheds or barracks. The rest of the area was completely covered by a dense, pulsating, throbbing, noisy human mass: Starved, stinking, gesticulating, insane human beings in constant, agitated motion. Through them, forcing paths if necessary with their rifle butts, walked the German police and the militia men. They walked in silence, their faces bored and indifferent. They had the tired, vaguely disgusted appearance of men doing a routine, tedious job…

We passed an old Jew, a man of about sixty, sitting on the ground without a stitch of clothing on him. I was not sure whether his clothes had been torn off or whether he, himself, had thrown them away in a fit of madness. Silent, motionless, he sat on the ground, no one paying him the slightest attention. Not a muscle or fiber in his whole body moved. He might have been dead except for his preternaturally animated eyes, which blinked rapidly and incessantly. Not far from him a small child, clad in a few rags, was lying on the ground. He was all alone and crouched quivering on the ground, staring up with the large, frightened eyes of a rabbit. No one paid any attention to him, either.

There was no organization or order of any kind. None of them could possibly help or share with each other and they soon lost any self-control or any sense whatsoever except the barest instinct of self-preservation. They had become, at this stage, completely dehumanized. It was, moreover, typical autumn weather, cold, raw, and rainy. The sheds could not accommodate more than two to three thousand people and every “batch” included more than five thousand. This meant that there were always two to three thousand men, women, and children scattered about in the open, suffering from exposure as well as everything else.

The chaos, the squalor, thee hideousness of it all was simply indescribable. There was a suffocating stench of sweat, filth, decay, damp straw, and excrement. To get to my post we had to squeeze our way through this mob. It was a ghastly ordeal. I had to push foot by foot through the crowd and step over the limbs of those who were lying prone. It was like forcing my way through a mass of sheer death and decomposition made more horrible by its agonized pulsations. My companion had the skill of long practice, evading the bodies on the ground and winding his way through the mass with the ease of a contortionist. Distracted and clumsy, I would brush against people or step on a figure that reacted like an animal, quickly, often with a moan or a yelp. Each time this occurred I would be seized by a fit of nausea and come to a stop. But my guide kept urging and hustling me along. In this way we crossed the entire camp…

And Karski’s testimony goes on to describe the loading of captives onto train cars:

The military stipulates that a freight car may carry eight horses or forty soldiers. Without any baggage at all, a maximum of a hundred passengers standing close together and pressing against each other could be crowded into a car. The Germans had simply issued orders to the effect that 120 to 130 Jews had to enter each car. These orders were now being carried out. Alternately swinging and firing with their rifles, the policemen were forcing still more people into the two cars that were already overfull. The shots continued to ring out in the rear and the driven mob surged forward, exerting an irresistible pressure against those nearest the train. These unfortunates, crazed by what they had been through, scourged by the policemen, and shoved forward by the milling mob, then began to climb on the heads and shoulders of those in the trains.

These were helpless since they had the weight of the entire advancing throng against them and responded only with howls of anguish to those who, clutching at their hair and clothes for support, trampling on necks, faces, and shoulders, breaking bones and shouting with insensate fury, attempted to clamber over them. After the cars had already been filled beyond normal capacity, more than another score of men, women, and children gained admittance in this fashion. Then the policemen slammed the doors across the hastily withdrawn limbs that still protruded and pushed the iron bars in place.

The two cars were now crammed to bursting with tightly packed human flesh, completely, hermetically filled. All this while the entire camp had reverberated with a tremendous volume of sound in which the hideous groans and screams mingled weirdly with shots, curses, and bellowed commands.

Bełżec operated from mid-March 1942 to the end of June 1943, and was built exclusively for the purpose of industrial mass murder. Its diesel exhaust gas chambers asphyxiated between 434,000-600,000 people, mostly Jews, as well as some Gypsies and non-Jewish prisoners, functioning with such lethal efficiency that only a single survivor provided postwar testimony.

Karski’s book was published in English in 1944, and did not appear in Polish until 1999, at which time Karski revised the text extensively, working with the Polish historian Waldemar Piasecki. The Polish version led, in turn, to revised editions in English and other languages; the text above is drawn from the 2014 edition. By the 1990s, it had evidently become apparent to Karski that he was mistaken in his belief that he visited Bełżec, which was, after all, the point of arrival for captives, not the point of departure. The notes to the revised edition name the site instead as Izbica Lubelska.

Izbica’s own history is highly unusual. It was a village without official town status until the middle of the 18th century, when it was given town status following the expulsion of Jews from nearby Tarnogóra. Virtually unique in Polish history, Izbica was monoethnically Jewish. Almost all other places in Poland where Jews historically lived were a quarter to a third or at most two-thirds Jewish, but Izbica was inhabited almost exclusively by Jews, lacking even a parish church. On the eve of the Polish partitions (1772-1795), Izbica’s population was 150 people. By the middle of the 19th century, it had gained repute as the base of the Chassidic master Mordechai Joseph Leiner—whose ohel was rebuilt in 1995—and by 1939, Izbica was home to 4500 people, 92% of them Jews.

To the Germans, Izbica must have looked like a ready-made ghetto. Immediately after occupying Poland in September 1939, they began deporting Jews in large numbers to Izbica, at first from western and central parts of occupied Poland. From the spring of 1942, Izbica became the largest transit ghetto in the Lublin District, from which Jews were subsequently deported primarily to the death camps at Bełżec and Sobibór. More than 10,000 Jews from Czechoslovakia, Austria and Germany were deported to Izbica, along with thousands of Jews from locals towns, with as many as 24,000 Jews passing through Izbica by November 1942, when the transit ghetto was liquidated.

Were it up to me to append basic historical commentary to the Izbica monument—a QR code or, in my style, chair and table with a weatherproof book—this is essentially what I would say, or in short: the current scholarly consensus holds that the horrors Karski describes took place not at Bełżec, but in Izbica, the antechamber to Bełżec.

