For my mother, ז״ל

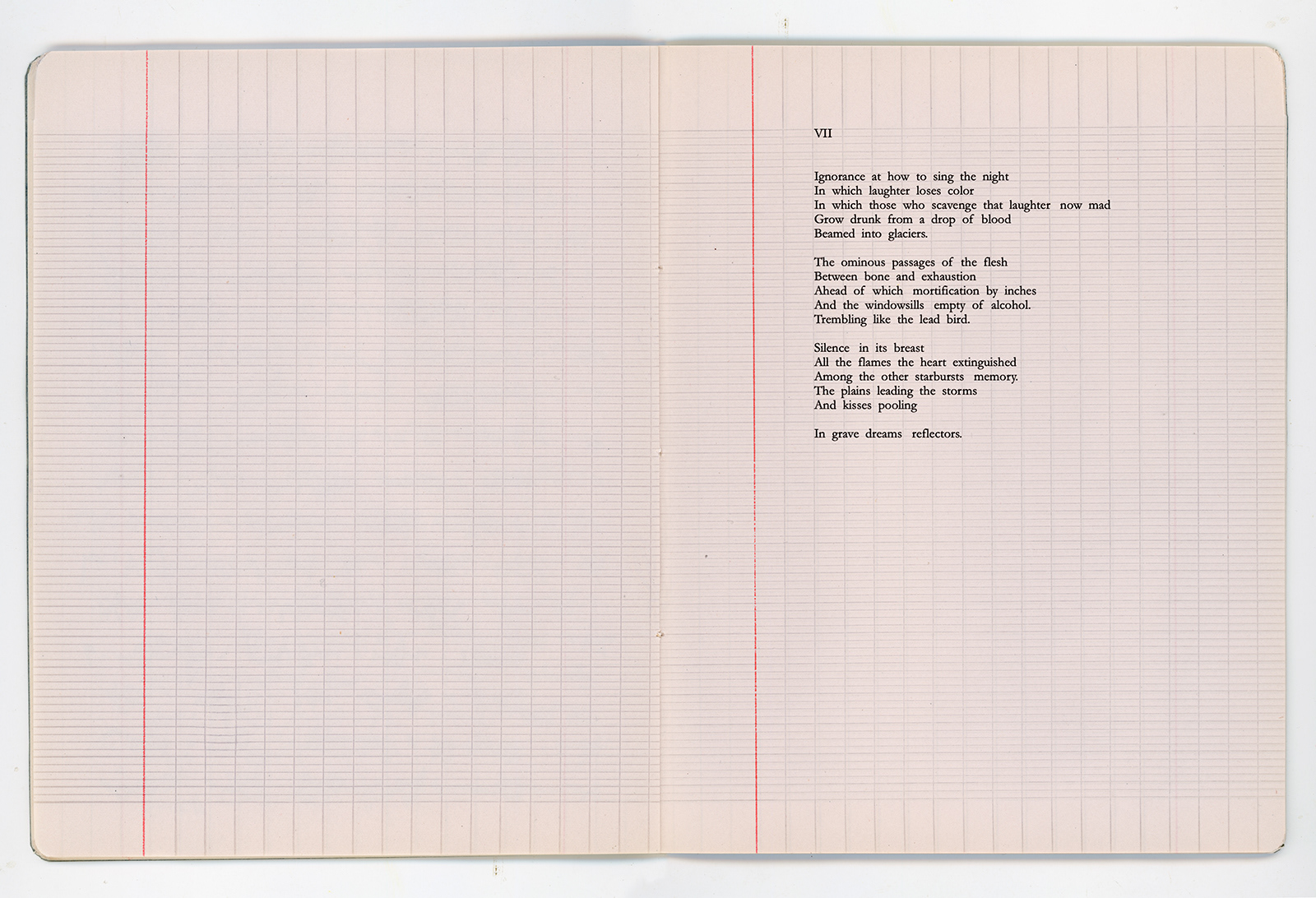

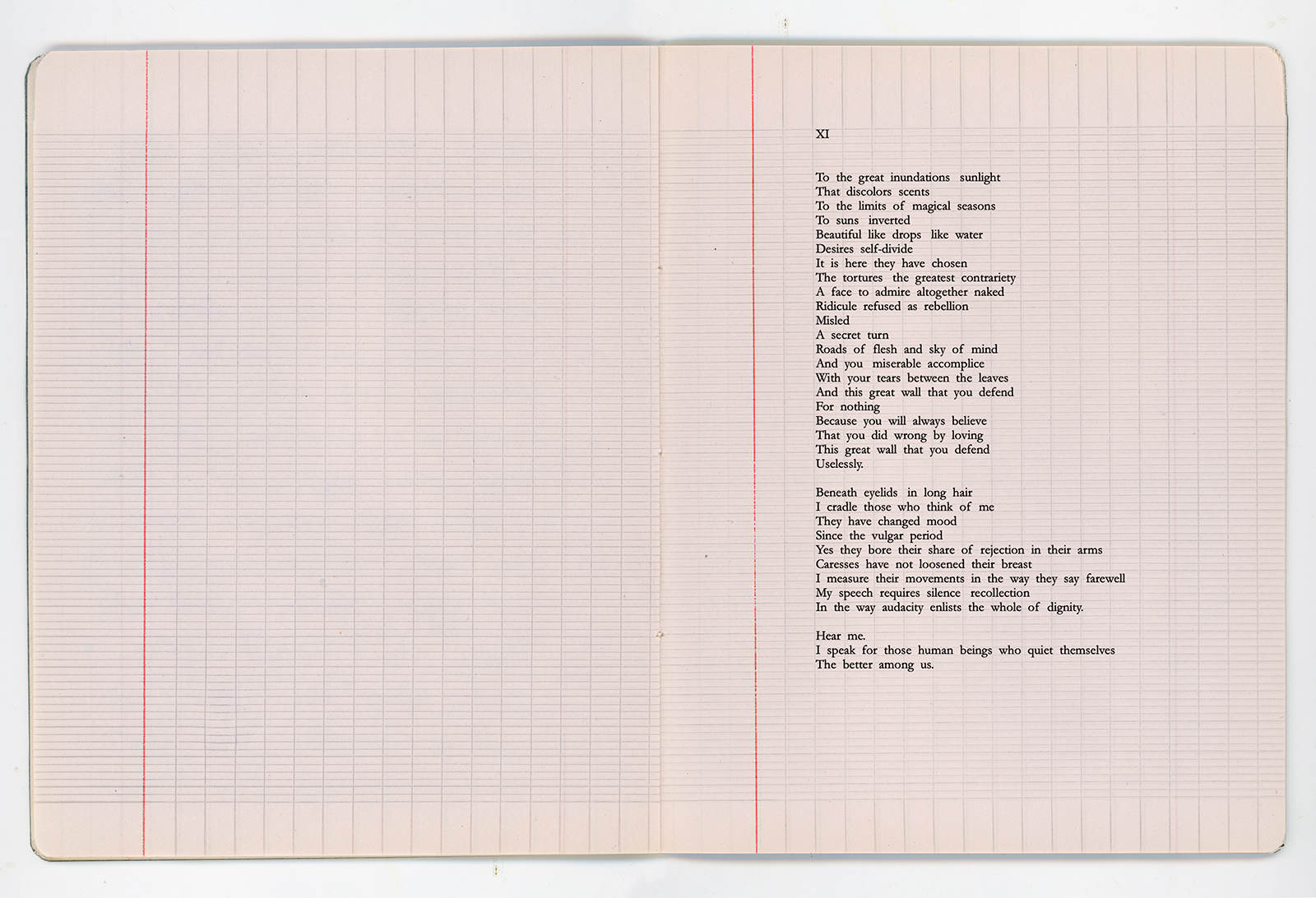

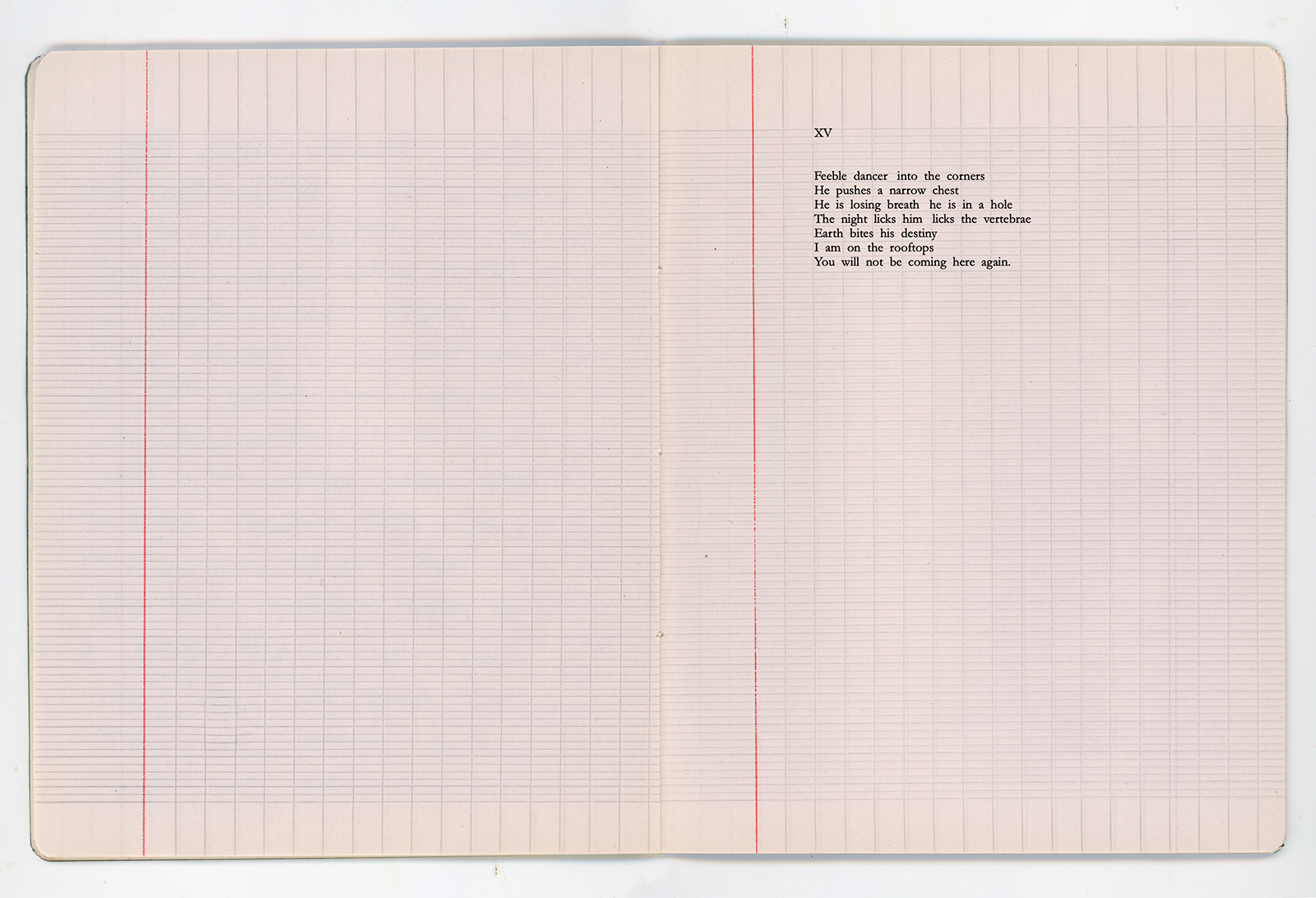

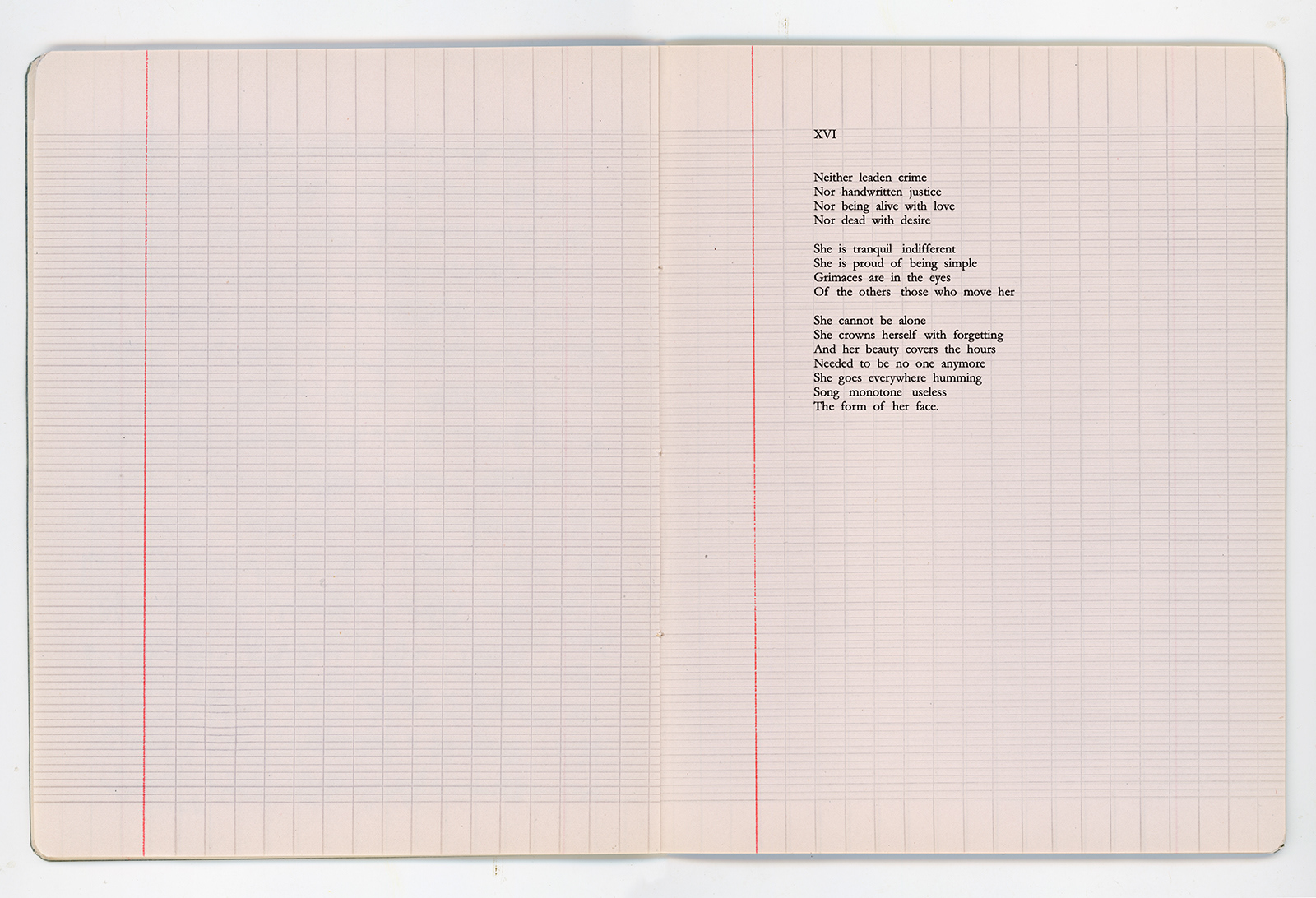

In the near aftermath of my mother’s sudden death in December 2024, seeking coherence for the intensity of grief, I found my way to Paul Eluard’s 1929 L’Amour la Poésie (Love, Poetry), a classic of twentieth-century French poetry. In particular, I kept returning to the book's second part, a cycle of twenty-two poems titled “Seconde nature” (“Second nature”). These poems seemed powerfully to mirror the simultaneous turbulence and density of my own inner states. They felt to me like a welcoming place for my mother’s presence within me—a presence with the force of her love and her sadness, both of these bound in the familiar ways, and also a presence seeking unexpected forms of luck, atonement, deviation, subversive forgetting. Perhaps most helpfully, the poems seemed to offer a feeling for how her neshomah or soul was already in the process of transforming itself, as if a glimpse into her own second nature. I decided to translate the poems, attempting to find English forms for their simultaneous terseness and freedom.

