It is already over twenty-five years since I lived in Detroit––twenty-five years since the deepest depression of my life, which coincided with the struggle really to commit myself to the risks of living as an artist. Perhaps it was coincidental that the inner struggle was played out in Detroit, America’s most notorious failed city, but there is no question that I found some respite from my internal darkness in photographing my way through the city’s abjection—a city full of empty fields that begged the very question of what a city was. Detroit was the city of my in-laws, good people who never managed to make me feel at home with them. In retrospect, it looks to me as if I turned to the city as a surrogate: if I were earnest enough, maybe it might extend itself to me? I learned the city hungrily, driving all of its neighborhoods in all seasons and all times of day and night. I read books and tried to grasp the collapse.

In an old notebook from that time, I find this entry:

The obvious: the white owning class and the white middle class abandoned Detroit, each for its own reasons––the former basically for profit and the latter from racist fear. The catastrophe of Detroit is a case study in the predatory logic of American greed and meanness, the bully game of the rich beating up on the most vulnerable in the society to win the political support of working and middle class whites who are a few rungs above African America in the social and economic hierarchy.

The city never did adopt me. When I left Detroit in 1996 to return home to California and begin graduate school at Stanford, I took a few hundred sheets of 35mm negatives with me, having printed virtually none of them when I lived there, and without a conviction that I would print them later. I never did print them. The next time I made photographs in Detroit, a single afternoon in the autumn of 2009, I ended the day with many rolls of medium format film in my pocket, and again printed virtually none of them. It was the same story in 2016, when I photographed in Detroit for the first time in color. I made scores of pictures which have been sitting in hard drives.

The obvious: the white owning class and the white middle class abandoned Detroit, each for its own reasons––the former basically for profit and the latter from racist fear. The catastrophe of Detroit is a case study in the predatory logic of American greed and meanness, the bully game of the rich beating up on the most vulnerable in the society to win the political support of working and middle class whites who are a few rungs above African America in the social and economic hierarchy.

The city never did adopt me. When I left Detroit in 1996 to return home to California and begin graduate school at Stanford, I took a few hundred sheets of 35mm negatives with me, having printed virtually none of them when I lived there, and without a conviction that I would print them later. I never did print them. The next time I made photographs in Detroit, a single afternoon in the autumn of 2009, I ended the day with many rolls of medium format film in my pocket, and again printed virtually none of them. It was the same story in 2016, when I photographed in Detroit for the first time in color. I made scores of pictures which have been sitting in hard drives.

Perhaps the problem is that the city overwhelms photography––that its suffering breaks the frame, refuses the impulse to hold it close. Or perhaps the problem is that the city overwhelms me, exceeds my emotional capacity to solve it for images, or triggers an awareness of psychic turbulence still somehow unhealed, which I came to associate with the city.

In a notebook from 2016, I wrote this:

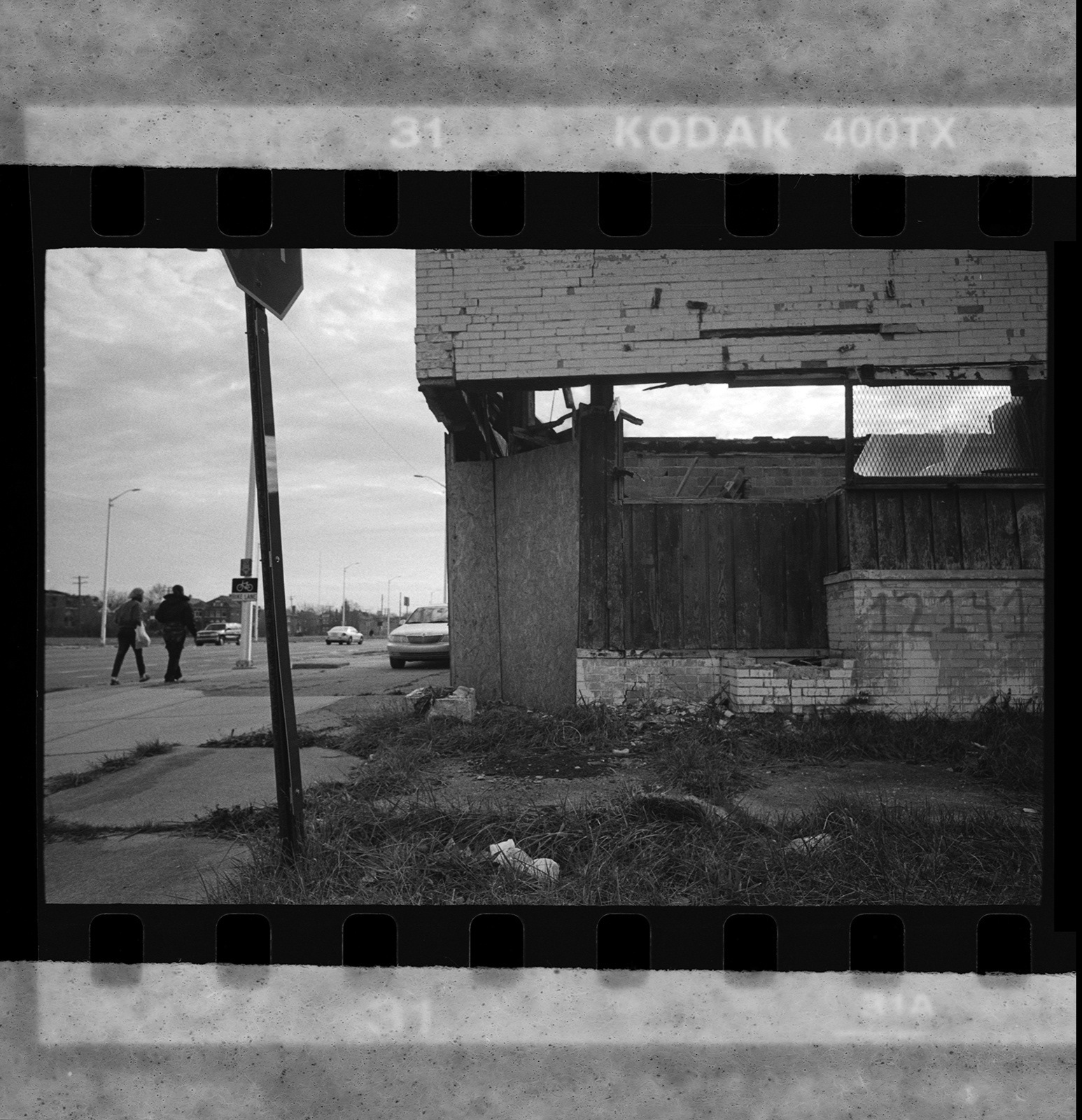

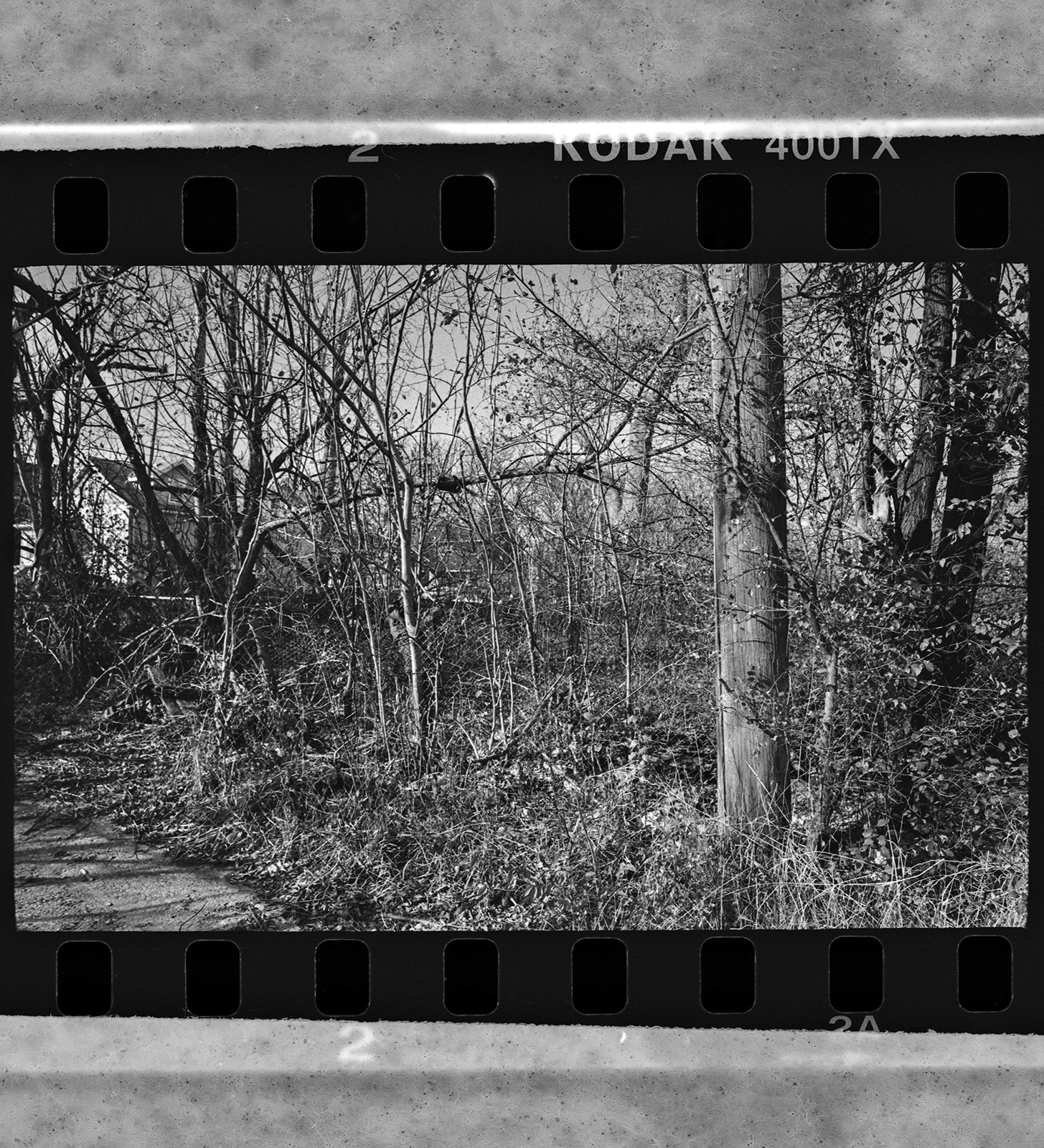

The point of photographing in Detroit is not to feed by-now cliched images of spectacular ruin, but to receive Detroit fairly––as a site of mourning for the savagery and losses of postwar American capitalism. It is the non-spectacular ruination of Detroit that is the most important part of its urban geography––the strange aftermath of the social violence unleashed over decades on the city. Me, it’s not that I want to reduce Detroit to its ruins––I don’t deny the innovation and grit of many Detroiters, evident in some parts of the city. But the “revival” along the Woodward corridor, I wouldn’t call it a revival, rather a highly selective reinvestment. Revival––undoing the vast regions of the city’s blight––is lifetimes away for Detroit.

In a notebook from 2016, I wrote this:

The point of photographing in Detroit is not to feed by-now cliched images of spectacular ruin, but to receive Detroit fairly––as a site of mourning for the savagery and losses of postwar American capitalism. It is the non-spectacular ruination of Detroit that is the most important part of its urban geography––the strange aftermath of the social violence unleashed over decades on the city. Me, it’s not that I want to reduce Detroit to its ruins––I don’t deny the innovation and grit of many Detroiters, evident in some parts of the city. But the “revival” along the Woodward corridor, I wouldn’t call it a revival, rather a highly selective reinvestment. Revival––undoing the vast regions of the city’s blight––is lifetimes away for Detroit.

From the fall of 2016, when my daughter Miriam began to study at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, I made a point of going into Detroit on my visits to see her. Often I would return to the same neighborhoods I already knew from the nineties, sometimes making black and white 35mm pictures and sometimes color digital photographs. In 2020 I started looking into the collected pictures, with the thought of a sequence contemplating the almost rural, decidedly anti-bucolic post-urban realities of Detroit. I set about scanning the black and white film, and it seems fitting enough not to crop out the masking tape holding the film down, as if to leave in the bandages. Now I find myself making a set of pictures for this website––which is to say, for the unsatisfying concentration that websites allow. And why this work now?