Krasnystaw, Poland, the town center

From the first time I visited Izbica to photograph in 2010—I subsequently returned in 2010, 2014, 2018, 2023, and this year, 2025—I wanted to see for myself where things were, where the camp Karski described was. It seemed not that hard to find. The railroad enters the town from the northeast, turns just to the south of the town square and proceeds in a straight line southeast for a half-mile. The new and old Izbica stations are on that long straight stretch, and to the west of them, even today, is a large open field. In 1995, Karski went to Izbica with a television crew, who filmed him exactly on that stretch of track, as he points toward the field and says (in Polish), “...When I entered this camp, there were a couple of gates, not through the main gate, where they expelled Jews, but from a side gate, which was a little further.”

This year, I read for the first time—perhaps I should be embarrassed to admit this—the whole of Tomasz “Toivi’ Blatt’s 1997 memoir From the Ashes of Sobibór, beyond the sections on Sobibór itself, where Blatt was imprisoned and from which he escaped in a revolt staged by the camp Underground in 1943. Blatt’s hometown was Izbica. He was in Izbica until October 1942, and again from January 1943 until his deportation to Sobibór in April of that year, and his book provides an extraordinarily detailed account of the Holocaust as it unfolded in Izbica, including roundups and deportations. Blatt’s text does not square with Karski’s in one crucial detail: Blatt’s account contains no mention at all of a fenced camp in the town.

Other sources confirm this. Contemporary Bełżec contains an excellent small museum, a branch of the Majdanek State Museum. It was there in 2014 that I saw for the first time an extensive excerpt of Claude Lanzmann’s devastating 1978 interview with Karski, part of which Lanzmann included in his epic film Shoah. Addressing locations important to the history of Bełżec, the museum informs visitors:

The location of the ghetto in Izbica was determined by its location towns near the railway line leading to the death camps in Bełżec and Sobibor. [The] geographical location of the town, which is surrounded on three sides [by] hills, and the fourth fenced off by the river, meant that the ghetto did not have to be in any way way fenced.

Likewise, historians Robert Kuwałek and Martin Dean, writing for the United States Memorial Holocaust Museum’s (USHMM) Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1939-1945 state positively:

A closed ghetto did not exist in Izbica at the time. However, Jews were not allowed to leave the designated borders of the town, and this regulation has led some observers to conclude that the entire town resembled a large “open ghetto.” It was bordered on three sides by hills and, on the fourth (Tarnogór) side, by the Wieprz River. Jews could not even move freely within the town.

I am an artist and not a historian, and so I wrote to several historians asking about the discrepancy—Jakub Chmielewski of the Majdanek State Museum, the Karski historian Adam Puławski, the eminent Holocaust historian Christopher Browning, and Peter Gengler of USHMM. All of them said that they had not looked into it, but yes, there are reasons to doubt. I decided to see what I could not figure out for myself.