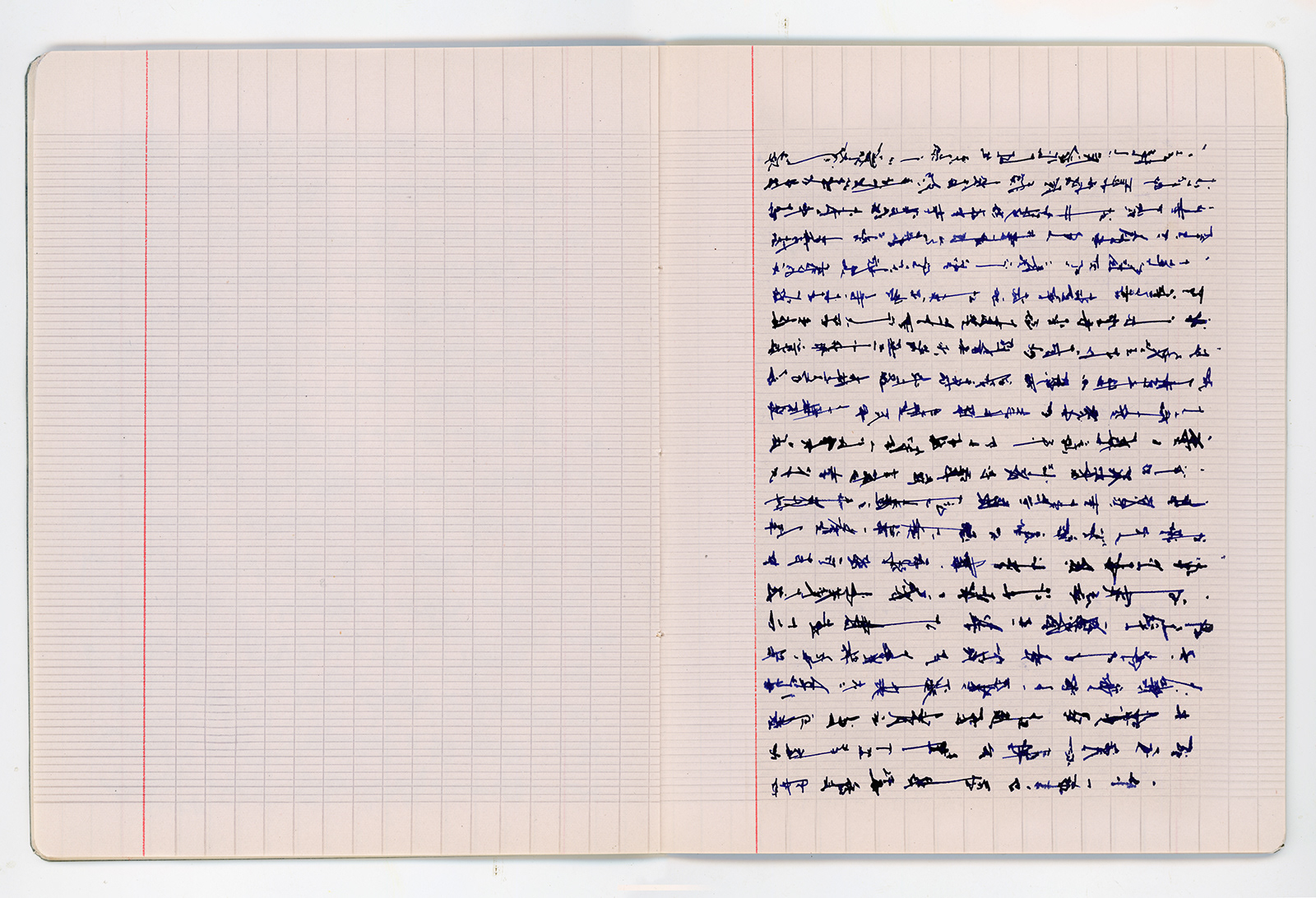

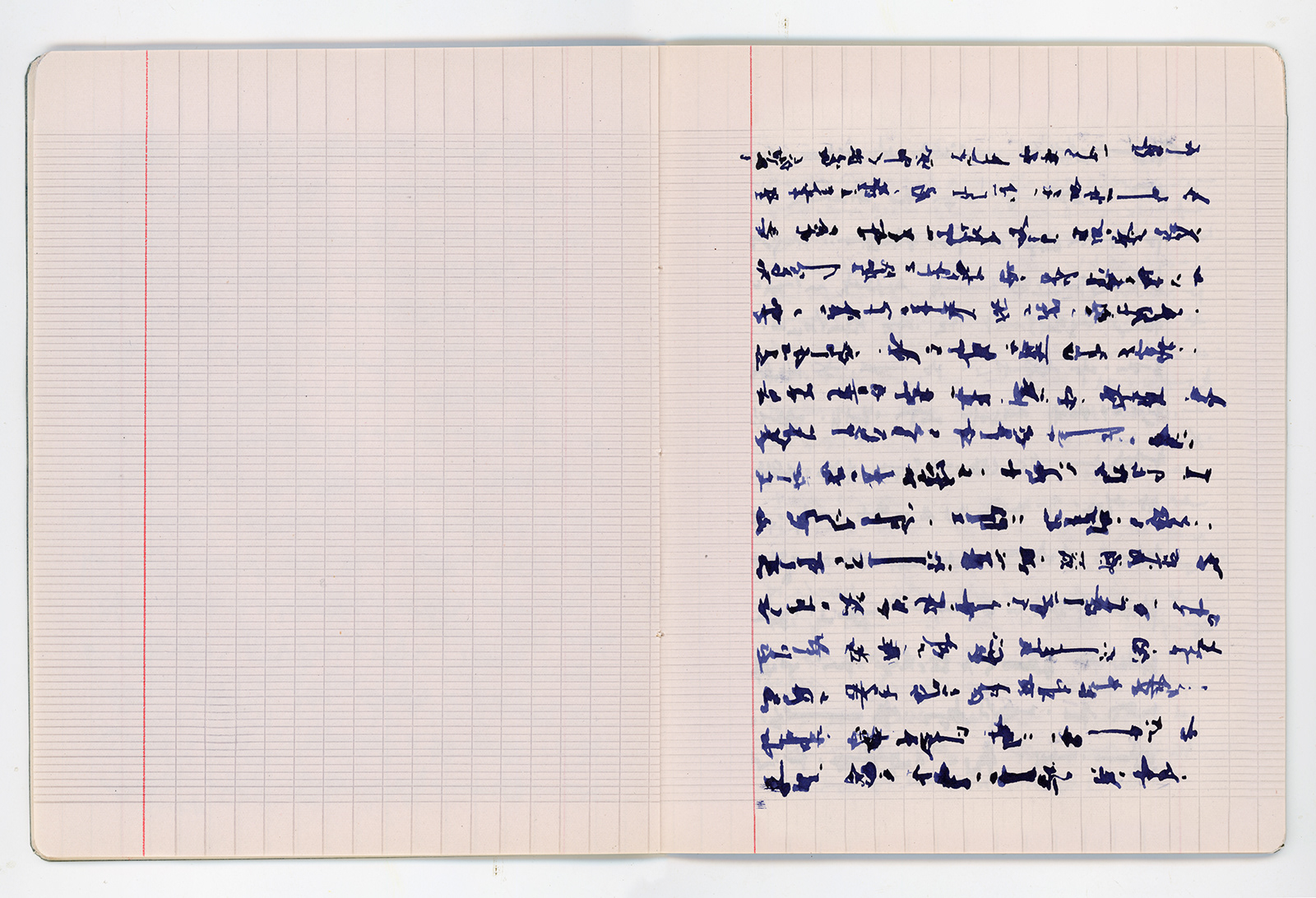

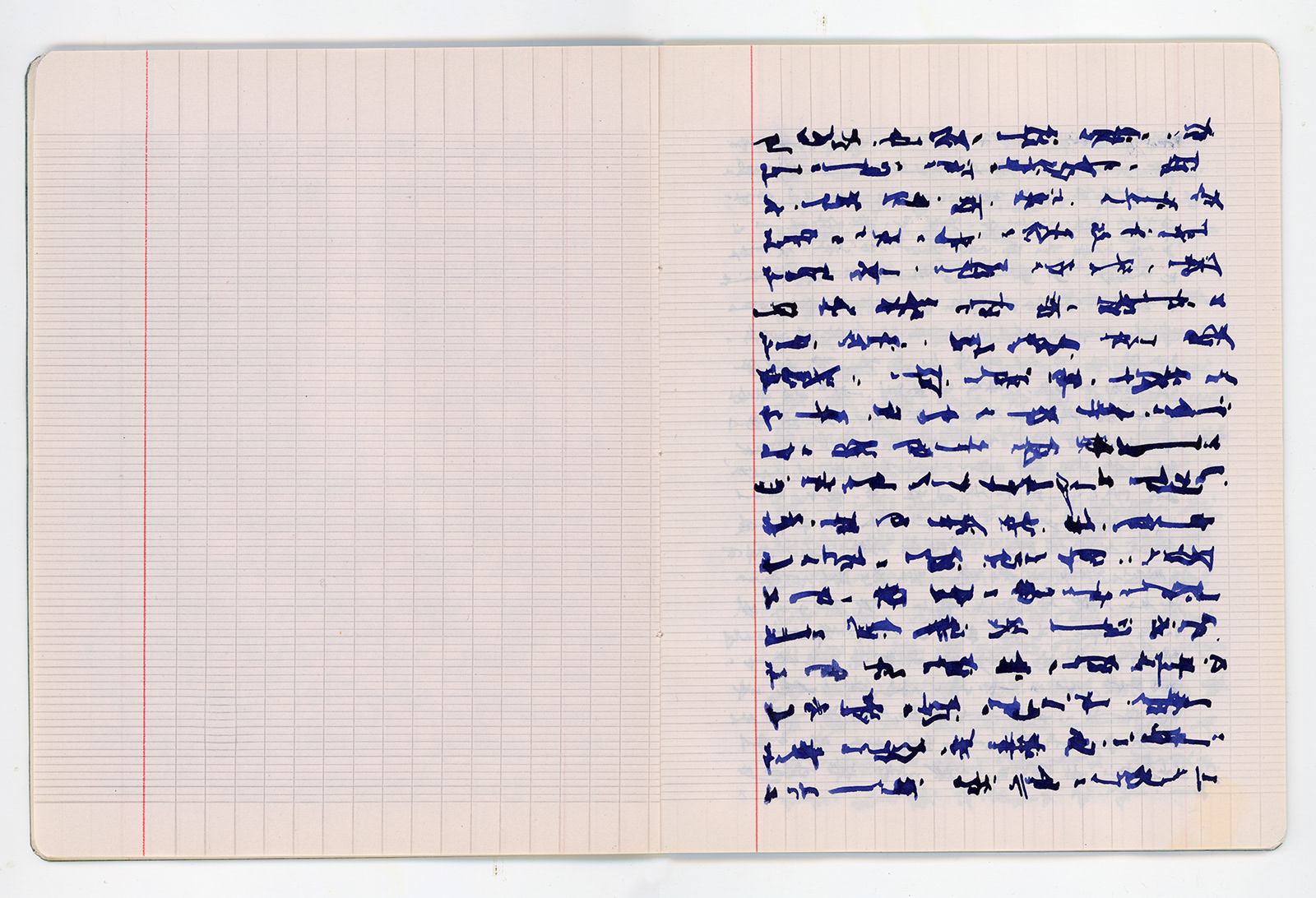

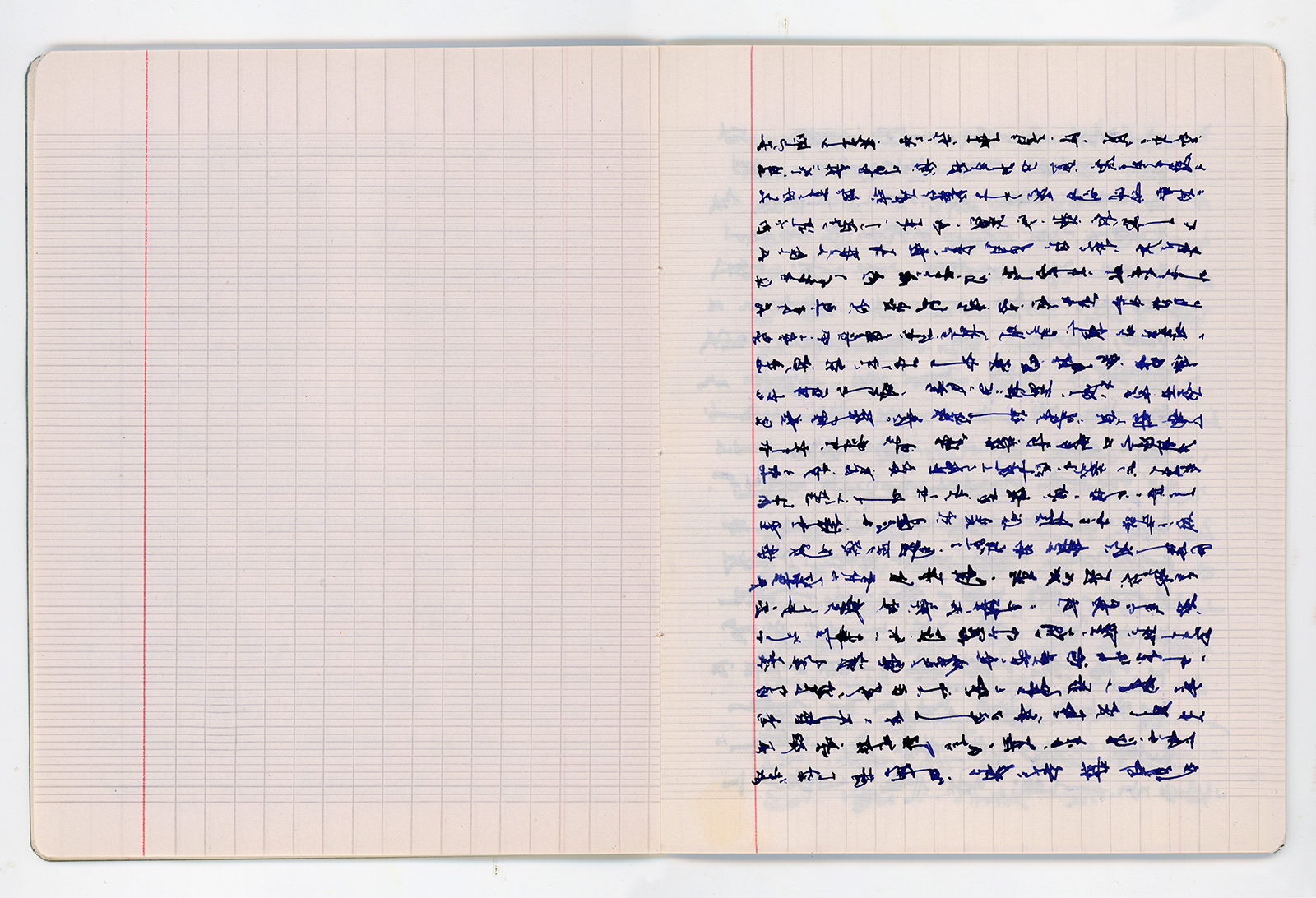

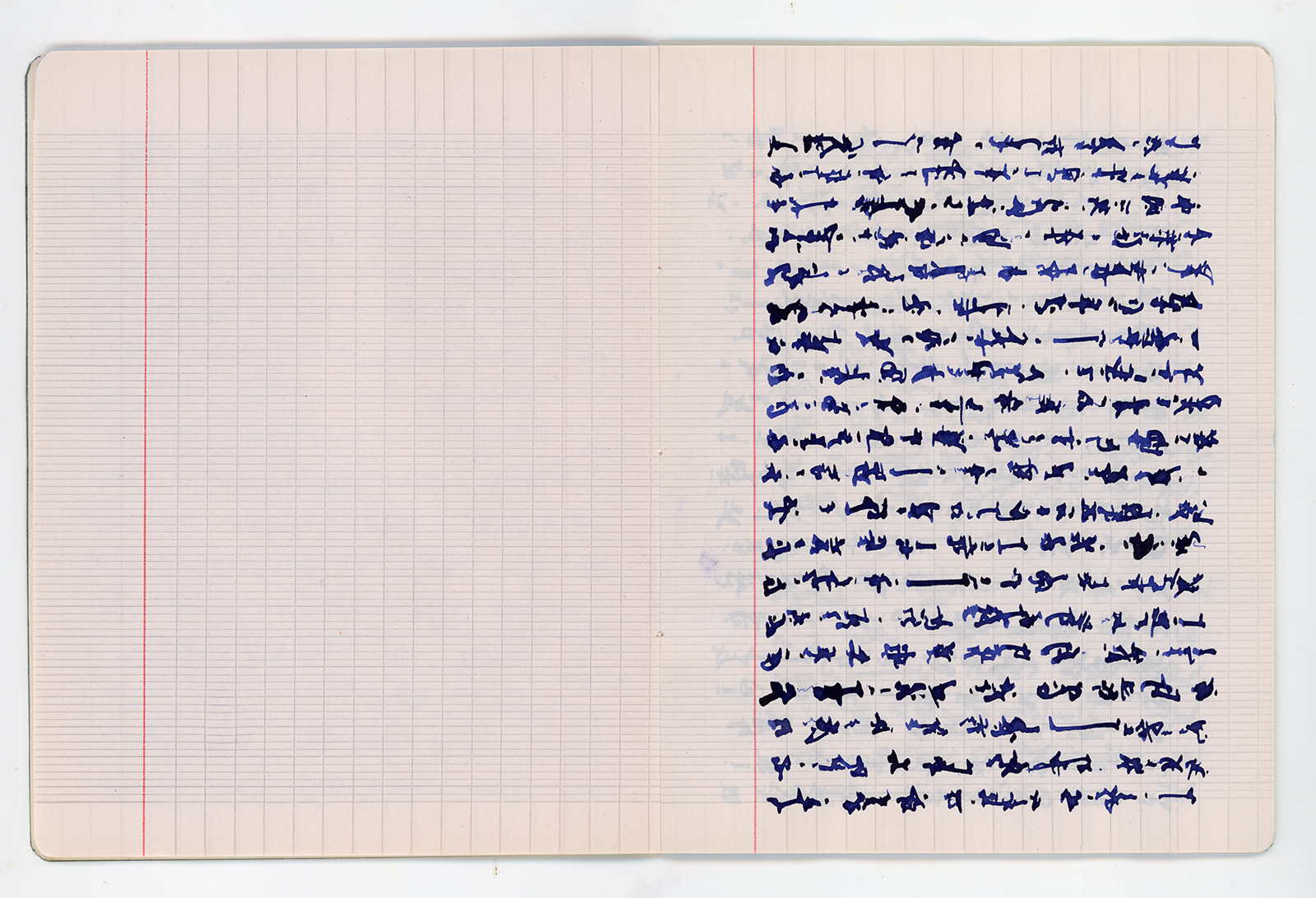

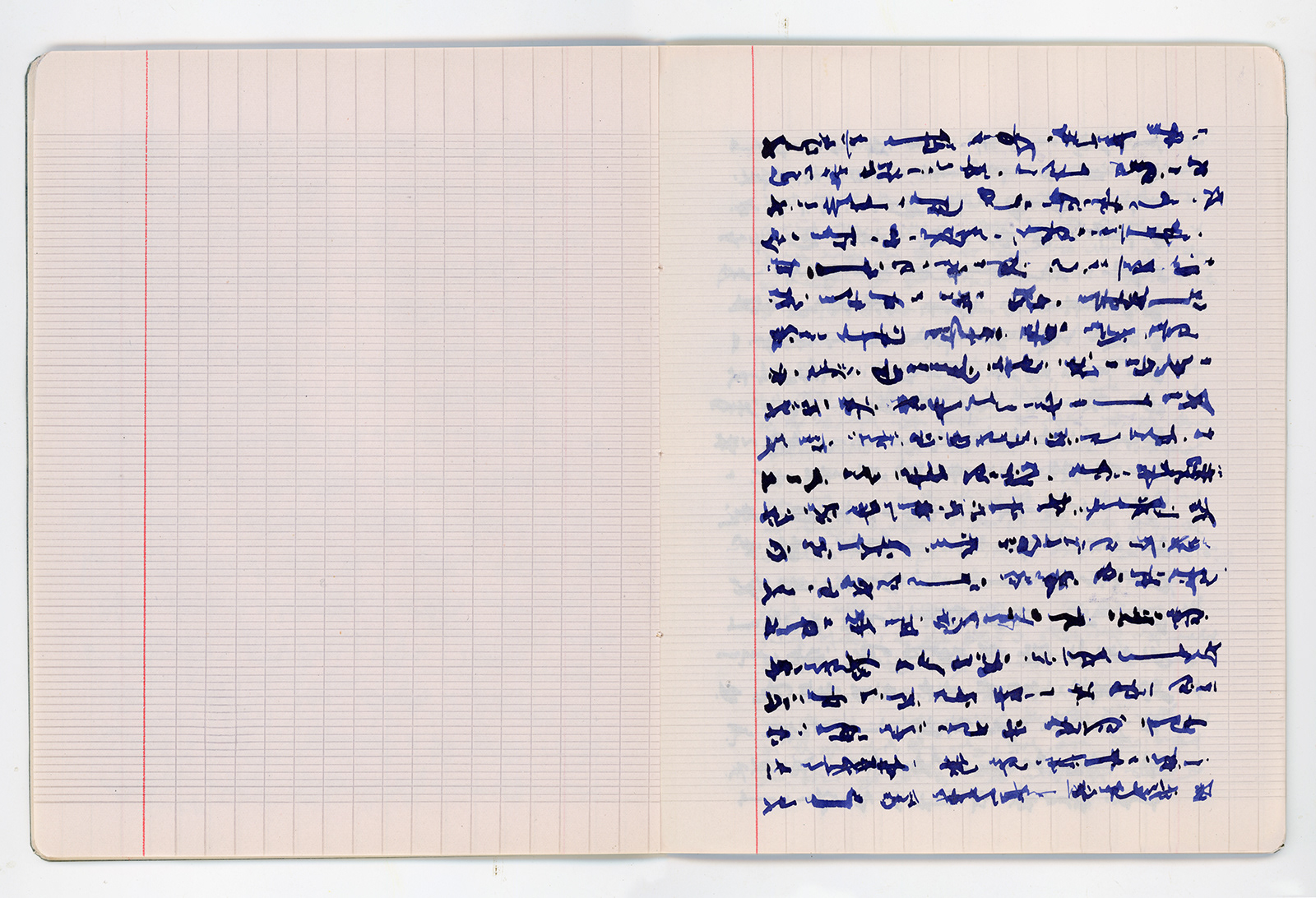

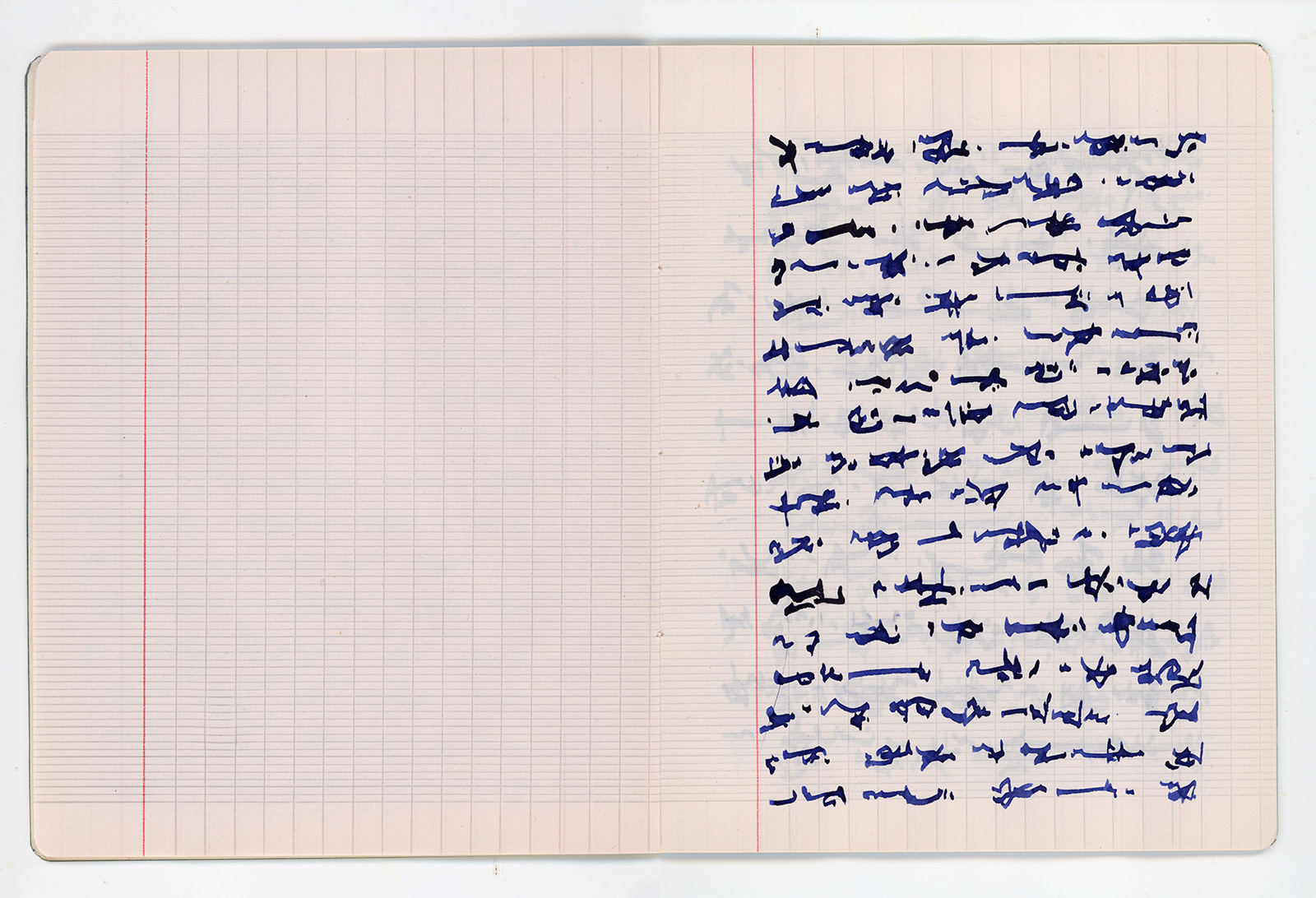

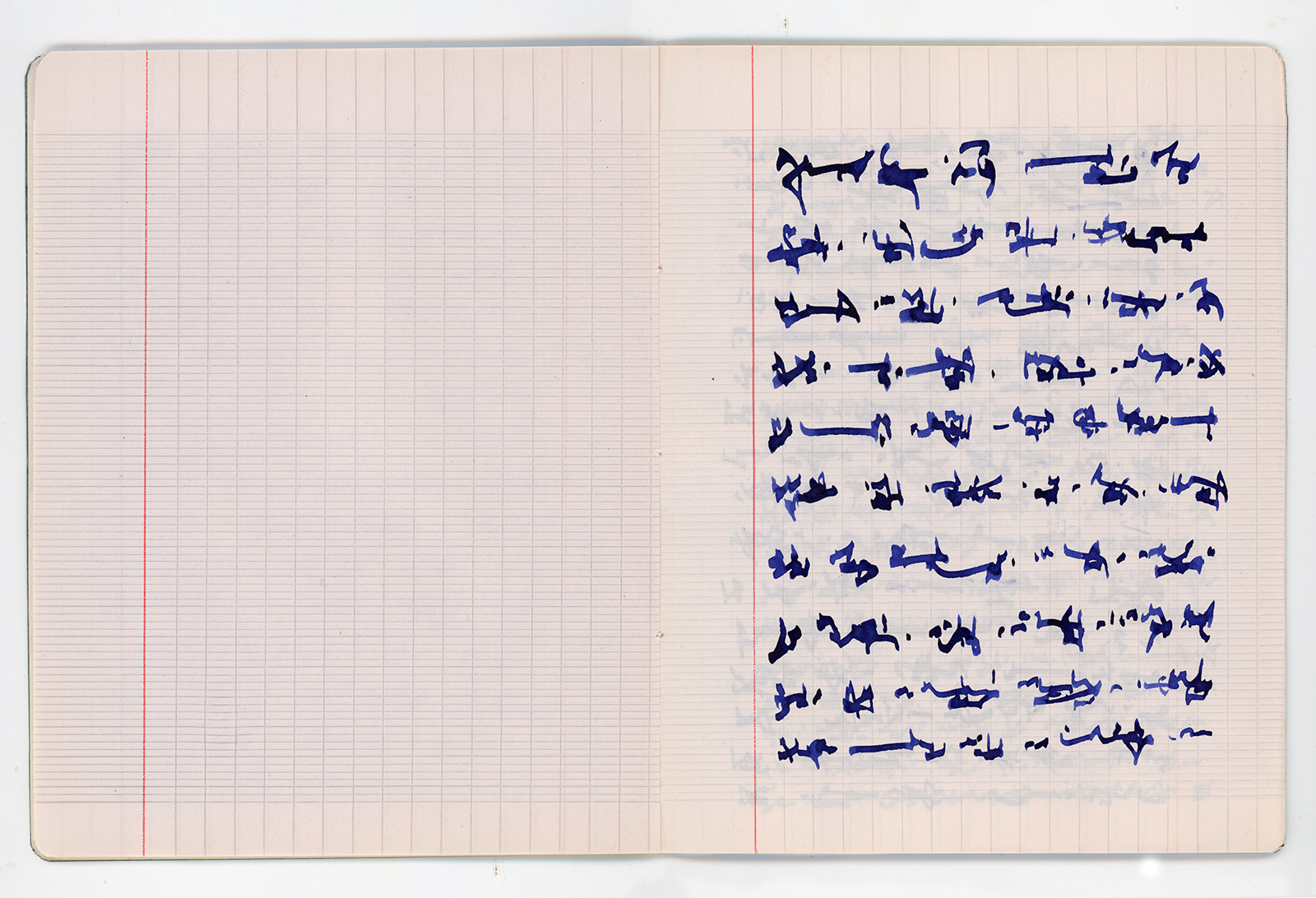

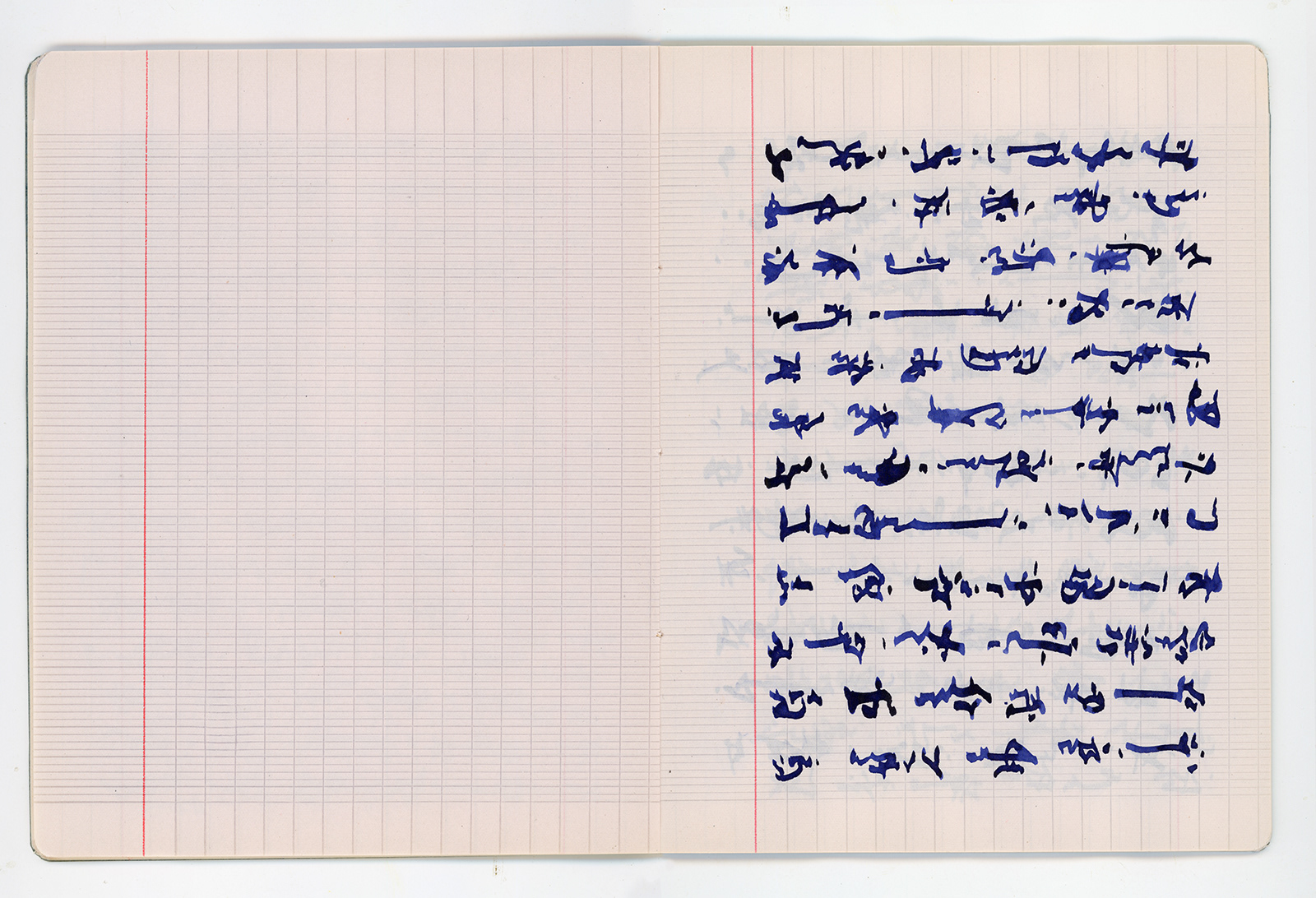

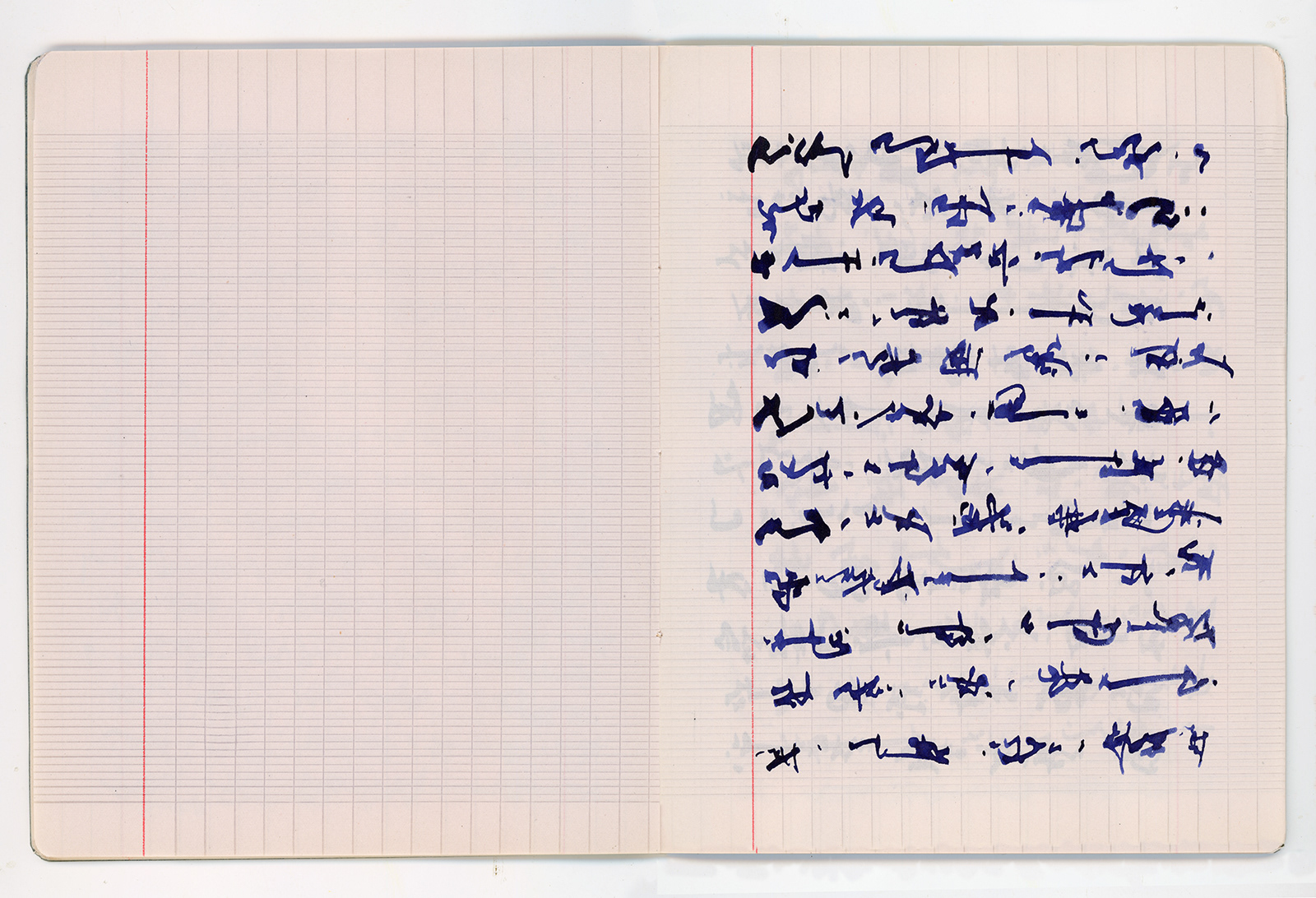