Miriam was born while I was still in graduate school, two years after leaving of Detroit. She has just graduated with highest honors from the English department, with a thesis given the department's highest award. Her work studies race, class, gender, urban redesign and architecture in postwar Detroit as these appear in the novels of Jeffrey Eugenides; a key resource for her is the work of the Holocaust historian and memory studies theorist Michael Rothberg, particularly his most recent work on the "implicated subject." In the spring of 2020, Miriam writes:

Before I moved to Michigan, Detroit was a place that existed in photographs rather than reality: my grandmother as a

teenager in her prom dress, her face aglow from the light of a window in the apartment above the bar her father owned, or as a little girl, stoically recovering from chickenpox in a chair on the

front lawn. The house she grew up in, on a street near what became Edsel Ford Freeway, is probably gone in the same way Tessie’s house on Hurlbut is: hidden by weeds, changed beyond recognition, or lost through demolition. Like the Eugenideses and the Stephanideses, my grandparents moved to a suburb of Detroit. My great-great-grandmother raised twelve children in the city, and none of her descendants live there. What remains in those empty spaces whose fullness implication has disappeared? I think it’s memory, which is always located in places you can’t return to.

teenager in her prom dress, her face aglow from the light of a window in the apartment above the bar her father owned, or as a little girl, stoically recovering from chickenpox in a chair on the

front lawn. The house she grew up in, on a street near what became Edsel Ford Freeway, is probably gone in the same way Tessie’s house on Hurlbut is: hidden by weeds, changed beyond recognition, or lost through demolition. Like the Eugenideses and the Stephanideses, my grandparents moved to a suburb of Detroit. My great-great-grandmother raised twelve children in the city, and none of her descendants live there. What remains in those empty spaces whose fullness implication has disappeared? I think it’s memory, which is always located in places you can’t return to.

It seems that a sequence of photographs on Detroit is something I have held within myself for a lot of years, not knowing when or how it would emerge. And it seems also that it takes time and (new) generations to begin to understand how Detroit remains an activated state of lack—a lack that gives—and a site of American loss over which none of us know how to exert a claim.

May 2020