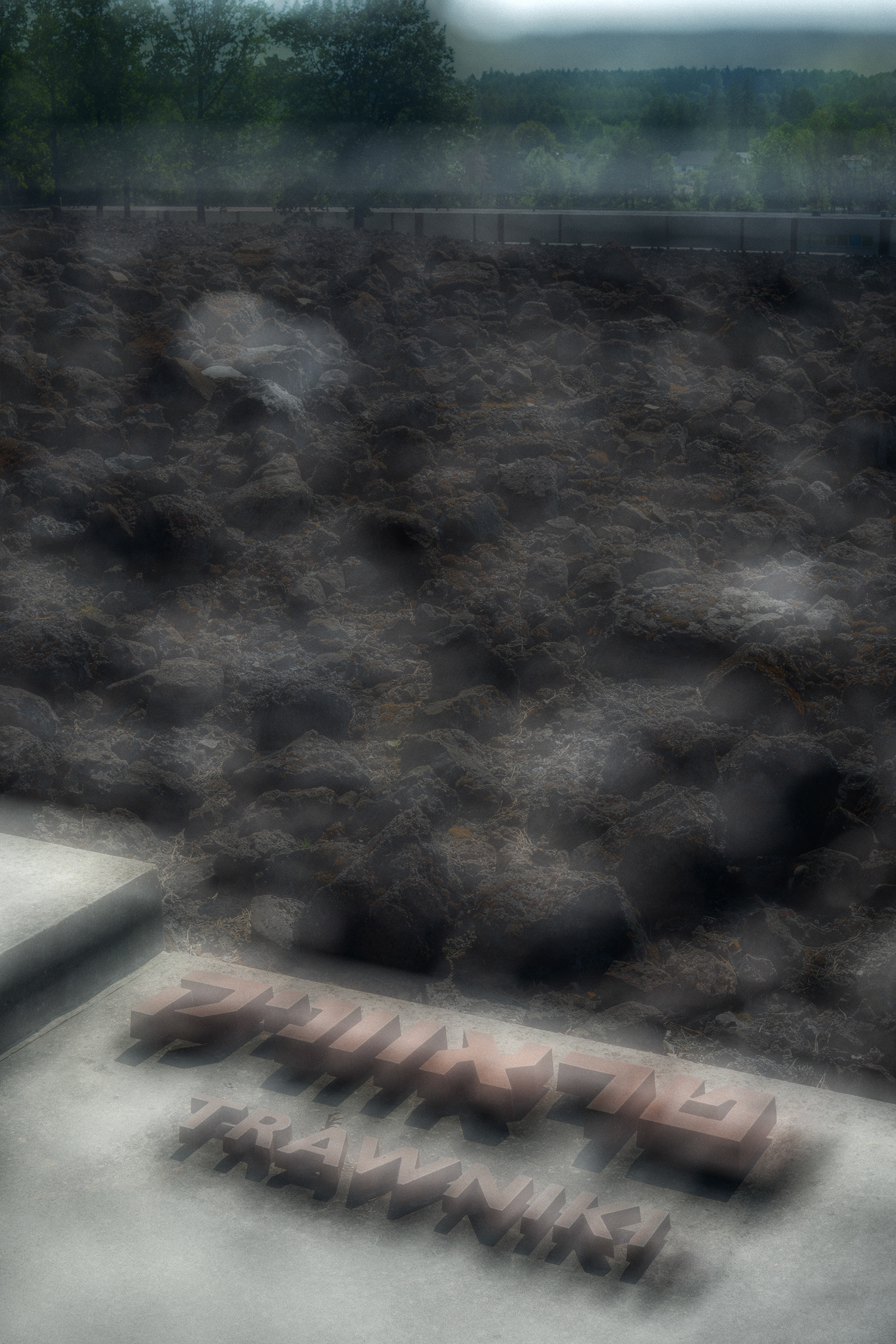

Trawniki, Poland, the site of the former transit camp

Besides Izbica, five other towns in the Lublin District roughly in the vicinity of Izbica had transit ghettos functioning in 1942: Piaski, Rejowiec, Krasnystaw, Bełżyce, and Trawniki. These, it would seem, would be the reasonable next places to look, but to think so is already to accept certain premises. Most importantly, it is to accept that the problem with the Izbica attribution does not generally disqualify the text’s status as report. It is common, in other words, for historical testimonies to have errors of fact, especially concerning traumatic material. (How Karski’s seeing is touched by an inability to see is something I take up below.) Lacking an independent account of Karski’s activities, determining where Karski was has to proceed using his testimony alone.

Parsing the text carefully for key geolocational details that I could directly study in visits to the six candidate sites, I found four:

1. The distance of the site from Lublin. Karski writes:

Early in the morning of the day we had selected, I left Warsaw in the company of a Jew who worked outside the ghetto in the Jewish Underground movement. We took the train to Lublin. A hay cart was waiting for us there. We took the dirt tracks because the farmer who was transporting us wanted to avoid the busy Zamosc road. We arrived in Bełżec shortly after midday…

By hay cart Karski means a horse-drawn cart. The site Karski describes, in other words, is located between Lublin and Zamość, close enough to Lublin to travel there by horse cart in a few hours.

2. The site’s distance from the town of arrival. Karski writes:

The camp was about a mile and a half from the store. We started walking rapidly, taking a side lane to avoid meeting people and possibly having to endure an inspection. It took about twenty minutes to get to the camp but we became aware of its presence in less than half that time. About a mile away from the camp we began to hear shouts, shots, and screams. The noise increased steadily as we approached.

3. As quoted already, the camp sat a large open field. Of course an open field 80+ years ago may well not be an open field today, but it is often possible to study the age of buildings and the stages of a town’s development.

4. The camp’s proximity to a rail line. Much of Karski’s description is of prisoners being loaded onto rail cars, which is to say the site should be located near a railroad.

I added to these four items two more non-geographical factors, to round out my criteria:

5. Documentary evidence of a fenced camp.

6. Evidence of deportations in the fall of 1942.

With some ideas about how to photograph, I got on the road.

Niedrzwica Duża, Poland, site of the holding place of captive Jews beside the railroad tracks

Concerning the first criterion, here are the distances between Lublin and the transit ghettos in the direction of Zamość:

Lublin - Izbica, 40 miles

Lublin - Piaski, 15 miles

Lublin - Rejowiec, 38 miles

Lublin - Krasnystaw, 33 miles

Lublin - Bełżyce, 14 miles

Lublin - Trawniki, 22 miles

Lublin - Piaski, 15 miles

Lublin - Rejowiec, 38 miles

Lublin - Krasnystaw, 33 miles

Lublin - Bełżyce, 14 miles

Lublin - Trawniki, 22 miles

If a horse cart on backroads travels at a speed of, say four miles per hour—which would seem relatively fast—this presents a different problem for Izbica, namely it would be a day’s journey to get there there from Lublin, not a few hours. The same would be true for Piaski, Rejowiec, and Krasnystaw.

Concerning the last two criteria, evidence of fences and deportation records for 1942, I sourced information from USHMM’s Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, Volume II, Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe: Lublin Region, published in 2025. These are the numbers for those deported, a portion of the total killed in the roundup and deportation actions. I note that USHMM encyclopedia entries are compiled by different researchers from a variety of sources, and precision varies, both concerning exact dates and exact numbers.

Izbica: March 24 (2200 to Bełżec), May 12-15 (hundreds to Majdanek and Sobibór), June 8 (2000 probablay to Bełżec), July 6-7 (unknown number to Sobibór), October 19 (5000 to various places), November 2 (5000 to Bełżec and Sobibór)

Piaski: March 16 (2500 marched to Trawniki), April 6 (~3500 likely to Bełżec and/or Sobibór, October 22 (~5000 to Trawniki)

Rejowiec: April 7 (~1900 to Bełżec), August 9 (~1300 to Sobibór)

Krasnystaw: May 14 (700 to Majdanek), May 14-15 (5200 to Sobibór), August (small group to Sobibór), October (liquidation to Izbica and hence to Bełżec)

Bełżyce: May 11 or 23 (~500 to Majdanek), October 2 (hundreds to Majdanek), October 13 (hundreds to Treblinka, thousands to Sobibór)

Trawniki: March 17 (2500 to Bełżec), April (~5000 to Bełżec), ~October 23 (thousands to Sobibór)

Here, cogently, are my findings in light of all the criteria, after having visited each potential site:

Izbica / At 40 miles from Lublin, it is implausible that it could have been reached by horse cart in a few hours. The site of the camp is indeed about a brisk twenty minute walk from the center of the town, and a large field still exists there, just beside the railroad line. There is no evidence for a fenced camp, but there were deportations in October 1942. Of the six criteria, Izbica satisfies four.

Piaski / Located 15 miles from Lublin, the town could be plausibly be reached by horse cart in a few hours. Records indicate that two ghettos existed, one of them fenced, but both were in the center of the town, not in a large field. (The Jewish cemetery, where hundreds were massacred, is still at the very outskirts of the town, next to agricultural fields, but there is no evidence of a camp existing near it.) There is no direct rail access in Piaski; the closest access point to the railroad is Biskupice, five miles away, but this town is not mentioned in any documents. USHMM specifies at least one large deportation occurring by marching prisoners to Trawniki, seven miles away. Deportations from Piaski did occur in October 1942. Of the six criteria, Piaski satisfies three.