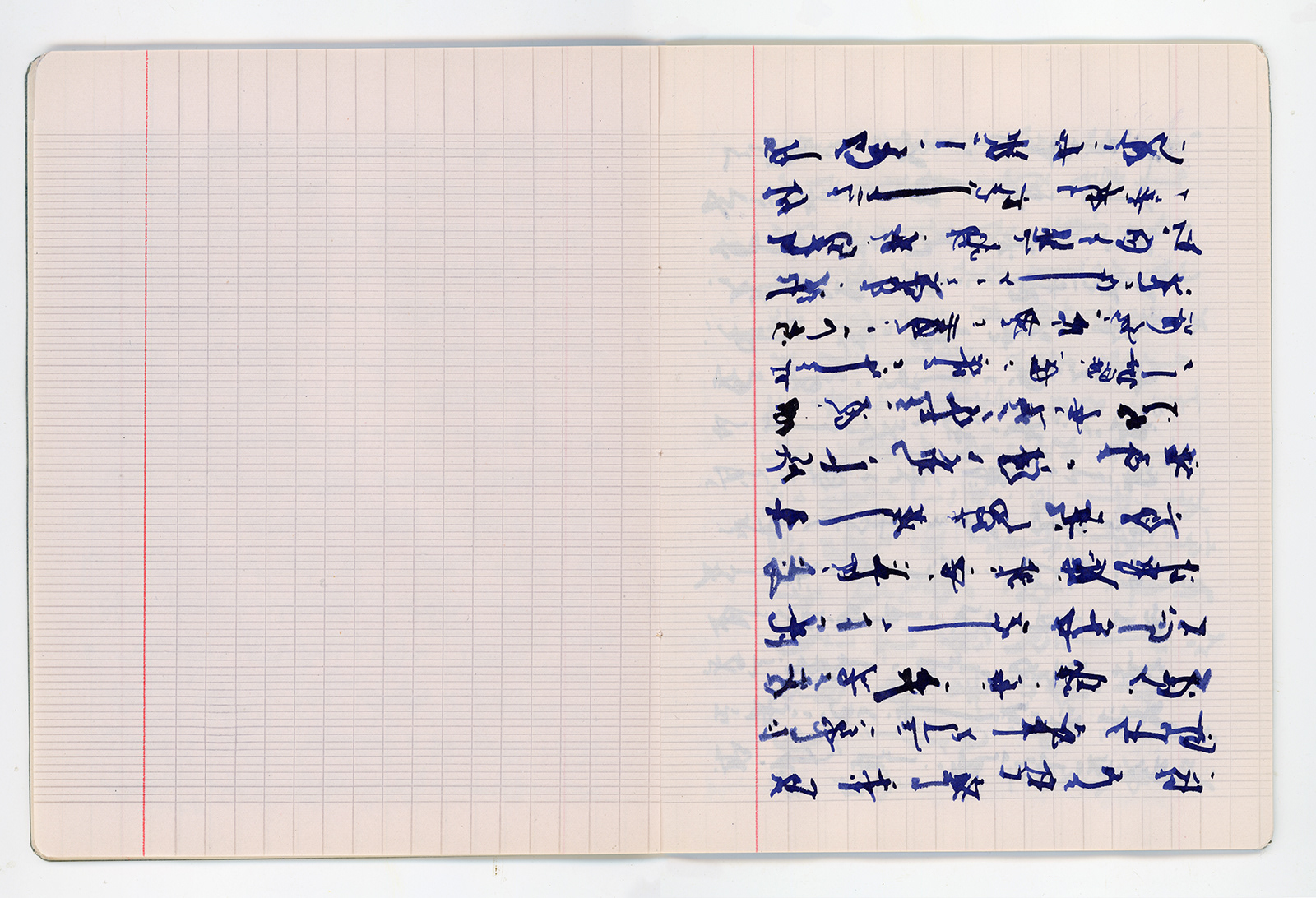

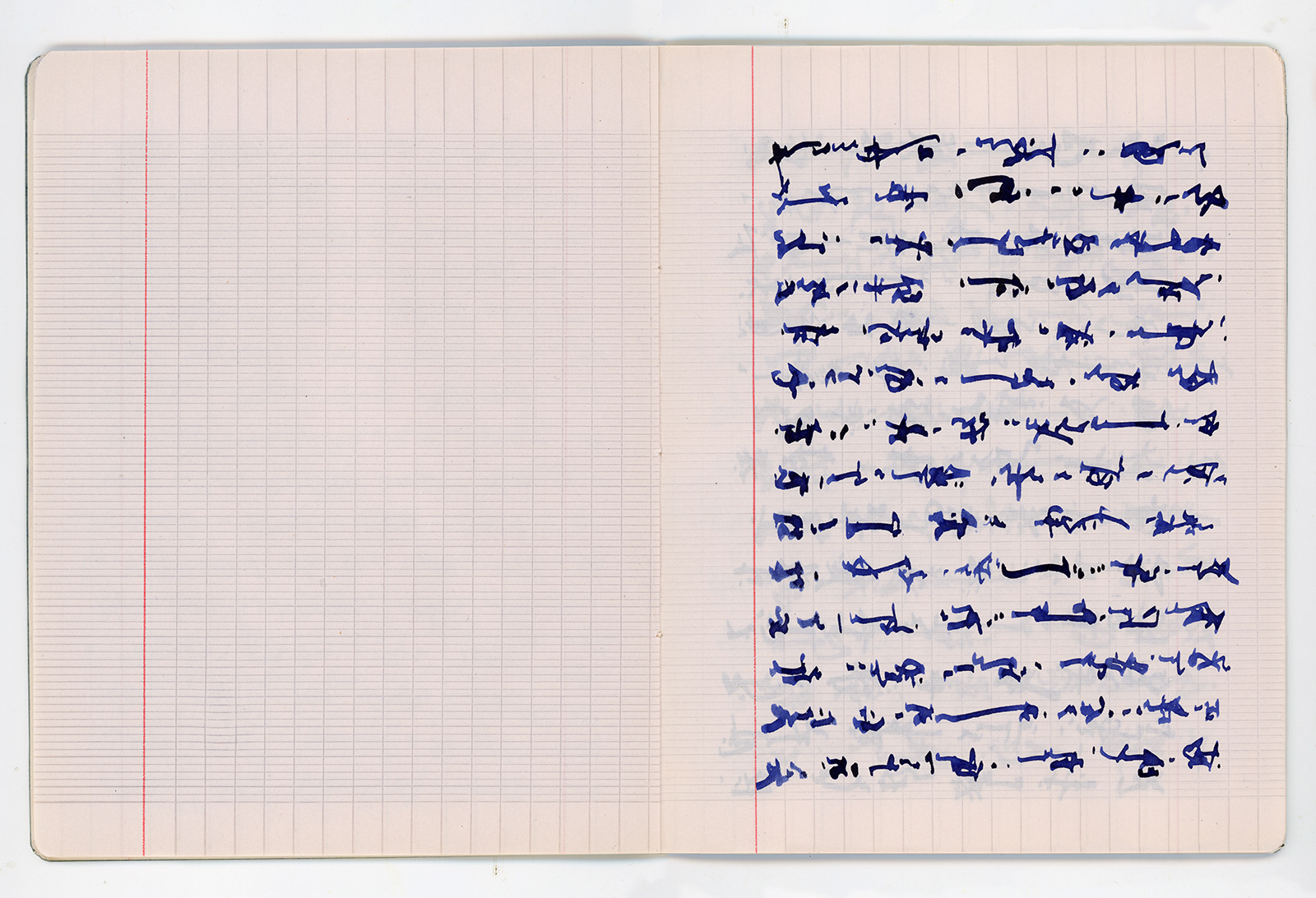

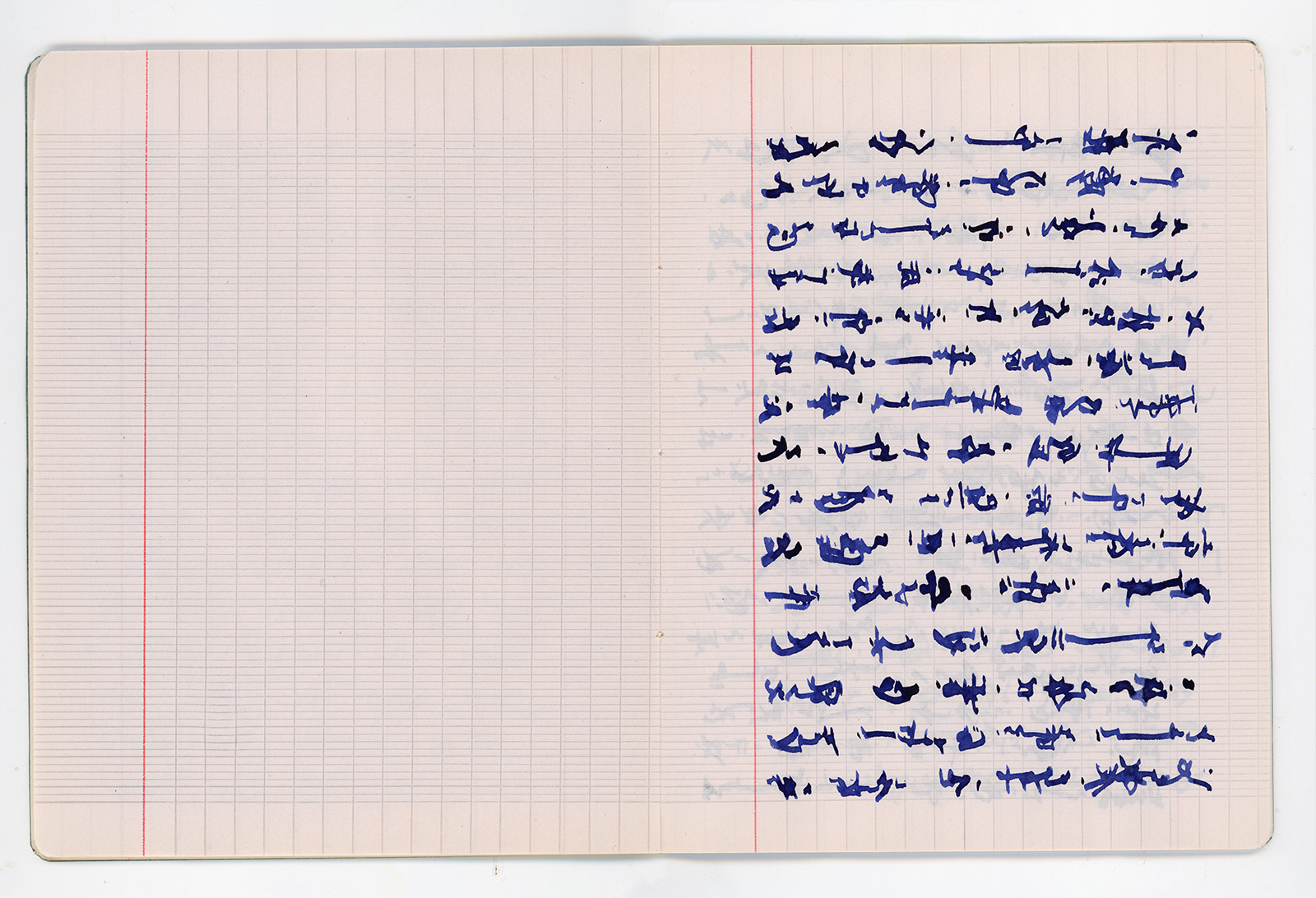

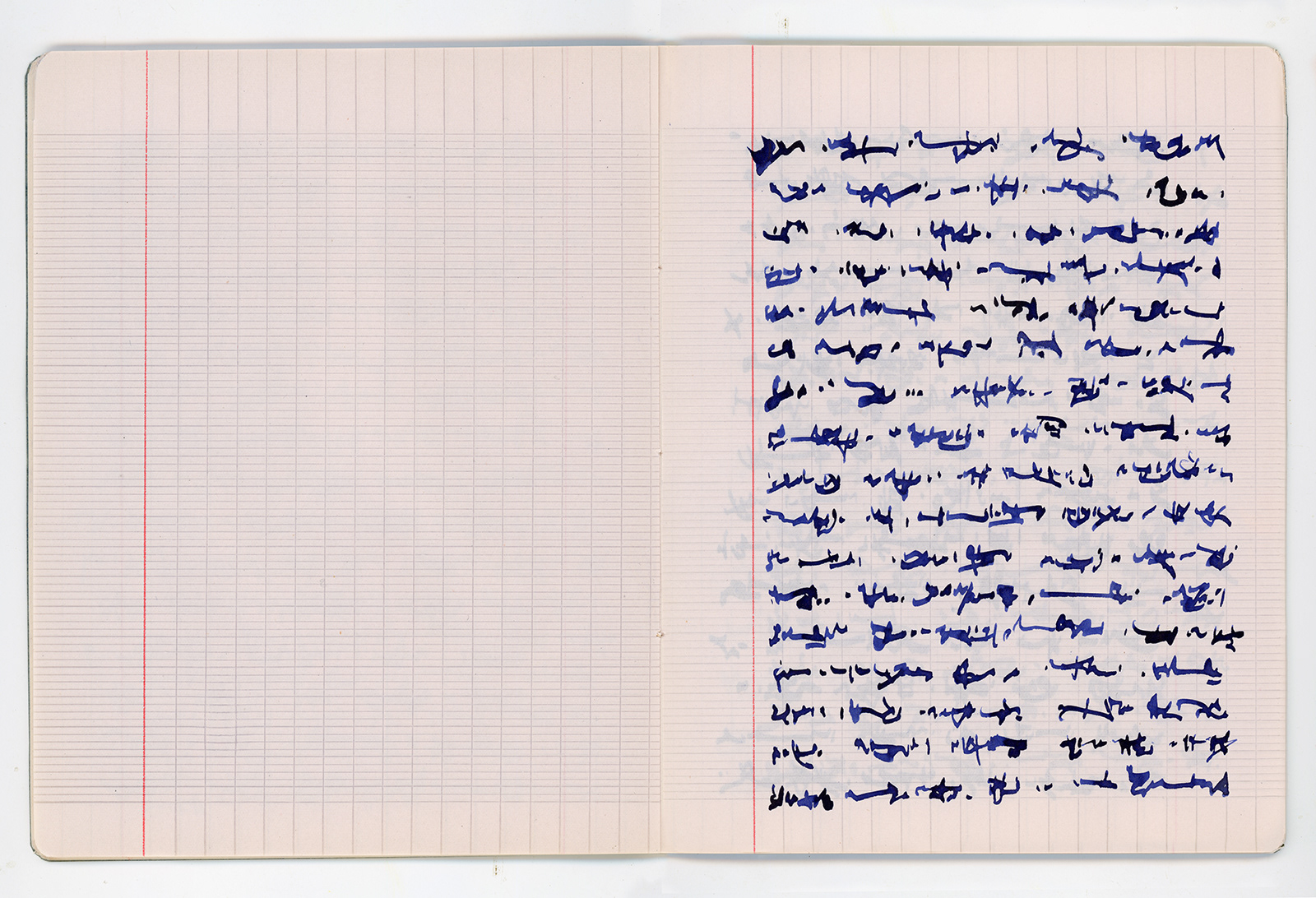

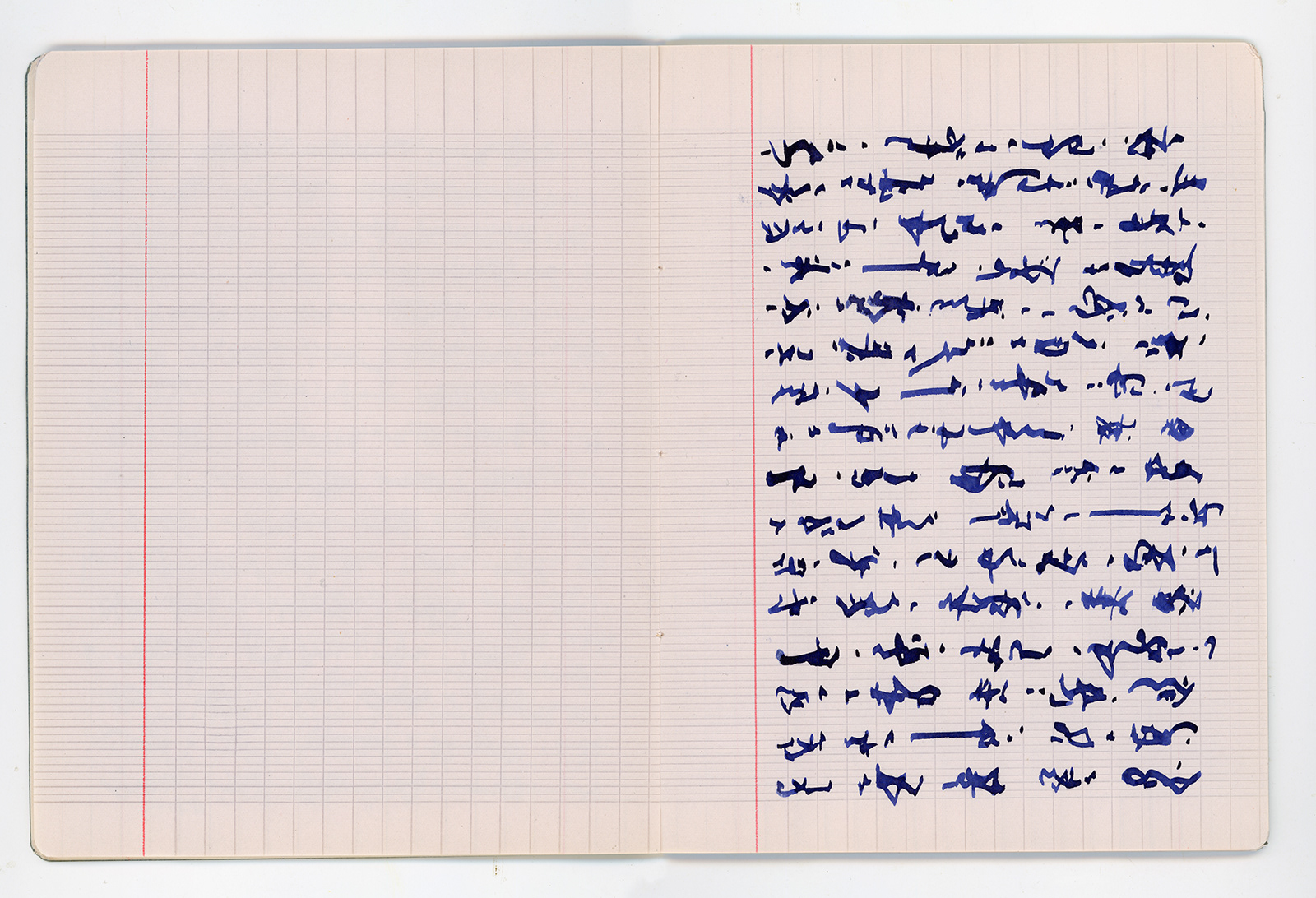

The work here combines these translations with a series of asemic writings I made in Paris half a year ago, in a humble notebook I found in a paper store. Notebooks like these, printed with a distinctive grid pattern, were used for decades to teach penmanship to French schoolchildren. It seemed a good match for the kind of drawing I was interested in—mark-making with letter-like qualities but without semantic content. In the wake of my mother’s death, these drawings reverberated with the not-quite-sayable aspects of rupture, and also with Eluard’s restive poems.