Rejowiec / At 38 miles from Lublin, it is unlikely to be reached in a few hours by horse-drawn cart. The center of the town is located a little more than a mile south of the railroad, plausible to reach in a brisk 20 minute walk. Open fields even today surround the tracks on a wide plain extending to either side. There is no evidence for a fenced ghetto, and the evidence for deportations in the fall of 1942 is mixed. The UK-based Holocaust Historical Society’s article on Rejowiec reports a deportation of 2400 from Rejowiec to Sobibór on October 10, and USHMM’s encyclopedia entry reproduces most of this text, omitting mention of this deportation specifically. Without verification of October deportations from Rejowiec, of the six criteria, Rejowiec satisfies three.

Krasnystaw / Located 33 miles from Lublin, it is not reasonable to reach the town in a few hours by horse cart. A ghetto was located in the Grobla district of the town, across the Wieprz river from the center, certainly walkable from the main square in a brisk 20 minutes. That Karski does not mention crossing a river seems notable—one might suspect this was a detail that would have fixed in his mind. This ghetto was close to the rail line, but not on a wide field because there were no wide fields: the ghetto existed in a compressed area between the river and the hills that rise just to the east of the tracks. There is no evidence that the ghetto was fenced, but deportations did occur in October 1942. Of the six criteria, Krasnystaw satisfies three.

Bełżyce / A substantial ghetto existed in the town, whose name resembles Bełżec. Jews in Bełżyce were forced onto rail cars in the town of Niedrzwice Duża, some six miles away. This is an unusual name, literally meaning “Big Place of No Trees,” but inasmuch as the Polish words for tree and door are very close (drzwi/drzewo), more poetically it could be rendered “Big Non-Door,” perhaps a general name for every one of these locations in my admittedly quixotic pursuit. The town of Niedrzwica Duża is located a brisk 20 minute walk northeast of the railway station. Open land extends on both sides of the track, on which new structures are intermittently built. From Lublin directly to Niedrzwica Duża is approximately 13 miles, the shortest distance of any of the candidate towns, and plausibly reached in a few hours by horse-drawn cart. There is no evidence that a fenced camp existed at the site, and deportations did occur in October 1942. Of the six criteria, Bełżyce (Niedrzwica Duża) satisfies five.

Trawniki / Located 22 miles from Lublin, the town could arguably have been reached in a few hours by horse-drawn cart. Most of the town was occupied by the infamous SS training center for Ukrainians and other German collaborators, where they learned the logistics and techniques of genocide. The nature of the camp changed over time, and it also functioned variously as a forced labor camp, a prisoner of war camp, and an annex of Majdanek. It was fenced and heavily fortified, and located on the railroad line. The large number of auxiliary police, identified as “Estonians” in Karski’s narrative, subsequently corrected to be Ukrainians, might explain the ease with which Karski obtains a uniform, another of the text’s important episodes.

Wartime maps of Trawniki divide the camp roughly into four sections: the SS and Ukrainian barracks, a section of workshops, an old area for prisoners, and a newer and larger labor camp for forced laborers. USHMM scholarship dates the construction of this camp to the summer of 1942, when forced labor was dramatically increased at Trawniki. The new prisoner camp was expanded in the spring of 1943 to hold the approximately 6000 prisoners, who were imprisoned there until the camp’s liquidation in November 1943. Open fields sat between the new camp and the tracks, which the maps label “for future expansion,” and this area appears to have been inside the fence. It could have been that the site Karski saw was this space “for future expansion” located between the new prisoner camp and the tracks—that this was the location of Jews passing through Trawniki, who were not integrated into the camp prisoner system. Alternately it could be that Jews-in-transport were kept in the far end of the new prisoner camp, before the construction of new barracks in 1943, and it was here that Karski walked among them. Perhaps it was both locations.

It is plausible that the space “for future expansion” and/or the far end of the new prisoner camp was a 20 minute walk from the shop where Karski begins his journey, but it is not easy to say where such a shop would have been. Unusually for Polish towns, Trawniki did not have a central square, especially perplexing given that Trawniki is one of the oldest towns on the central Wieprz river, dating to the early Middle Ages. Town histories describe the change in its ownership over the centuries and its parish history, without mentioning it as a commercial center. The first significant industry appeared in the town with the construction of a sugar factory in 1889, which became a textile factory in 1932, which in turn became the center of the German training center. The closest thing to a town center today is a collection of shops near the railway station, which is roughly confirmed in a 1944 aerial photograph. Reasoned speculation would put the shop somewhere there.

Exactly how deportations happened from Trawniki in October 1942 is not altogether certain. USHMM’s essay on Trawniki does not specify October deportations; however, the essay on Piaski states that on or around October 22, several thousand Jews were rounded up and taken to Trawniki by Gestapo, Gendarmerie, SS Ukrainian auxiliaries, and Polish (Blue) Police, to be sent later to their deaths at Sobibór. Around the same time, some 3000 Jews from Łęczna were marched to Piaski and then to Trawniki, also destined for Sobibór. If Karski went to Trawniki in the last week of October 1942, it seems altogether possible that these are the Jews he encountered. How he came to believe their destination was Bełżec and not Sobibór is impossible to say.

Of the six criteria, Trawniki seems closest to satisfying them all. To confirm that Trawniki was Karski’s Bełżec requires a level of informational granularity not quite available, like a lens whose circle of least confusion is still too indistinct. But on the whole, Trawniki seems to me a much better guess than Izbica, and Bełżyce/Niedrzwica Duża at least as good as Izbica, or even a little better.

Piaski, Poland, the Jewish cemetery

2.

There is no reason to doubt that Karski was speaking truthfully when he walked the tracks of Izbica 57 years after his experience and pointed to the site of the camp he entered. But truthfulness is not truth: people are wrong every day about the facts undergirding what they truly believe, and concerning the past, truthful accounts are not sufficient to establish what was actually true. Exactly how Karski came to believe Izbica was his Bełżec would seem to require the input of those who knew him. Perhaps he came to this opinion himself, perhaps with Piasecki, or others. The revised edition of Story of a Secret State treats the revisions as if they were minor corrections of fact. The notes to the chapter on “Bełżec” state curtly:

The historic veracity of these facts has been reaffirmed by scholars and by Jan Karski himself in 1999, with the publication of the Polish edition of Story of a Secret State. It was in fact a Ukrainian (and not an Estonian) guard, as all the guards in Bełżec and the neighboring camps were Ukrainian [Chapter 30, note 3].

The camp to which Karski was taken was Izbica Lubelska and not Bełżec. Lesser known of the two, as an annex of Bełżec, Izbica Lubelska nevertheless held an important place in the extermination program of the thousands of Jews in “Operation Reinhard.” After a de-lousing operation in Izbica Lubelska, the Jews were either executed in the camp or (the majority) transported to Bełżec, amidst the violence and horrors described by Karski [Chapter 30, note 4].

We can ask: what kind of error imperils testimony, and what kind is incidental? If Karski’s claim to having seen Bełżec can be amended once without damaging the veracity of its substance, why not twice? Is my argument that he saw Trawniki and not Izbica a negligible re-correction in this sense? It could be, but if so, it is the kind of trifling improvement that sits at the edge of a precipice of difficulty. It already requires, as I have said, a certain suspension of doubt to accept that Karski was in Trawniki. For the reasons above, I think that such a suspension of doubt is warranted, but for those more doubtful than me, Karski’s text begins to look considerably shakier.

The emblematic skeptic on this point is, for me, Adam Puławski, part of whose career has been devoted to exploding historical myths about Karski, and to drawing attention to ways that Karski’s work was not principally driven by a desire to alert the Allies to the genocide of the Jews of Poland. The latter is not a revelation. Karski openly admits in his book and later reiterates to Lanzmann that his primary purpose was to work for the future of the Polish state, to carry messages between the Polish Underground and the Polish Government-in-Exile, and that his information on the Jews was brief and not the center of his conversation with Roosevelt. Puławski’s 2018 book Wobec „niespotykanego w dziejach mordu” [In the presence of “a murder unheard of in history”] exhaustively traces Karski’s role and contributions to his main tasks, in a meticulous study of the flow of information on the Holocaust from the local levels through the Polish Underground and to the Government-in-Exile. Writing to me by email, Puławski says cogently:

We know he was not the most important witness [of the Holocaust as it was unfolding], certainly not the first, even when it comes to reporting on the Warsaw Ghetto. The Holocaust was not an important issue for him… We know that, like other witnesses many years after the events, he claimed authorship of other witnesses’ actions and added secondary knowledge to primary knowledge. [For these reasons] we don't treat Story of a Secret State as a source. So no, in my opinion Karski was not in Bełżec, [rather] he used this name to give the impression that he was a very important eyewitness. If you ask me where was Karski, my answer is: I do not know. But for me it is not a crucial question concerning Karski's mission… I think that no one knows where Karski was.

True to its non-centrality, Puławski’s 871-page book gives a single paragraph to the topic of Karski in Bełżec, in which Puławski presents evidence that Karski’s story varied in its early versions. According to Puławski, for example, in December 1942, Ignzcy Schwartzbart (one of the Jewish representatives on the Polish National Council to the Government-in-Exile) reports that he spoke with Karski, who “witnessed the mass murder of a transport of six thousand Jews in Bełżec.” However, in a March 1, 1943 report, Karski claims to have been “on the outskirts of Bełżec,” and then at “the sorting point located about fifty kilometers from the town of Bełżec.” In a July 1943 radio broadcast, Karski speaks of having been in a “sorting camp near Bełżec,” but later in 1943 descrbes being in the Bełżec camp itself. This is essentially the same version of the story that appears in Story of a Secret State, which is likewise what he tells Lanzmann in 1978. Puławski’s case seems plausible: Karski’s vaunted photographic memory aside, it is likely he knew the difference between a transit camp to Bełżec and Bełżec itself, and was not scrupulous about it, perhaps because he figured out that he could augment the impact of his testimony by calling it “Bełżec.” For Puławski, in general, the force of the mistake is weak, but not because of its marginal importance to the integrity of Karski’s testimony. On the contrary, for Puławski, Karski is an unreliable narrator who had no serious historical task concerning the fate of Jews in occupied Poland in the first place. For Puławski, Karski’s historical status is vastly overstated, and Puławski appears indifferent to Karski’s memorial status, or perhaps sufficiently pitched toward anti-hagiography that he views Karski’s overall diminishment positively.

Or to say the point differently, Puławski’s attitude to Karski echoes Karski’s own account of his 1943 meeting with U.S. Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, in which he describes the destruction of the Jews of Poland as it is happening. In Lanzmann’s film, Karski remembers Frankfurter saying:

I was told that you came out of hell. And I was told that you are going back to hell… Young man, I am no longer young. I am a judge of men. Men like me with men like you must be totally honest. And I am telling you: I do not believe you! Ciechanowski [Jan Ciechanowski, ambassador of the Polish Government-in-Exile to the U.S. between 1941-1945] breaks in. Felix, what are you talking really about?… He comes with the president, he was checked, rechecked 10 times, in England, here! Felix, he's not lying! Frankfurter, still walking: Mr. Ambassador, I did not say that he is lying. I said that I don't believe him. These are different things.

I should note parenthetically, vis à vis Karski’s comment about the site being some fifty kilometers from Bełżec: Bełżec is 130 km south of Lublin and 65 km south of Izbica, in other words from Lublin it is necessary to go far past all the Lublin District transit ghettos to get to Bełżec. To measure distance in relation to Bełżec appears to be a post-facto way of speaking, or could suggest a separate encounter with Bełżec. The latter is not impossible given that the town lies between Warsaw and Lviv, where Karski studied law before the war and where he carried messages to the Lwów Underground at the end of 1939 and the beginning of 1940, though it would have been two years before the death camp began to function.