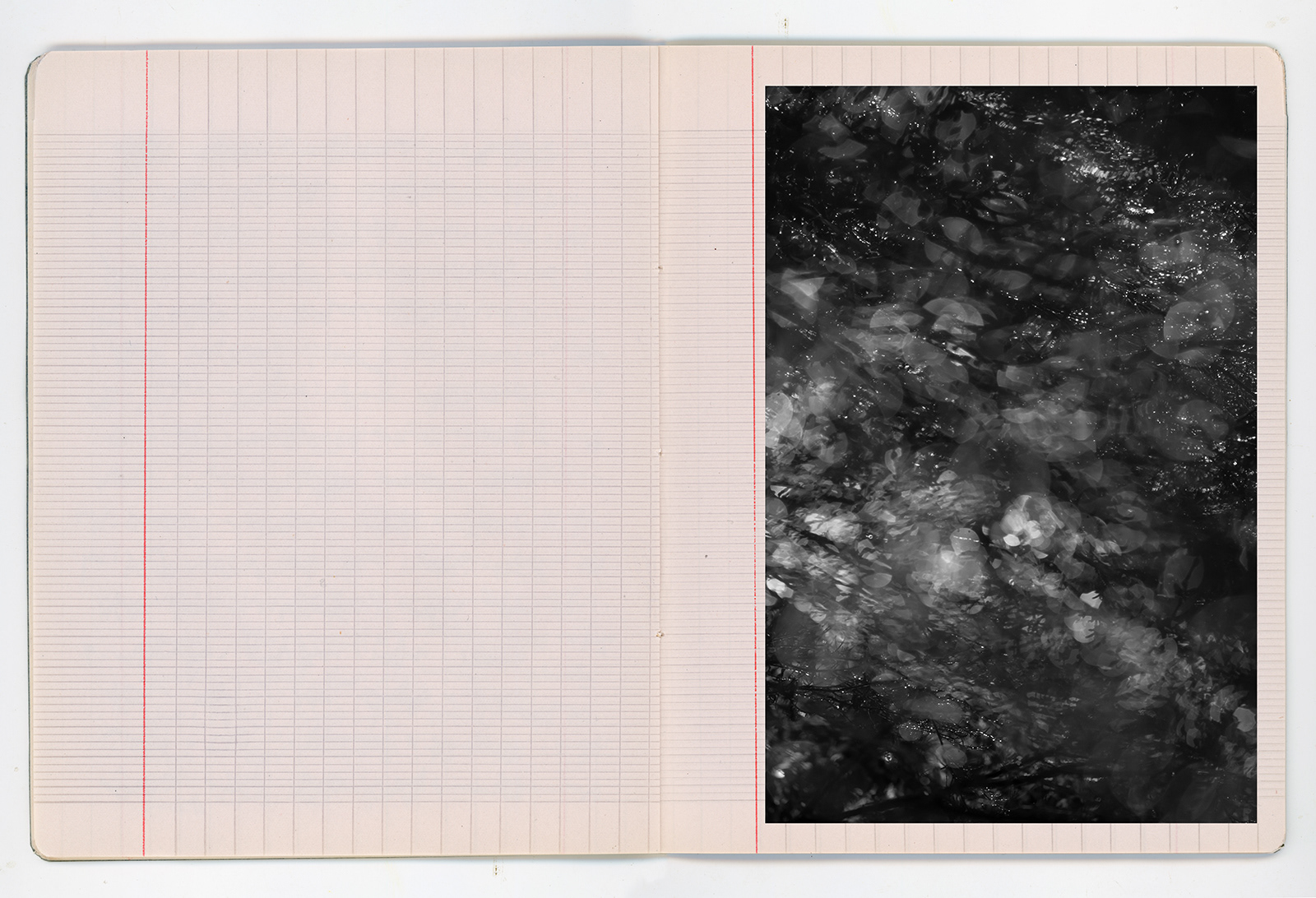

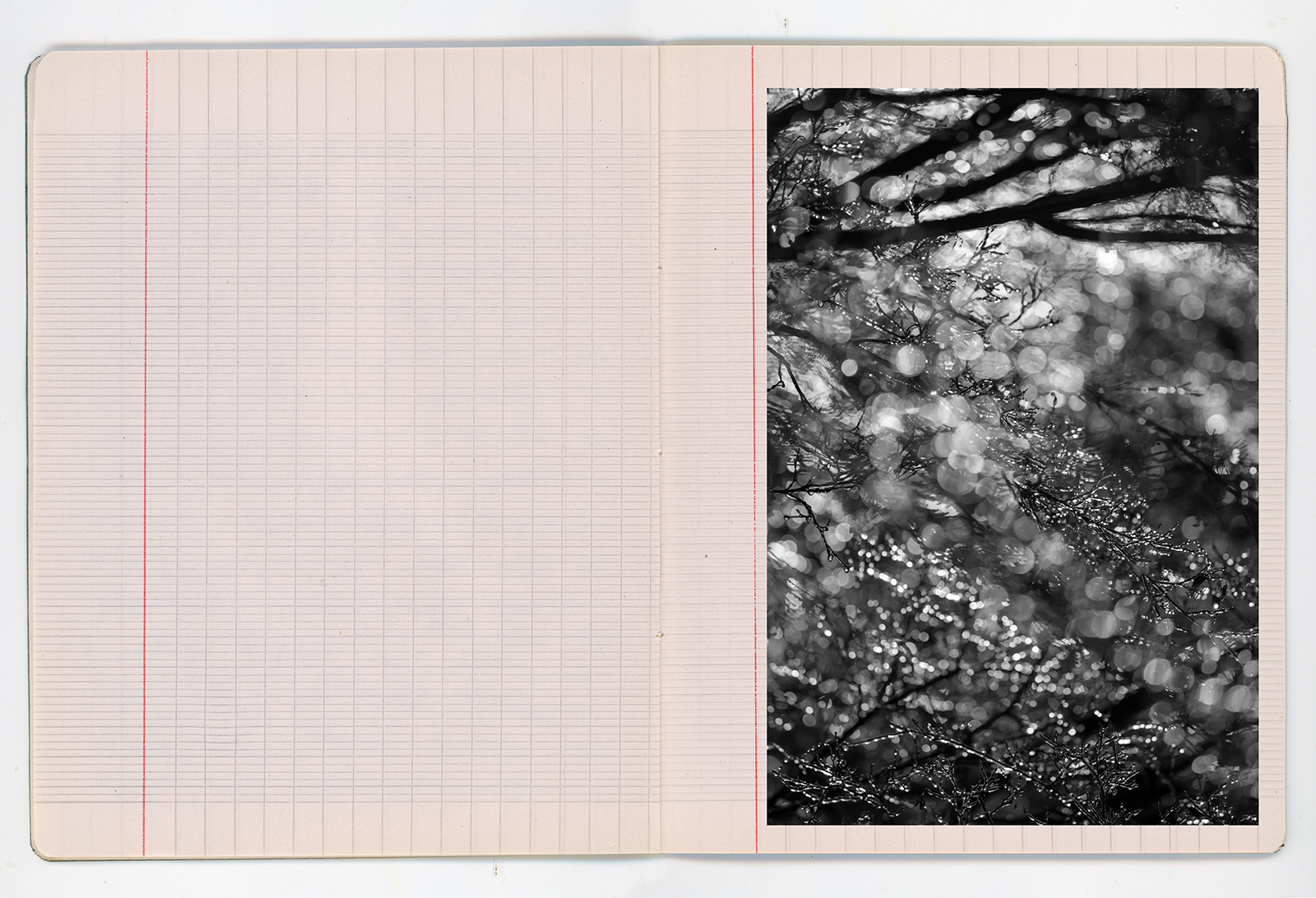

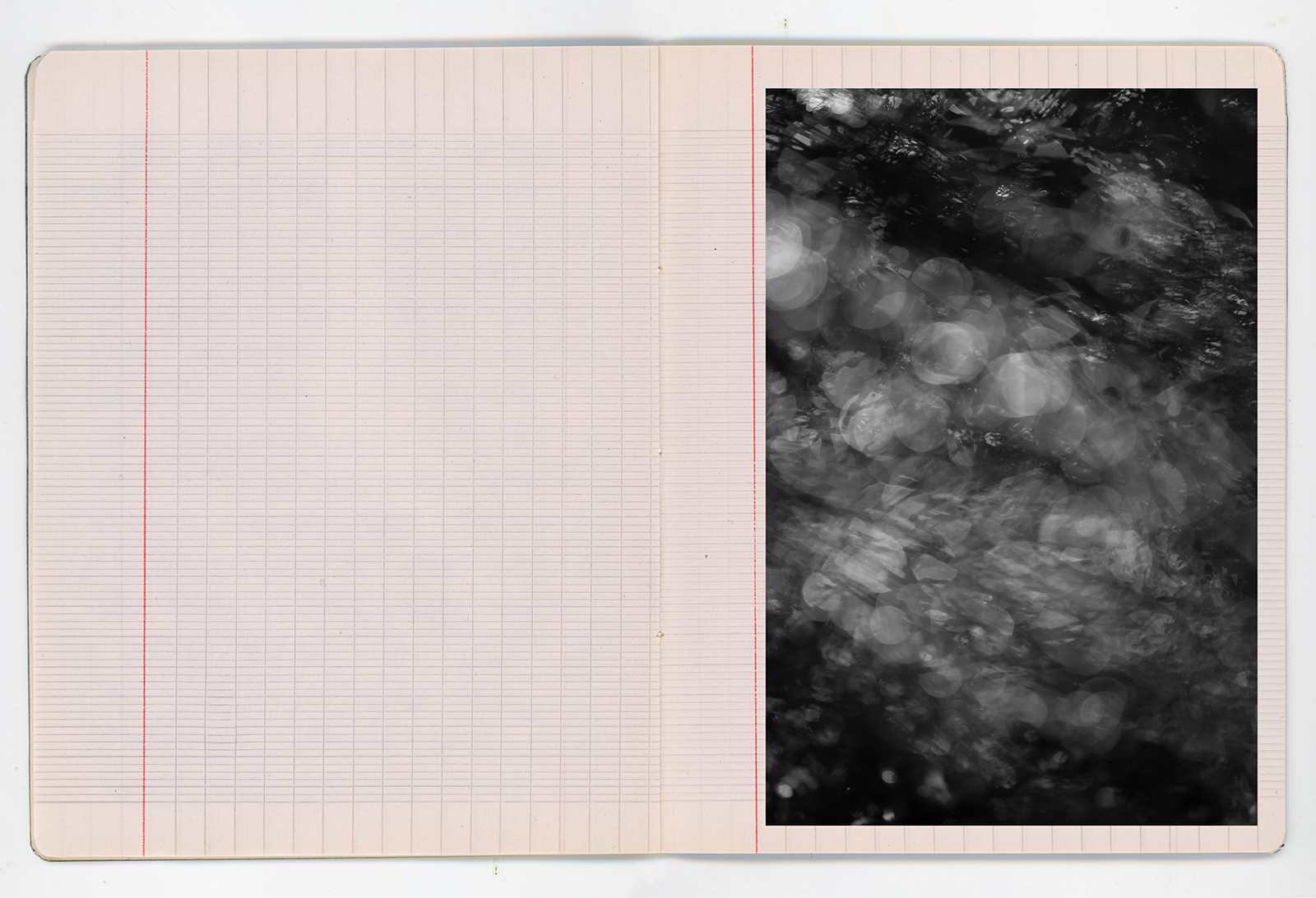

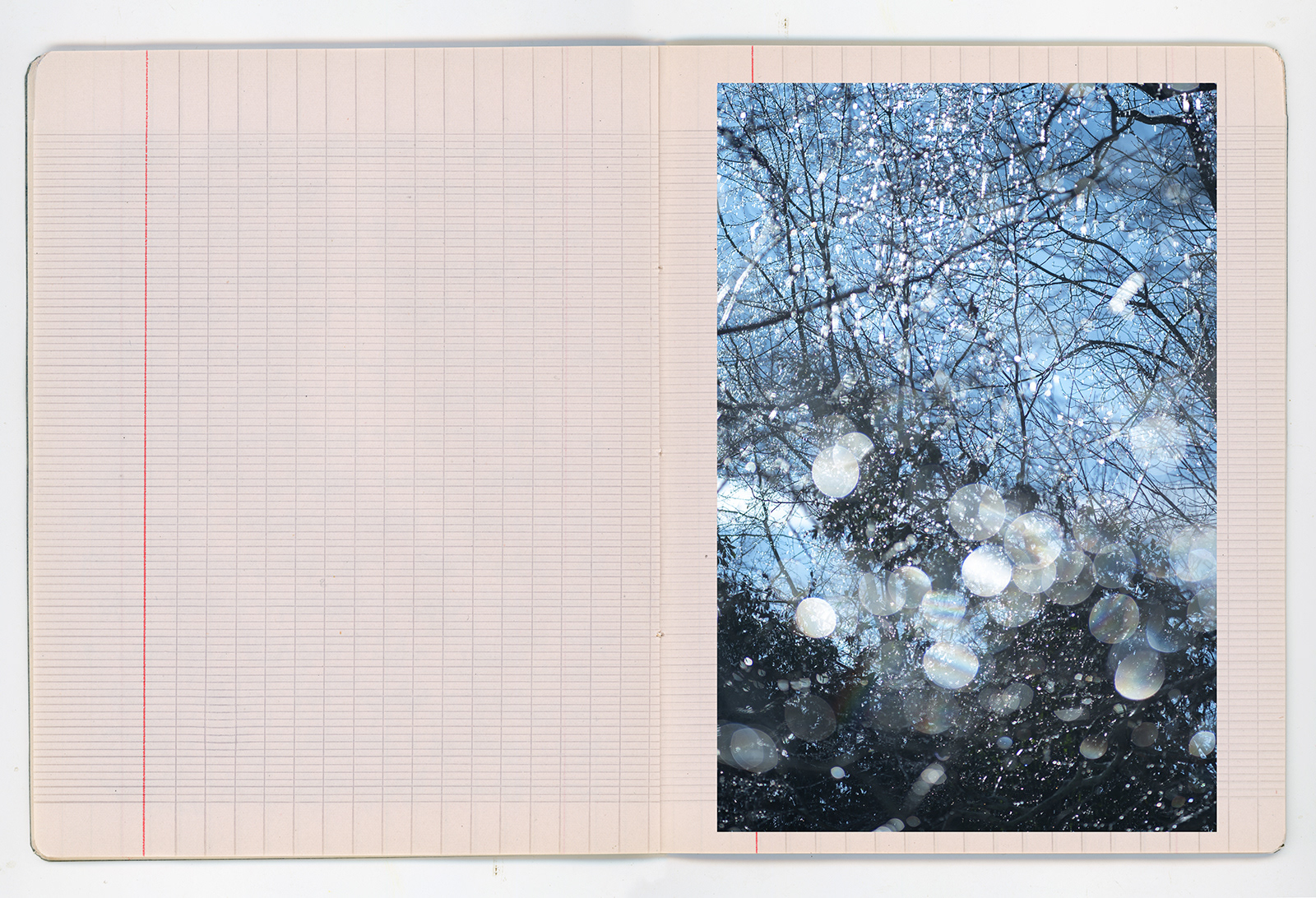

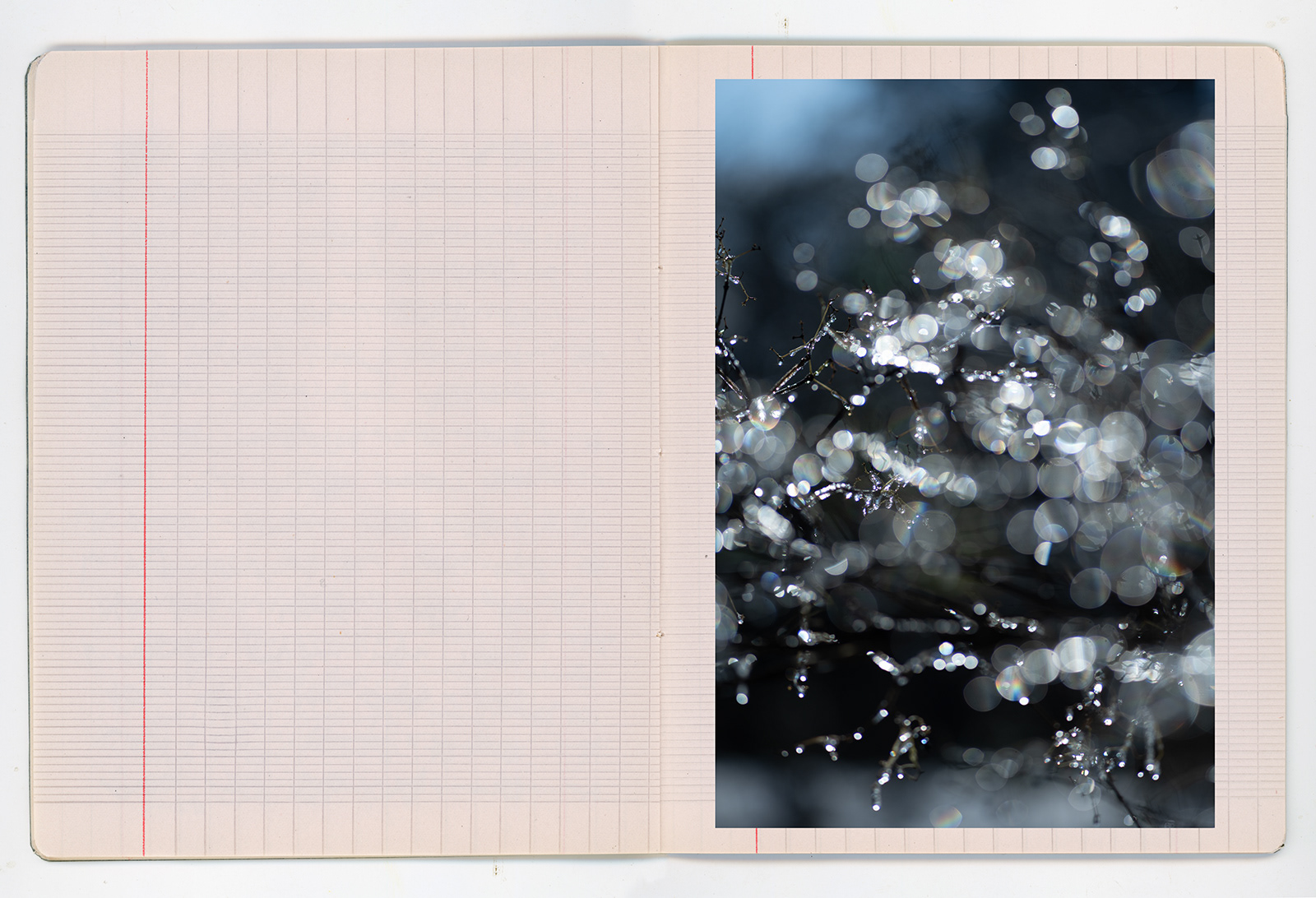

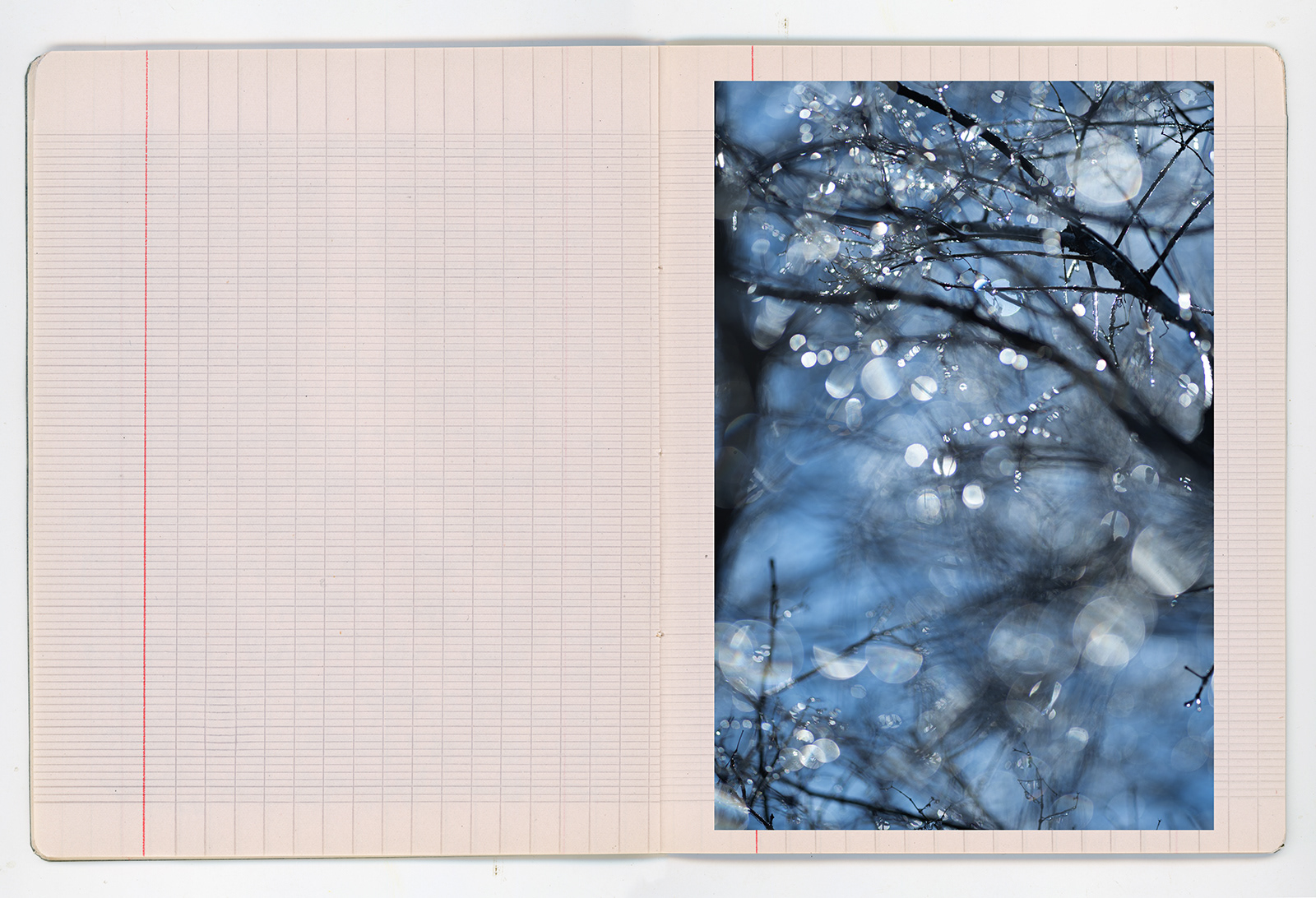

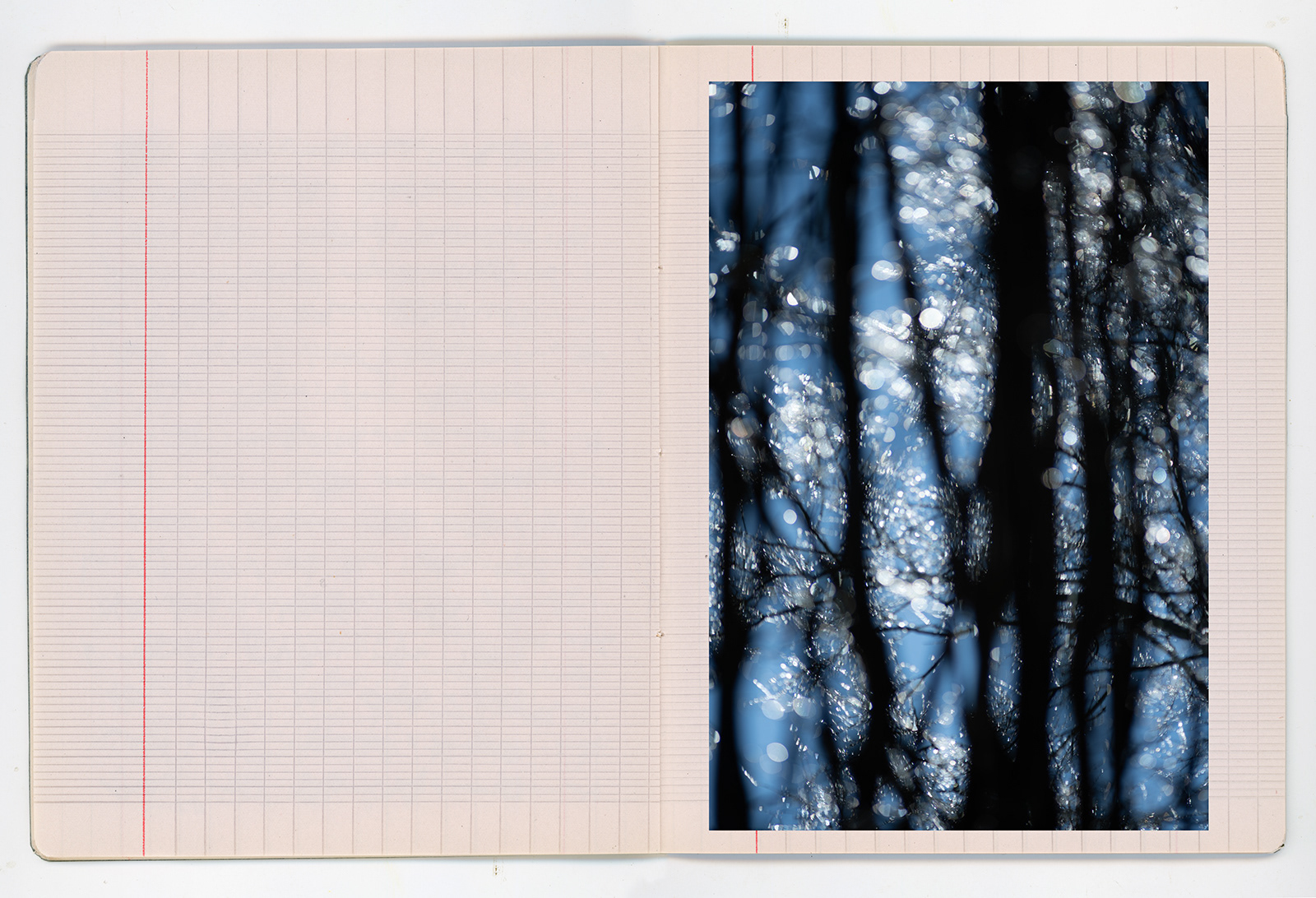

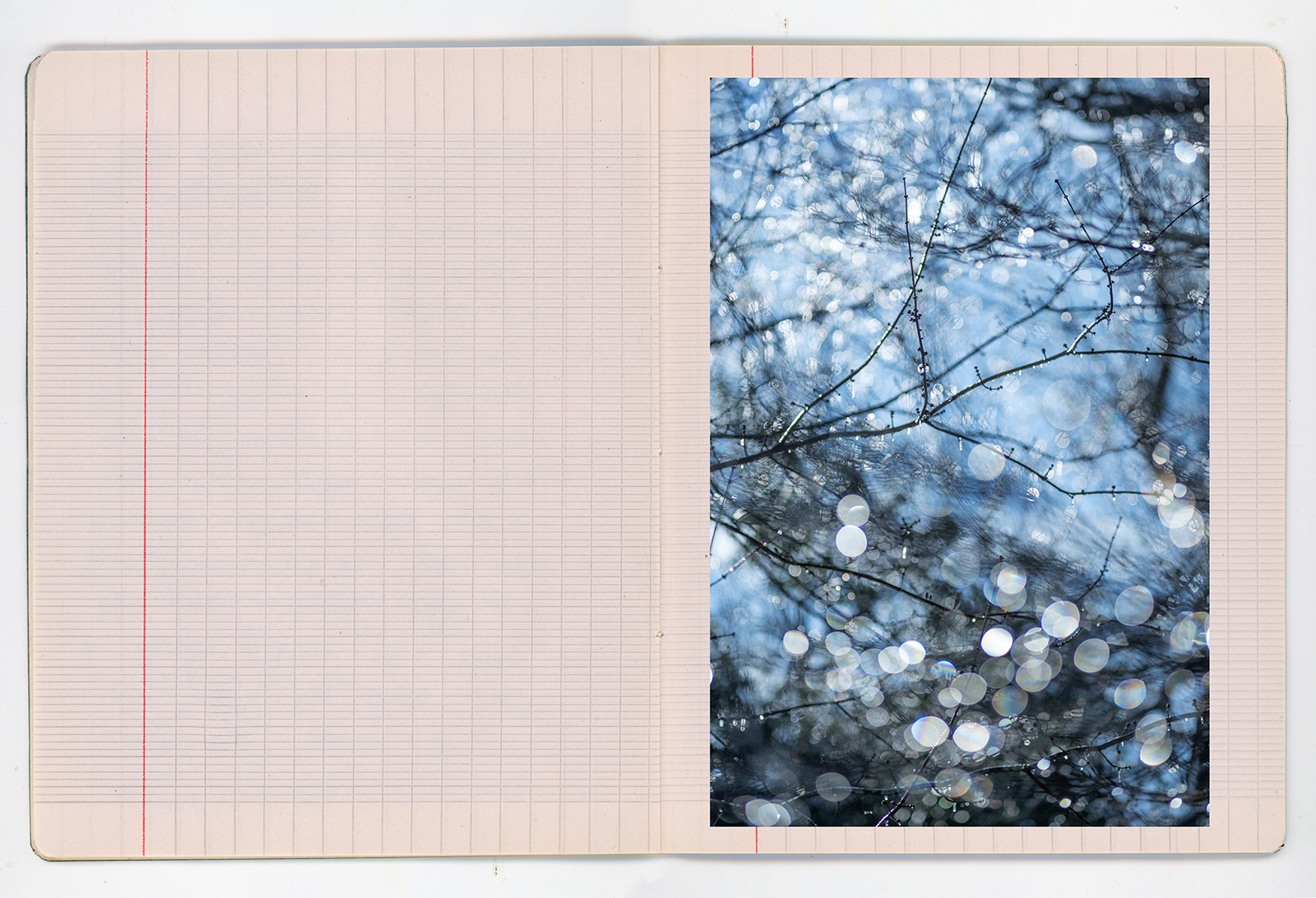

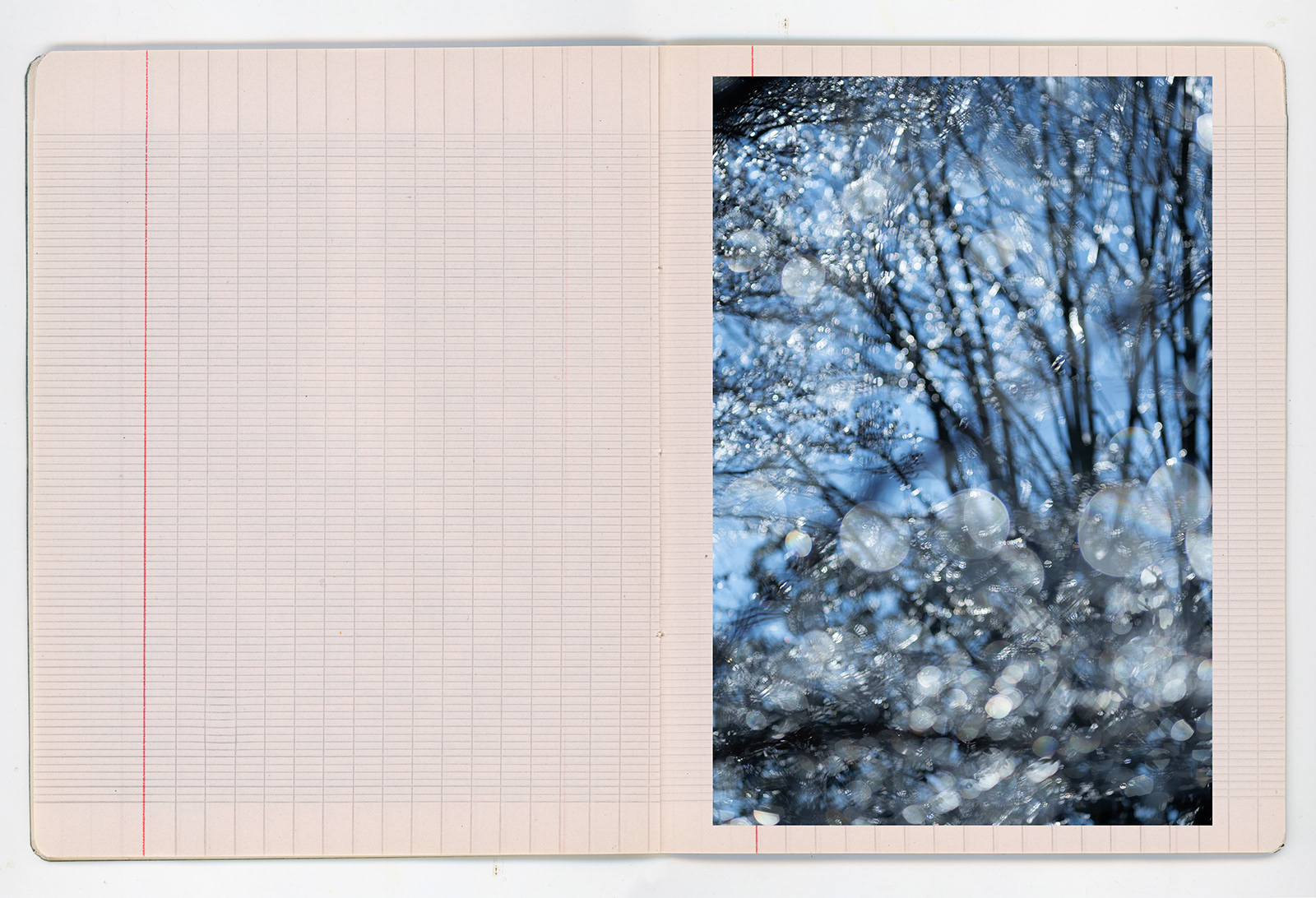

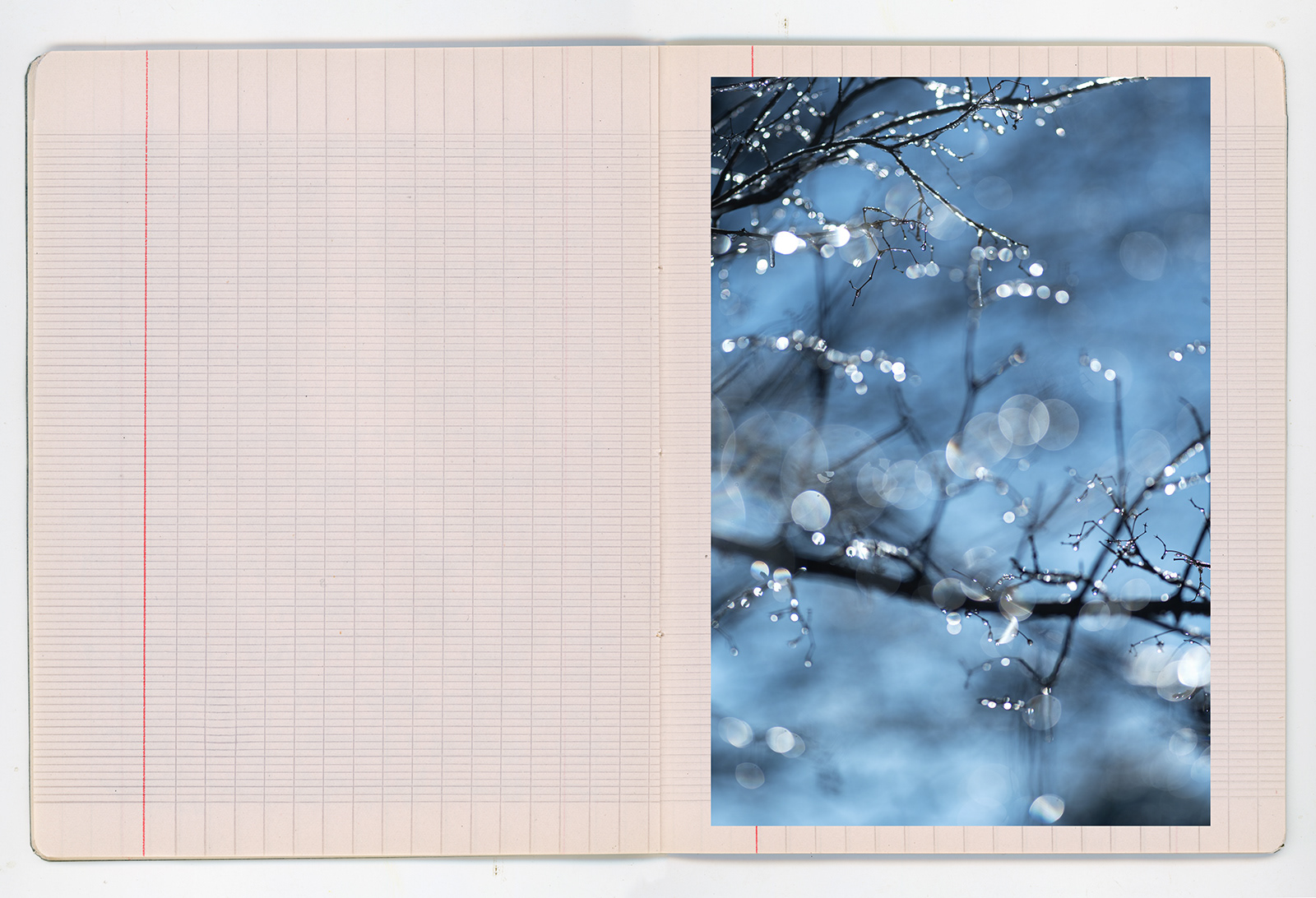

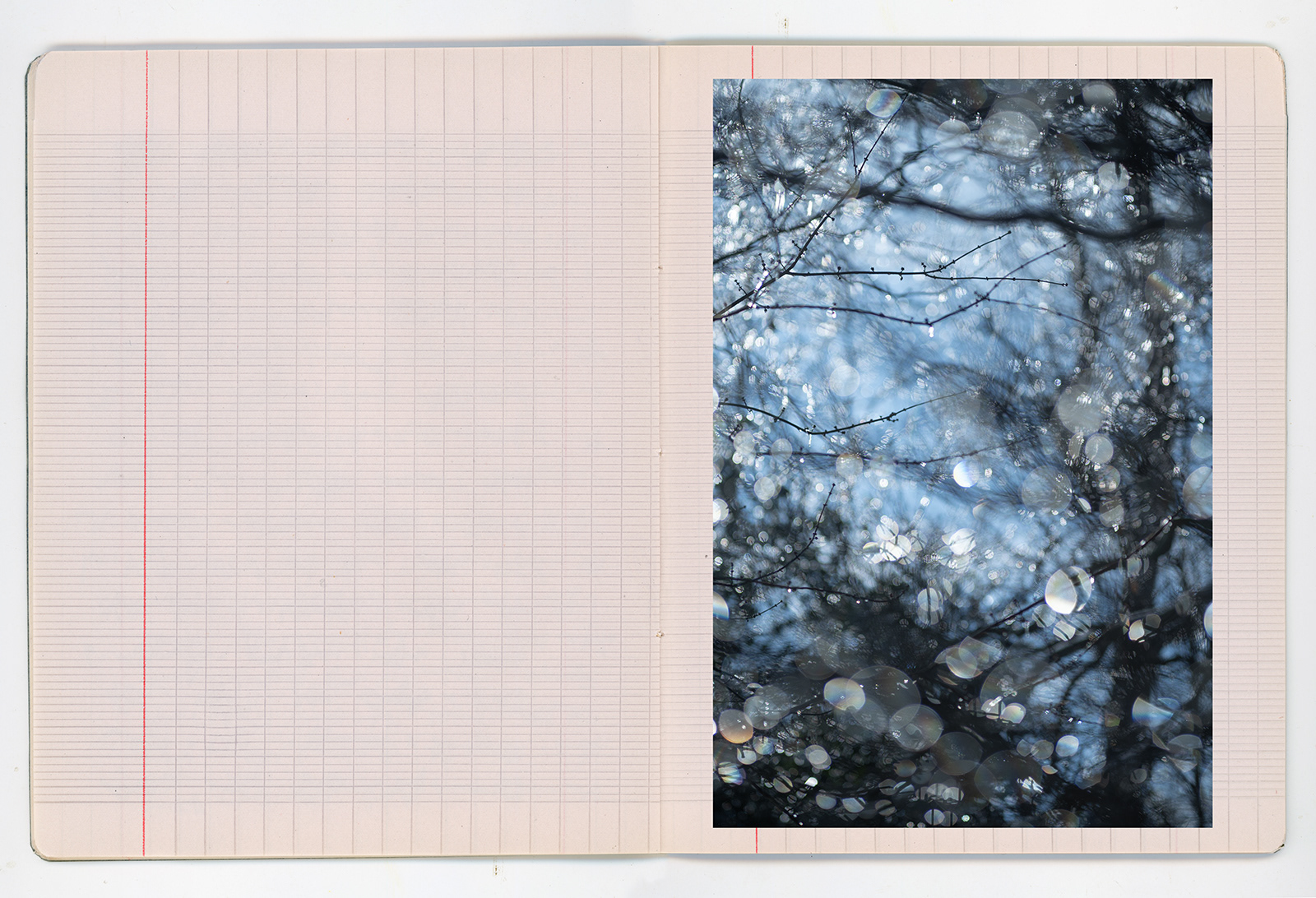