Rejowiec, Poland, in the former prison-ghetto for Jews

Without imputing anything to Puławski, it is a certain kind of hard skeptic that I set out to convince—someone for whom credibility depends on verifiability, full stop. For this person, Karski’s witness lacks credibility until we can finally pin down where he was with reasonable certainty. Until then, Karski’s text is either of little or no historical value—the skeptic asserts once again that truth is not truthfulness—or its value derives from a change of genre, its transition from report to moral fable, in which truthfulness does not depend on truth. (And I should say that there is a certain kind of hard skeptic I do not care to convince, namely Holocaust deniers and revisionists. That critical inquiry undertaken in good faith may give courage to those who undertake it in bad faith is a miserable problem, but not a reason not to seek.)

To the responsible skeptic, I reply: even if the argument for Trawniki does not not once and for all establish the site of Karski’s Bełżec, it should be enough to amend the evaluative criteria from the simple category of true-because-verifiable to something more appropriately difficult: true-but-unverifiable. Karski’s account demands a non-reductionist form of historical inquiry, which understands acts of witness holistically as the sum of factual, affective, and moral truths that cannot necessarily be broken down into factual, affective, and moral claims to be evaluated separately. By holistically I do not mean that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts—though I understand that precisely such wholes are often what we mean by, say, culture, or civilization, or personal identity, or self. It is enough to say that a sum is a sum, an additivity that would not be what it is without its parts. Something becomes true-but-unverifiable when its co-incident or inter-arising claims have both objective and subjective purchase, in a space marked out negatively, according to what it is not. It is not, as I have indicated, in thrall to the idea that the gold standard of verifiability is a putative one-to-one correspondence between an account of the world and the world-in-itself. Likewise it is not derived from pre-formed outcomes, in this case doing history for the sake of memory, i.e. validating Karski’s established memorial status as hero. Also the space of true-but-unverifiable is not content to consign an account like Karski’s to the limbo of undecidability, to remain in the company of other marooned acts of witness we cannot call either true or false, with the consignment itself being neither obviously consequential nor inconsequential.

Izbica, Poland, the tracks on which deportations to the death camps ran

To the factual claims I have laid out that Karski was at Trawniki, it seems essential to me to factor in—it is impossible to factor out—the other dimensions of Karski’s testimony.

The literary structure of the text is immediately evident. Karski begins by setting the scene: it is a few days after his visit to the Warsaw ghetto, and the same Bund leader is to arrange a visit to “a Jewish death camp.” Next he informs us of the overall plan, his disguise and its trustworthiness, and his confidence that he would not be caught. The narrative proceeds by staging his travel to the camp, his arrival in “Bełżec,” his suiting up in a local store run by a clandestine member of the Polish Underground, his conversation with the “Estonian” collaborators and especially his alibi, that he is there to learn the black market in “saving” Jews. As he is passed from hand to hand, the reader is passed cross-sectionally through the lower levels of camp organization, and at the same time geospatially through the fence and into the camp itself. In this way the key contrast is established between the (corrupt) discipline of the military bureaucracy and the delirious chaos of the world of the victims, where there was “no order of any kind,” to return to the section of the text quoted above. The rhetorical effect is a kind of Dantean descent into the pit of hell. In the pit, Karski is shown the way to the railroad siding and witnesses the condemned being pushed onto trains, and ventures his understanding of the trains as the primary instruments of mass murder. Dazed and numbed, he is seized from behind by the guard who smuggled him in, and the whole process is reversed: he exits the camp and returns to the store. The account ends with a series of purgative acts: in the store he washes himself frantically, vomits violently for a day and a night until he is vomiting blood, falls into a long stuporous sleep with the aid of whiskey, finally returns to Warsaw and attends Mass, where the priest calls him to the altar and asks him to bare his chest, then hangs a scapular around his neck. Karski describes the deep spiritual safety he felt in wearing it going forward, and in this sense the chapter ends redemptively.

All of this is to be compared to the interviews Karski gives to Lanzmann in 1978, several hours of which are now available in their raw form through USHMM’s website. The sections concerning “Bełżec” appear in sections no. 4 and 5 of the 11 that USHMM has posted, reels 13-15 of Lanzmann’s own system, clapperboard nos. 286a-307. It is not a single interview. In fact Lanzmann begins the same conversation three times with Karski, going deeper each time. The first attempt is focused on the facts surrounding Bełżec, and the tone is sometimes contentious, Lanzmann repeatedly interrupting Karski for clarification. Lanzmann seems to have grasped that this approach was blocking what he intuited was inside Karski to say—intuited because these interviews are the first Karski gave in decades on the specifically Jewish aspects of his testimony. In the second and third attempts, Karski’s verbal account becomes completely riveting. Skipping the contextual information about the camp and also the framing stages of his narrative, Karski goes directly to his encounter with the camp itself. Here the non-verbal dimensions of his testimony rise to the surface: his large frame grows rigid and then trembles as he speaks; his eyes seem to lose focus on the immediate world surrounding him (his own home) and regain it in phases; his face winces and cringes, and his voice grows tense and forceful and alternates in pitch. He stutters and blenches, and sometimes his speech breaks off. At one point he breaks down altogether, weeping uncontrollably, and abruptly leaves his seat as we hear Lanzmann pleading, “Please, stay, stay. Stay, stay.” The camera goes off and sometime later, they begin again. Karski says:

At the time I was stronger. I understood my mission. I was not supposed to have any feelings. And I was… camera. And I didn't have any feelings… for some time.

The reference here to a camera is striking, inasmuch as the verbal—affectively impassioned—form of Karski’s witness is non-narrative, and photographs in themselves are non-narrative objects, which beckon narrative from us to make sense of them. In this moment we understand that Karski’s mission demanded that he find and sustain a state of controlled mind in which he could register and retain enormous amounts of information to transmit to others, mostly in the service of his main purposes (resisting the destruction of Poland and advocating for its interests among the Allies). The genocide of the Jews, in a sense auxiliary to his mission and which he makes clear he agreed to witness apart from the Polish Underground, pushed Karski past his limits. The oral account provides details that the written account omits:

This moving, moving—some organism with legs, with eyes, with noses, whatsoever. I controlled myself. I realized again—no feelings—stay here, look, look, look, no feelings.