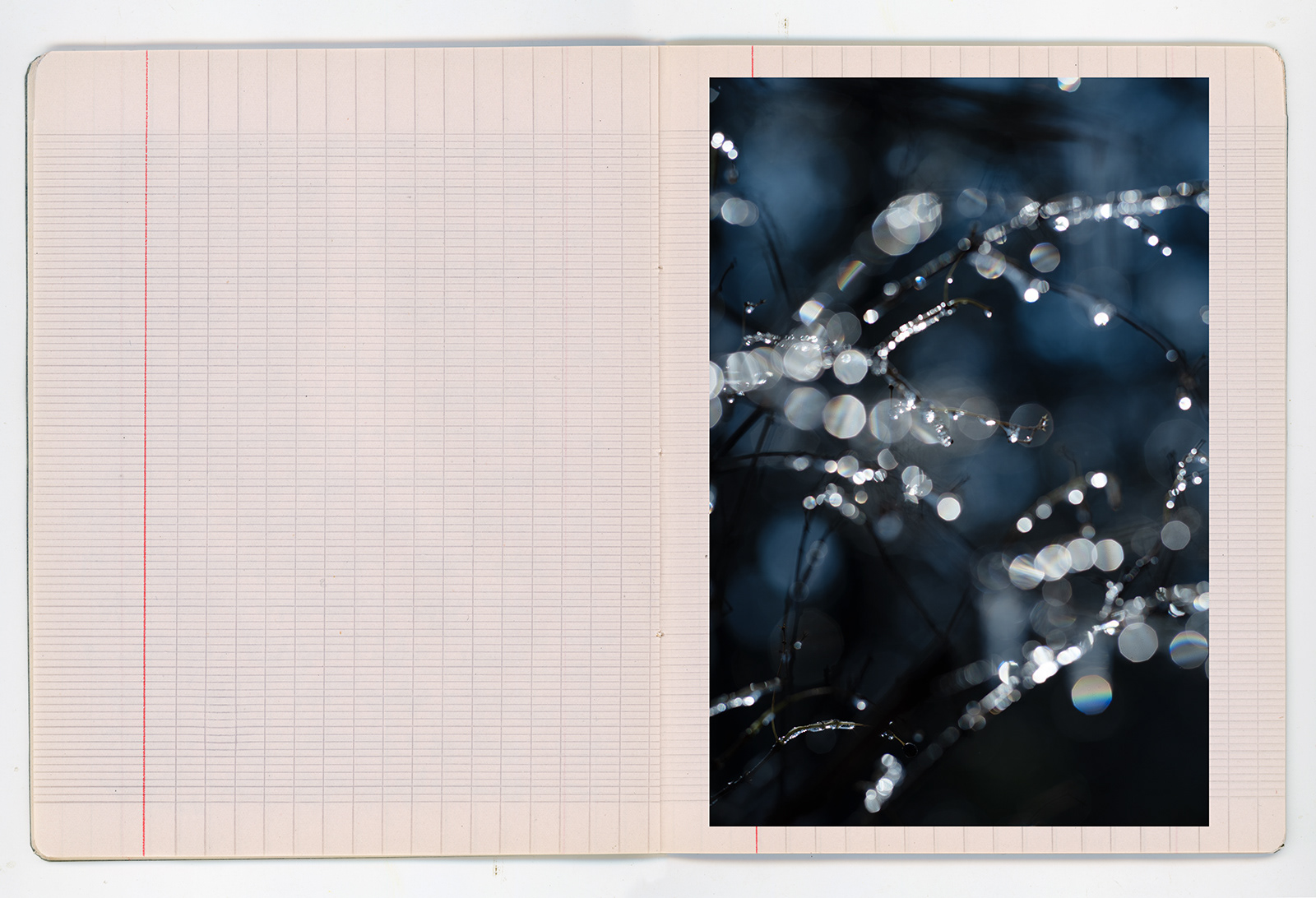

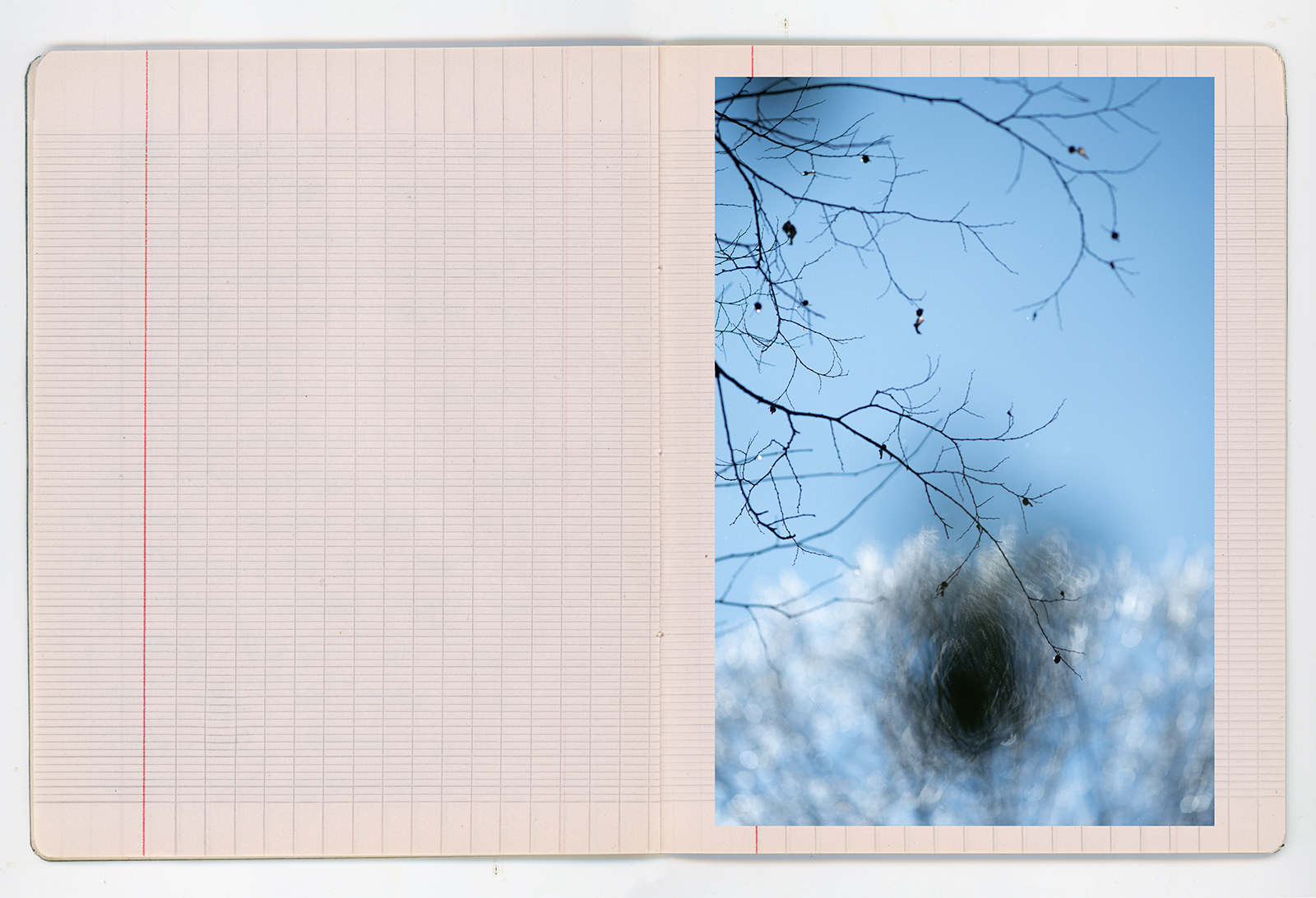

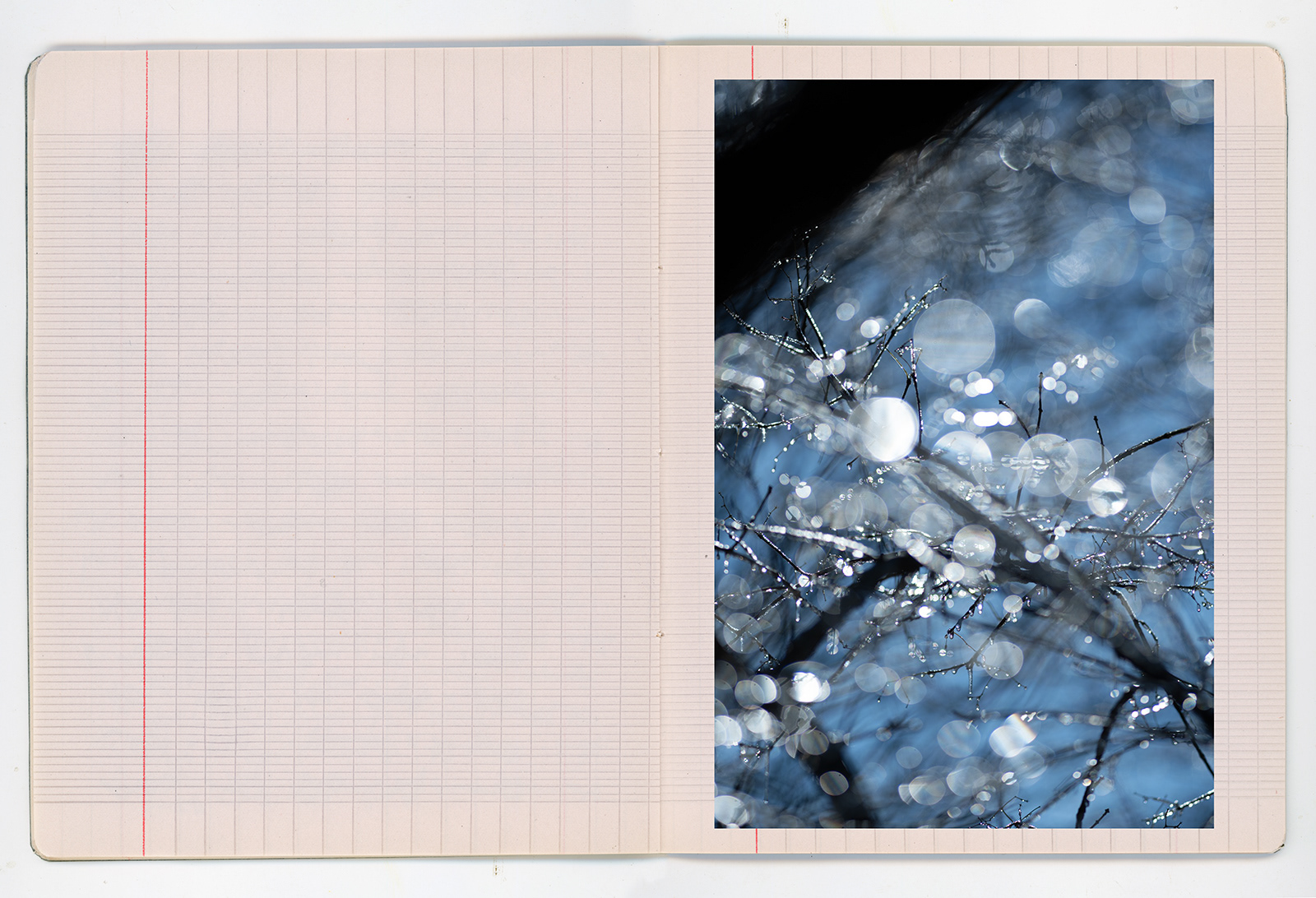

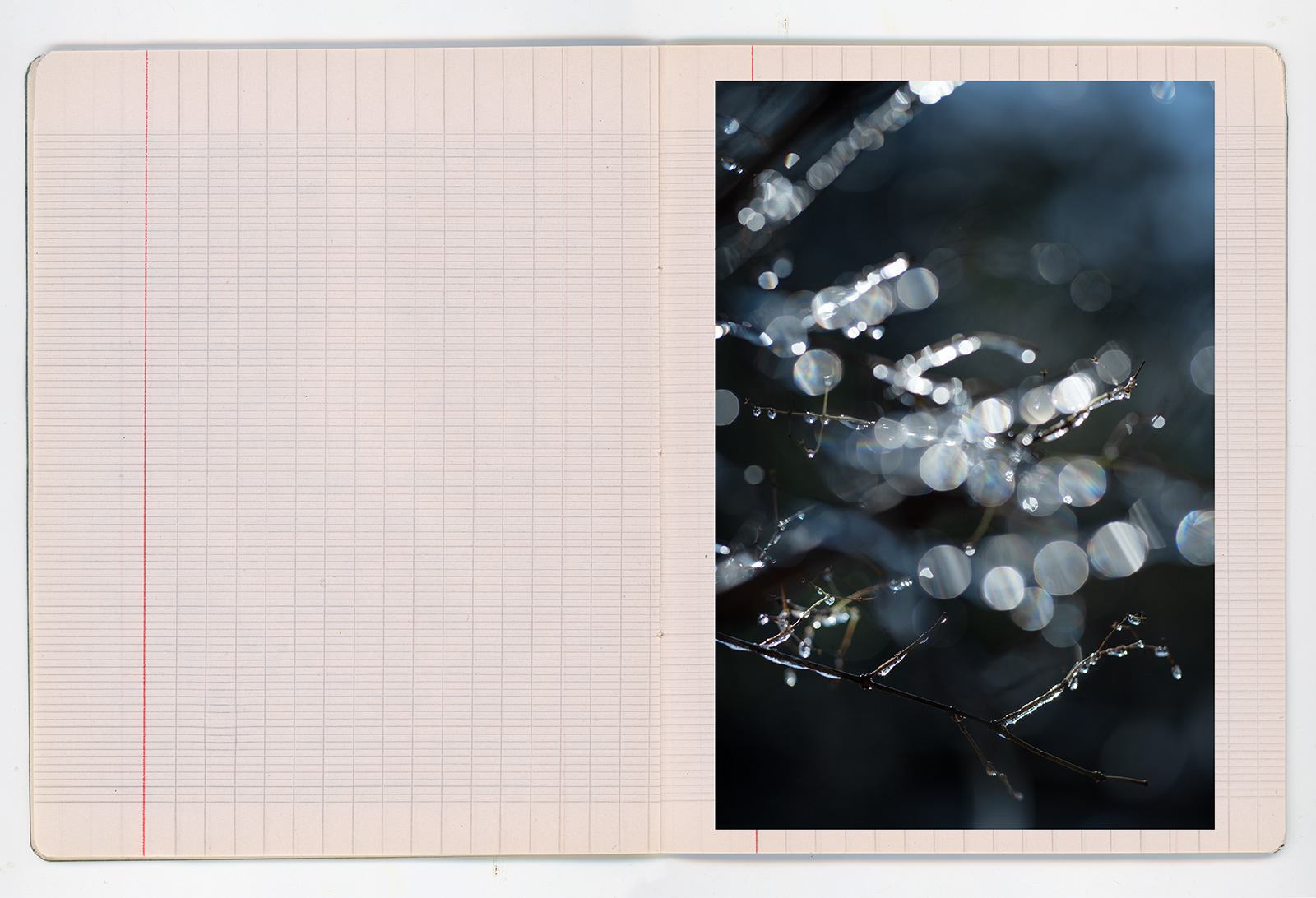

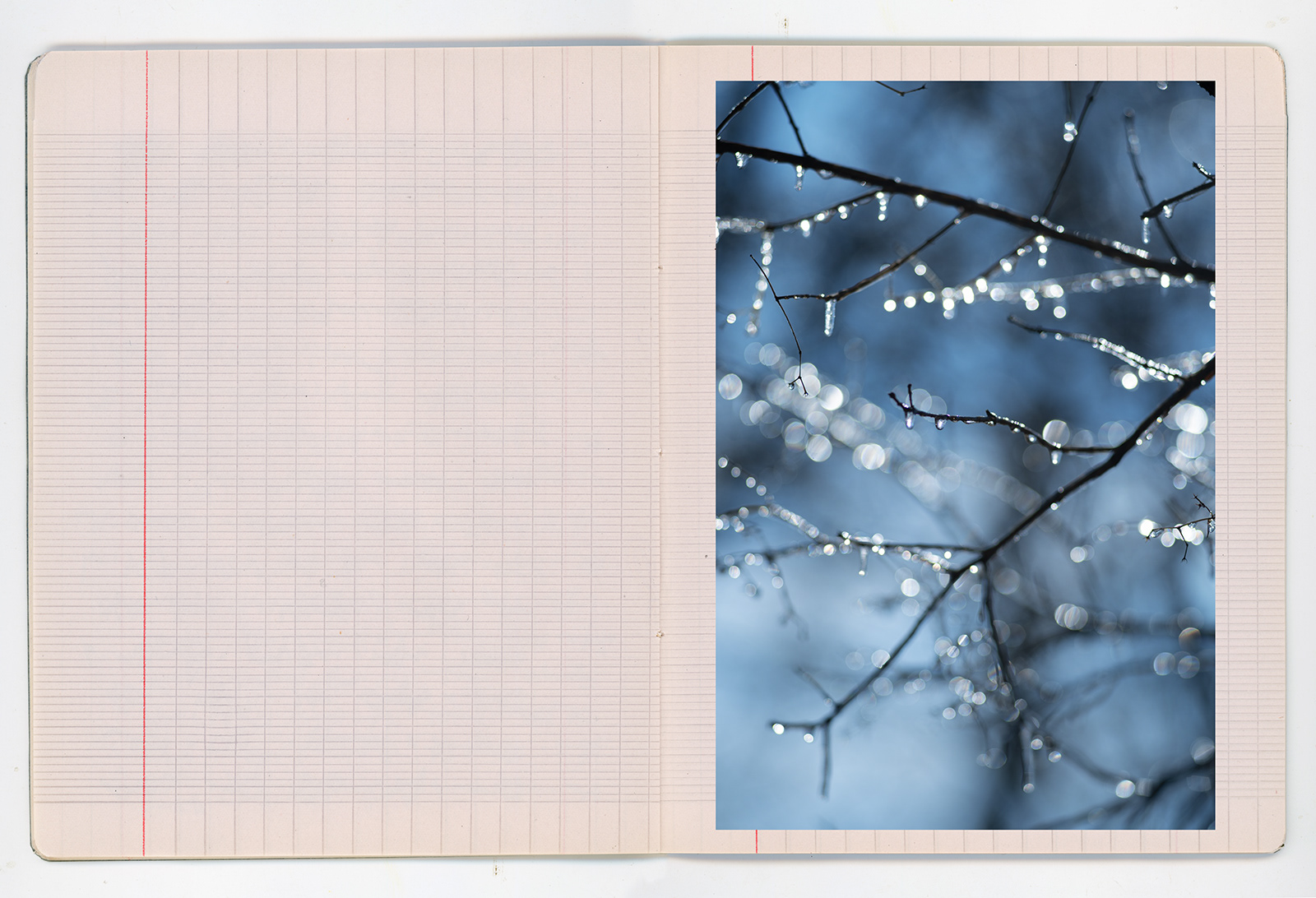