And then after a certain time, yes, apparently, it came too deeply into me—humans. They are individuals here. And then I lost control. I realized, I don't know what I would do. I might jump at some Gestapo and start fighting him. I might go with the Jews to the train. I realized—things got out of control with me.

I go back in the direction of that gate. I entered. Now, the Estonian—

The effect is to watch a man standing before an assault of images held within himself, themselves standing in for a confrontation with evil and inhumanity powerful enough to drive him spontaneously to suicide. And we realize: at some fundamental level, Karski could not experience what he was experiencing, could not look at what he was looking at. The very thing Karski saw wrote itself as a kind of spectral signature on his mind, and the act of recalling precisely meant finding the kind of memorial “light” by which such an inscription would appear. Lanzmann grasped that such recollection often does not appear by the light of chronicle, and is subsumed by the ordering habits of ordinary perception.

Or to say it differently, Karski’s Bełżec did to him what Shoshana Fellman and Dori Laub report as common in certain kinds of traumatic events: it induced “unwitnessability,” overwhelming him psychically and disabling the ability to coherently account for what he saw as it was happening. This truth of experiential rupture is much more evident in the oral testimony than the published account, but in either case lives between the words of what Karski says, and likewise between the lines of whatever the historian can reconstruct. Its presence is not a reason to doubt the credibility of Karski’s witness, but the contrary—it is the affective seal of his credibility, apart from questions surrounding verifiable facts.

Bełżec, Poland

There is a certain poetic convergence in the all-but-unwitnessable camp being very hard to find in the world today, as there is between the camp’s mercurial presence in memory and the ways that representational acts change the thing represented. If the ghost of things-in-themselves haunts what we say about them, in Karski’s case this haunting seems to me at the center of the extraordinary moral courage that stanchions Karski’s testimony.

What Karski agreed to see in the Warsaw Ghetto and in his Bełżec was—we should remind ourselves—unprecedented in human history at that time, a crime without a name when it occurred. Presenting himself before the annihilative whorl of the genocide, he allowed it to enter him, to act on him, and to act through him. The elements of what has come to be called the “Karski Report” arrived in London in November 1942, and led to the December 17, 1942 joint declaration by the Allies titled “The Mass Extermination of Jews in German Occupied Poland,” the first official information to the Western public detailing the Holocaust, including the procedures of industrial mass murder at the extermination camps of Treblinka, Sobibór, and Bełżec. I note that Puławski’s research has opened questions about whether the Karski report was entirely written by Karski, or whether parts were misattributed to him; at this point his sole authorship is unconfirmed. But in some sense this question is not critical. It seems to me that Karski’s courage was to allow the things he did control—information and analysis that he dictated into hundreds of pages of reports, mostly concerning the political problems of Poland under occupation—to act as a moral accelerant concerning the things he did not control as well, specifically concerning the fate of the Jews. Karski knew intuitively how to direct the force of the extirpation as he received it away from the silence and silencing central to it.

If, as Carlo Ginzburg notes, Tolstoy’s philosophy of history correctly asks that we open ourselves to the forces greater than individual actors, and attend to the gaps between real events and “the fragmentary and distorted recollections” that become historical accounts, and if the best answer to this predicament is more information rather than less, Karski’s example points to the gyroscopic balance of the truths of what Ginzburg calls “just one witness.” Certainly Karski’s example mitigates Benedetto Croce’s critique of Tolstoy, essentially that at any given point in time we have all the history we need.

In this sense, if blessing is the metier of memory, it is a blessing that the camp Karski saw abides now—for the future, for us—in semi-dislocation, a state of drift that is paradoxically not diminished by the discovery of where Karski was. Karski’s Bełżec is not Bełżec as it was then, or Bełżec as it is now in its aftermath. Rather Karski’s Bełżec is a pendulum swinging between the places it could well have been—Trawniki, Izbica, Krasnystaw, Piaski, Rejowiec, Bełżyce/Niedrzwica Duża—a camp still at large, as it were. Karski's Bełżec exists, now, as a perpetual coming-to-be according to our own feeling for it and, like Karski, our capacities to stand before abomination as it unfolds before us, against what we are accustomed to thinking, what we prefer to think, what violates the existing coherence of our thinking. Karski’s Bełżec is constantly on the way to Bełżec, disobedient to the binary categories of completed and uncompleted atrocity. The Karski worthy of our memory culture is not the hero who looked once, but the figure of our own noble conscience, prompting us not to harden the Holocaust into an inert object of memory, demanding that we look clearly at our own evolving moment.

Trawniki, Poland, site of the loading of captive Jews onto railroad cars, in my view the probable location of Karski's Bełżec

Traveling east in the summer of 2025 to look for and into Karski’s Bełżec, with Karski's spirit sitting beside me on the long train journey, this poem pushed itself out of me:

Those we did not murder by warplane and sniper

we murdered by starvation, in the name of destroying future disasters.

No black sun, we pronounced, should rise over us again,

even as the taste of bomb salt on skin is spread

far across the rubble. The journalists intoned: “historians will judge.”

Their grave voices chorused our depravity.

far across the rubble. The journalists intoned: “historians will judge.”

Their grave voices chorused our depravity.

A few of us insisted: there are two genocides for us now,

two and not one, two that are one,

the one that made us and the one that we made.

two and not one, two that are one,

the one that made us and the one that we made.

The others, most of us, insisted that murders be ranked

in sacredness, and Gaza cannot be seen

from the towers of our Jerusalem.

in sacredness, and Gaza cannot be seen

from the towers of our Jerusalem.

They called down as their witnesses

the seraphs of our own millions, who glowered

with demonic eyes that yes and yes,

the seraphs of our own millions, who glowered

with demonic eyes that yes and yes,

there are many who hate us.

But me,

I know them differently, our millions.

I know them where they live:

in their ash-field addresses, the warehouses and barns

and synagogues where they were torched,

in their ash-field addresses, the warehouses and barns

and synagogues where they were torched,

the forest pits they were shot into. I still visit them.

At home they are not as their ventriloquists think.

In fact they are reticent, with little reason to speak.

At home they are not as their ventriloquists think.

In fact they are reticent, with little reason to speak.

They go on rotting, resiliently. Their rooms are wild

with goldenrod, small-flowered touch-me-nots,

all manner of alien plants. They are expert

with goldenrod, small-flowered touch-me-nots,

all manner of alien plants. They are expert

in the mineral cycle of the elements, given to ponder

bird migration and the ways the living quietly assume

the non-existing of other lives.

bird migration and the ways the living quietly assume

the non-existing of other lives.

At night they gaze at God’s great scythe

turning its silver blade from full to new,

and occasionally they burn the dross

turning its silver blade from full to new,

and occasionally they burn the dross

that collects on the slopes of the epoch,

in red reverse falls. From the millions I learned:

there is no time to wait for the historians.

in red reverse falls. From the millions I learned:

there is no time to wait for the historians.

Our mourning, they told me, measures our maturation.

That time fades memory is nothing to grieve,

but that it shatters honesty, yours, now, yes.

That time fades memory is nothing to grieve,

but that it shatters honesty, yours, now, yes.

Listen: from our own library

the lined-out hymnodies and the nigguns

climb the rungs of lament, generation by generation,

the lined-out hymnodies and the nigguns

climb the rungs of lament, generation by generation,

for every next day that carves a new facelessness

for a child. That child was possibly yours,

or even you, and now will not be.

for a child. That child was possibly yours,

or even you, and now will not be.

Izbica, Poland, the site that Karski (likely wrongly) identified in 1995 as the camp he visited

I am, as I have said, an artist and not a historian, albeit the kind of artist not satisfied that art should be a realm hallowed for subjectivity as against the profane world, rather compelled to return subjectivity to the world, in trust and in provocation equally. Perhaps this is a distinctly Jewish artistic way, one expression of the Jewish instinct to make solitary truths relational, a Jewish faith in the sensuousness of thought, a Jewish curiosity about crossings—cross-pollination, cross-contamination, cross-examination.

I have mentioned Karski’s self-likening to a camera in his interview with Lanzmann. In his written account, he anticipates the incredulity he expected to meet, conjuring camera-derived images as the gold standard of proof:

I know that many people will not believe me, will not be able to believe me, will think I exaggerate or invent. But I saw it and it is not exaggerated or invented. I have no other proofs, no photographs. All I can say is that I saw it and that it is the truth.

I ask: do we already understand what a photograph looks like, i.e. what it should look like for the sake of memory? For a long time, I have thought that memorial inquiry should draw freely on the (enormous) plastic range of photography as a medium. In the case of traumatic historical memory, inherently disrupted and rupturous, I see no reason why photography needs to be contained to that aspect of its nature capable of imparting a sense of control over the world beheld, as for example in conventional images that link qualities of presence with visual sharpness and stillness. The communicative capacity of photography is far broader.

Without dwelling too much on it—it is a topic, perhaps, for another essay—what appears in photographs might stand for itself, or might stand for what once existed and has now disappeared. The former I would call photography’s ontology of presence, and the latter its ontology of impresence (a neologistm I use to distinguish erstwhile presence from absence, i.e. that which never appeared). Photography’s appearances can conjure both presence and impresence, and can do so aesthetically using sharpness or unsharpness, the latter produced optically through the way a lens is unfocused, or temporally through differential long exposure with the world’s motion, or the camera’s or both. Crossing these continuums produces a conceptual map something like this:

Ontology of presence

1. | 2.

Visual idiom of sharpness Visual idiom of unsharpness

3. | 4.

Visual idiom of sharpness Visual idiom of unsharpness

3. | 4.

Ontology of impresence

1. Visual sharpness for the sake of an ontology of presence

2. Visual unsharpness for the sake of an ontology of presence

3. Visual sharpness for the sake of an ontology of impresence

4. Visual unsharpness for the sake of an ontology of impresence

2. Visual unsharpness for the sake of an ontology of presence

3. Visual sharpness for the sake of an ontology of impresence

4. Visual unsharpness for the sake of an ontology of impresence

As a visual way of handling the complications of the search for Karski’s Bełżec, I developed a compound descriptive method. With the camera on the tripod, I made four exposures—one for universal sharpness and color, one for universal sharpness and monochrome, one for unsharpness and color, and one for unsharpness and monochrome. In Photoshop I layered them to make a single photograph which combines aspects of each contributing image. These are, in other words, “straight” photographs of an unusual kind, a hybridized form of direct observation, each with elements of presence and impresence.

The subjects are specific locations in Izbica, Piaski, Rejowiec, Krasnystaw, Bełżyce/Niedrzwica Duża, Trawniki, and Bełżec itself. In the six towns, I photographed in the town square, where the shop would likely have existed, the tracks where deportations occurred, the field or former open space (sometimes now overbuilt) beside the tracks, the area of the prison-ghetto as distinct from the transit camp, and in the case of Izbica, Piaski and Rejowiec, the site of the destroyed Jewish cemetery (admittedly not a part of Karski’s account but generally a key location in the history of the Holocaust as it played out in every town). Bełżec itself is unusual in the geography of memory: it is the only former camp to be completely covered by a memorial, or nearly completely (the railroad tracks are outside the gate). A massive boulder field extends over the footprint of the camp, whose stones change color subtly to indicate the site of the mass graves, with a memorial cut into its interior, inscribed with the biblical cry “Earth, do not cover my blood!” (Job 16:18). Around its perimeter is a walkway marked chronologically with the names towns from which each transport departed, in Yiddish and in Polish. At the entrance to the memorial complex is the museum describing the history and operation of the camp.

Among all the texts, photographs, objects and displays in the museum at Bełżec, a single voice echoes quietly through the space—Karski’s, from a video excerpt of his interview with Lanzmann, continuously looping. To paraphrase the philosopher Avishag Zafrani, it is a voice in and out of the past, tracing a a crest line between history and memory, generating a prophetic sense of things, if not a view.

Bełżec, Poland, museum display with video of Jan Karski

Zamość/Paris/Atlanta, 2025