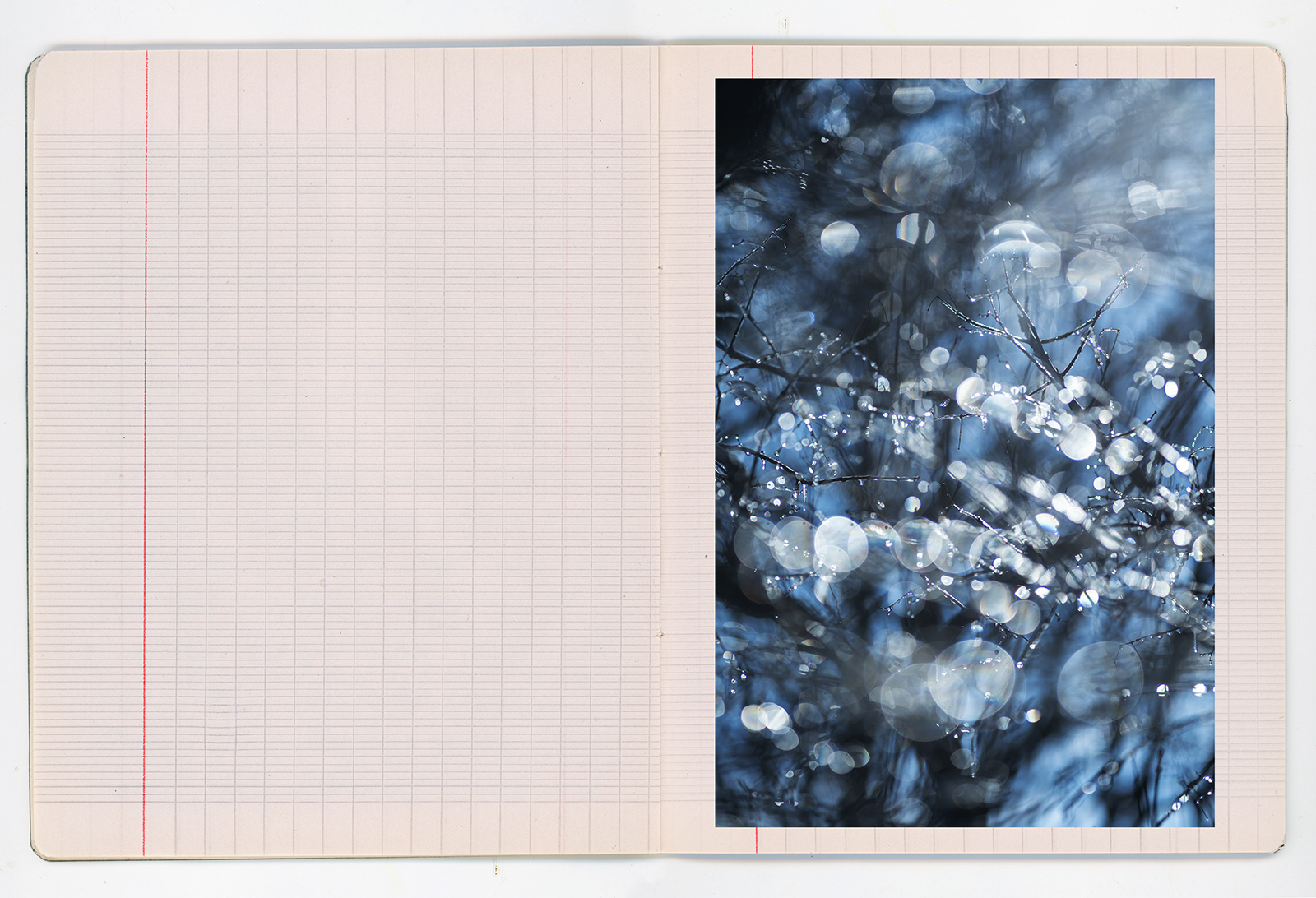

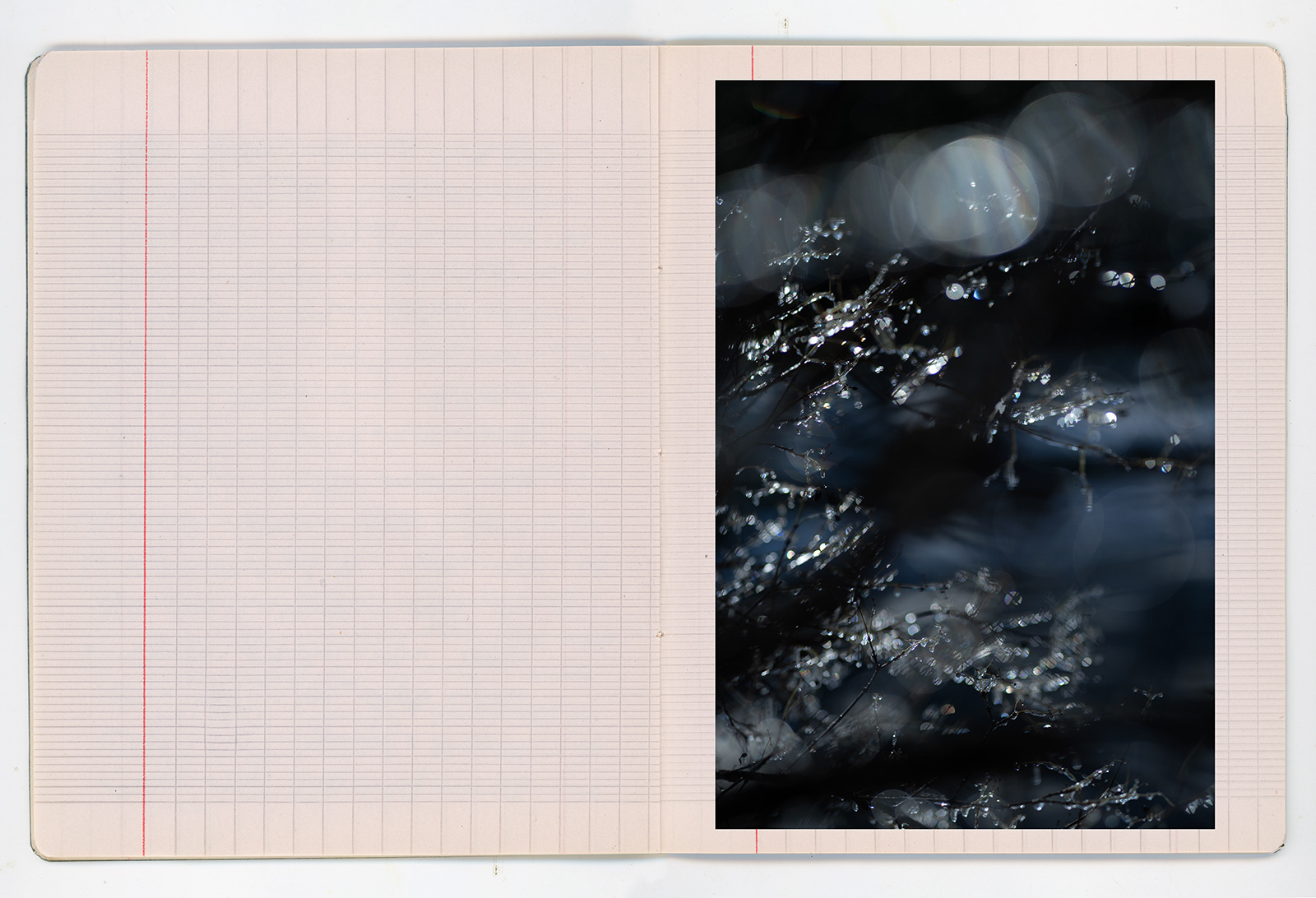

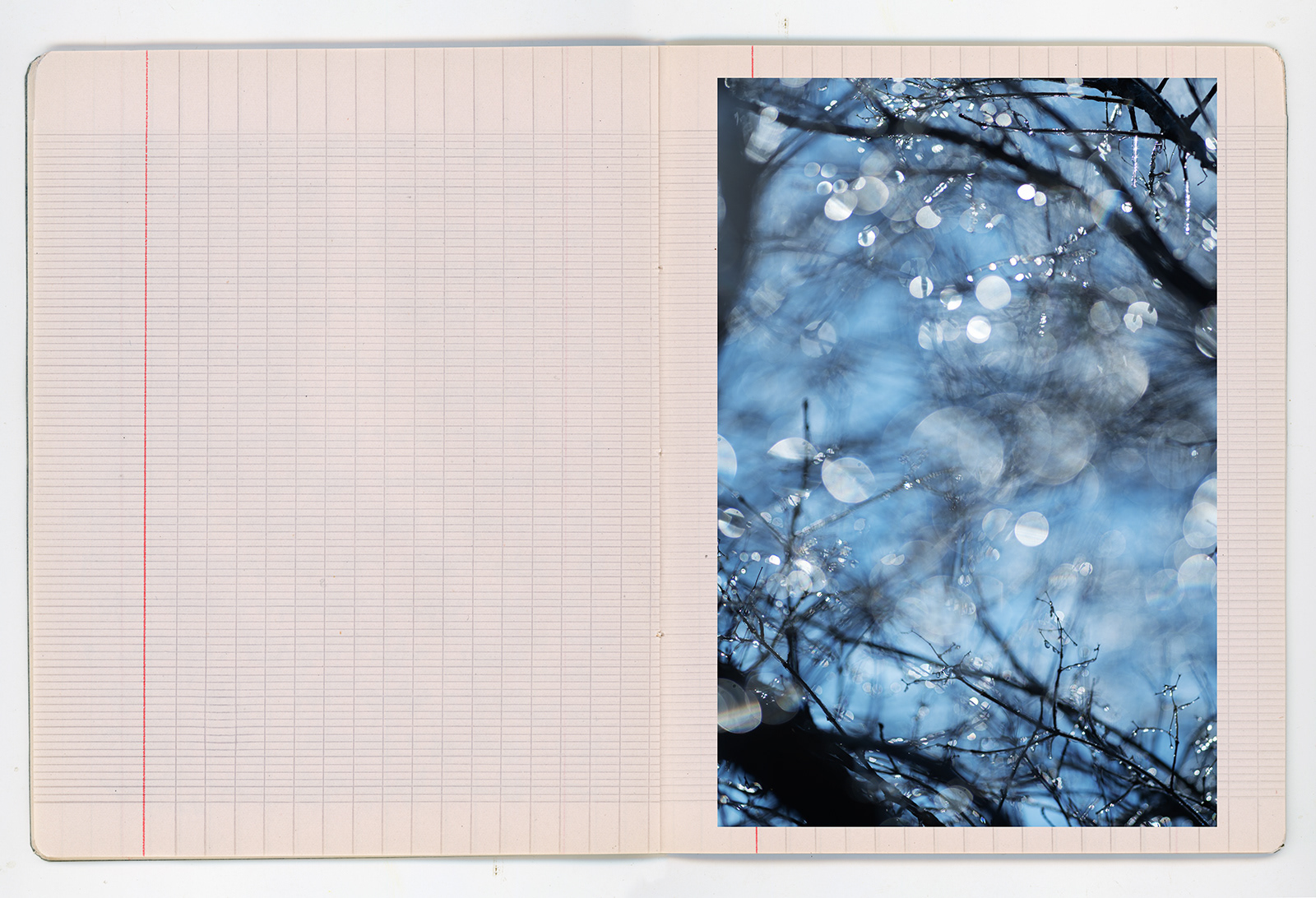

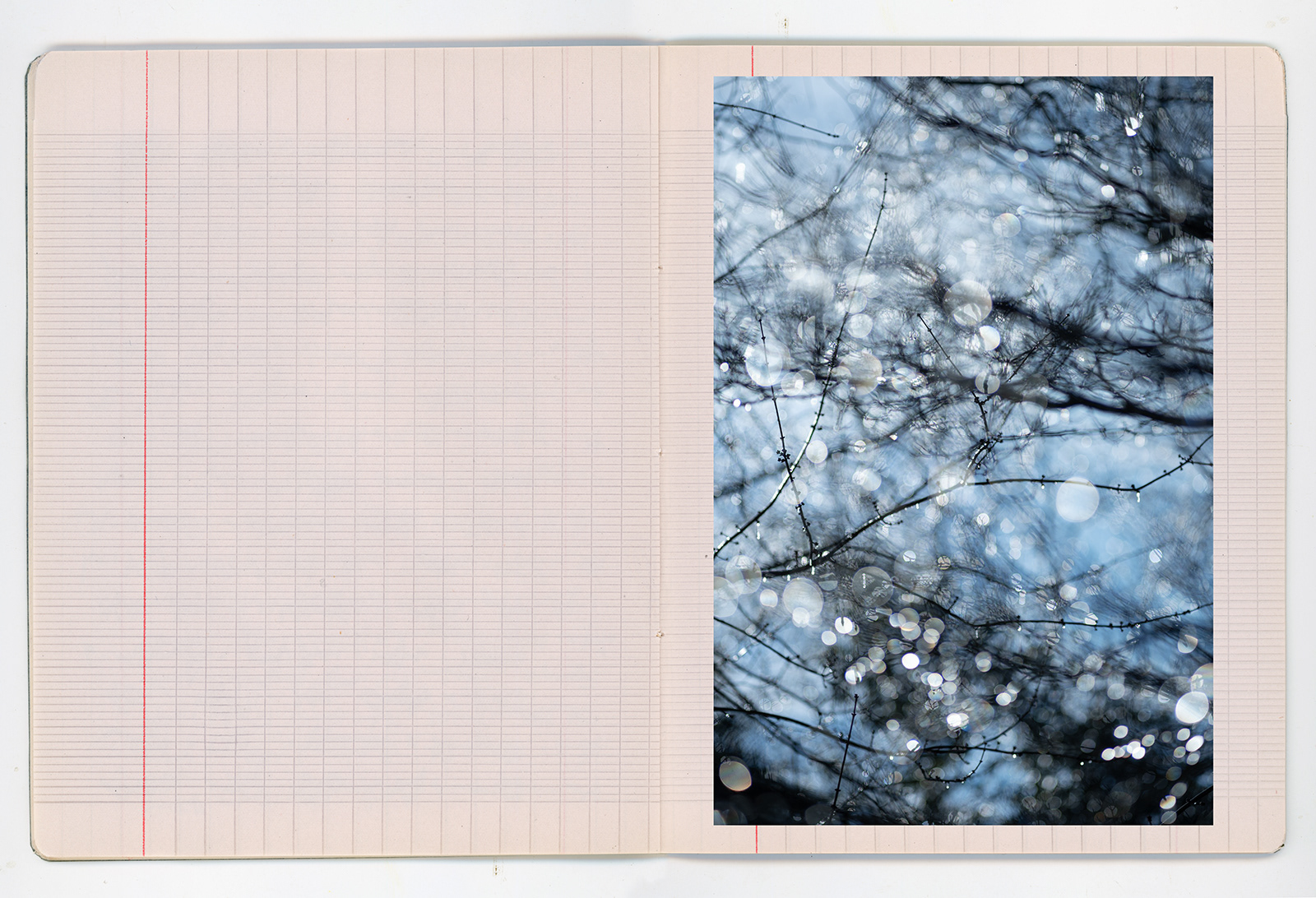

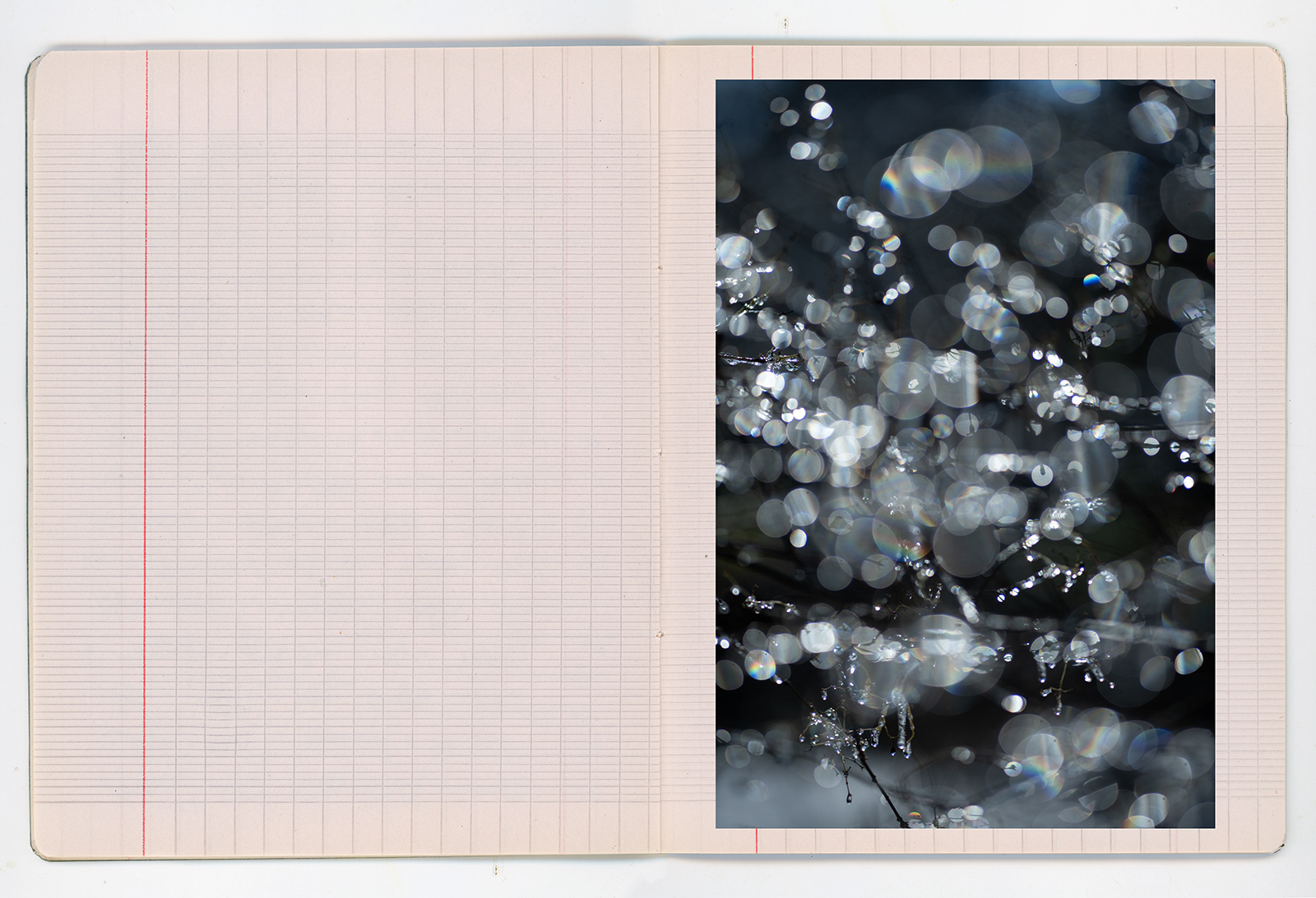

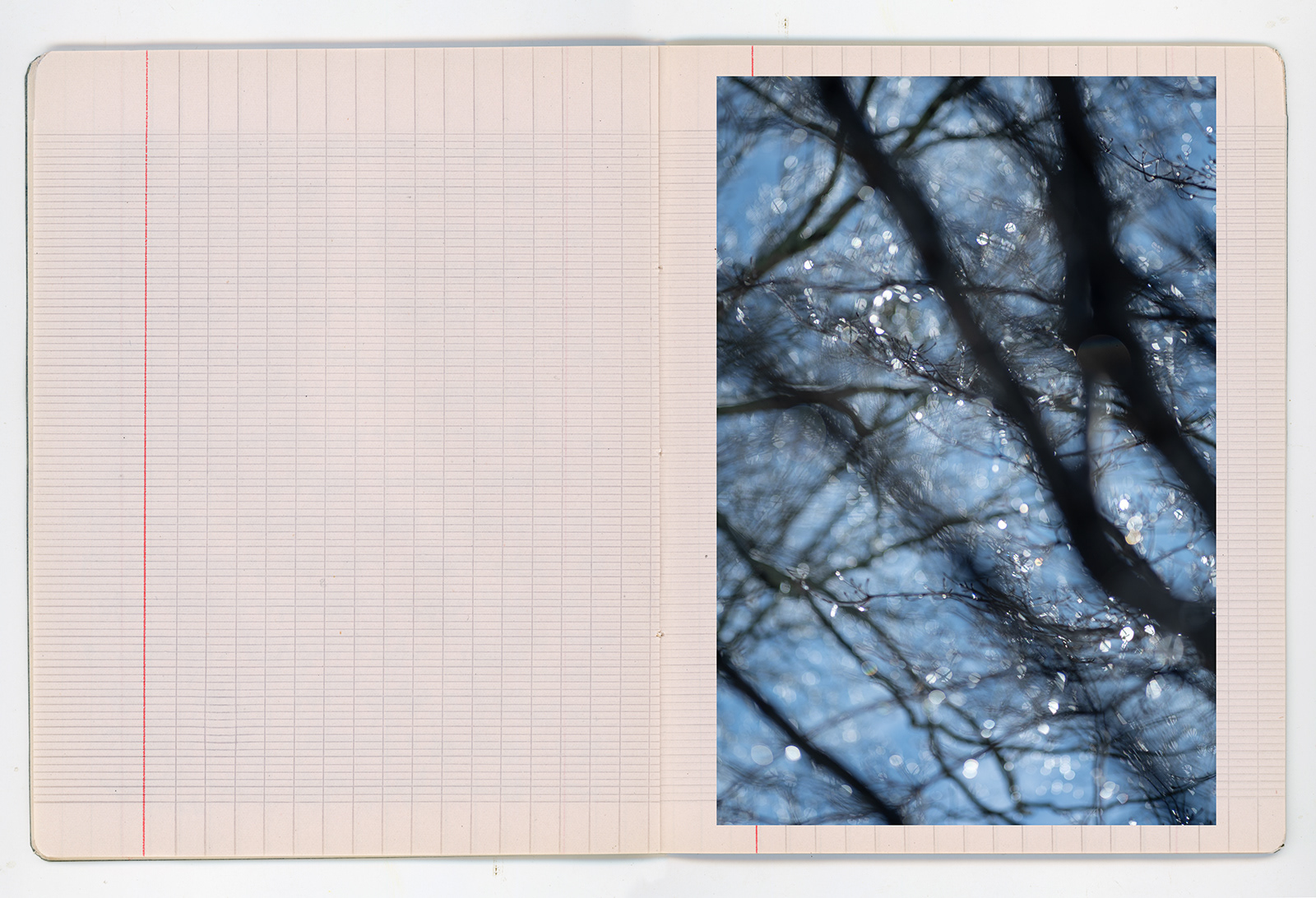

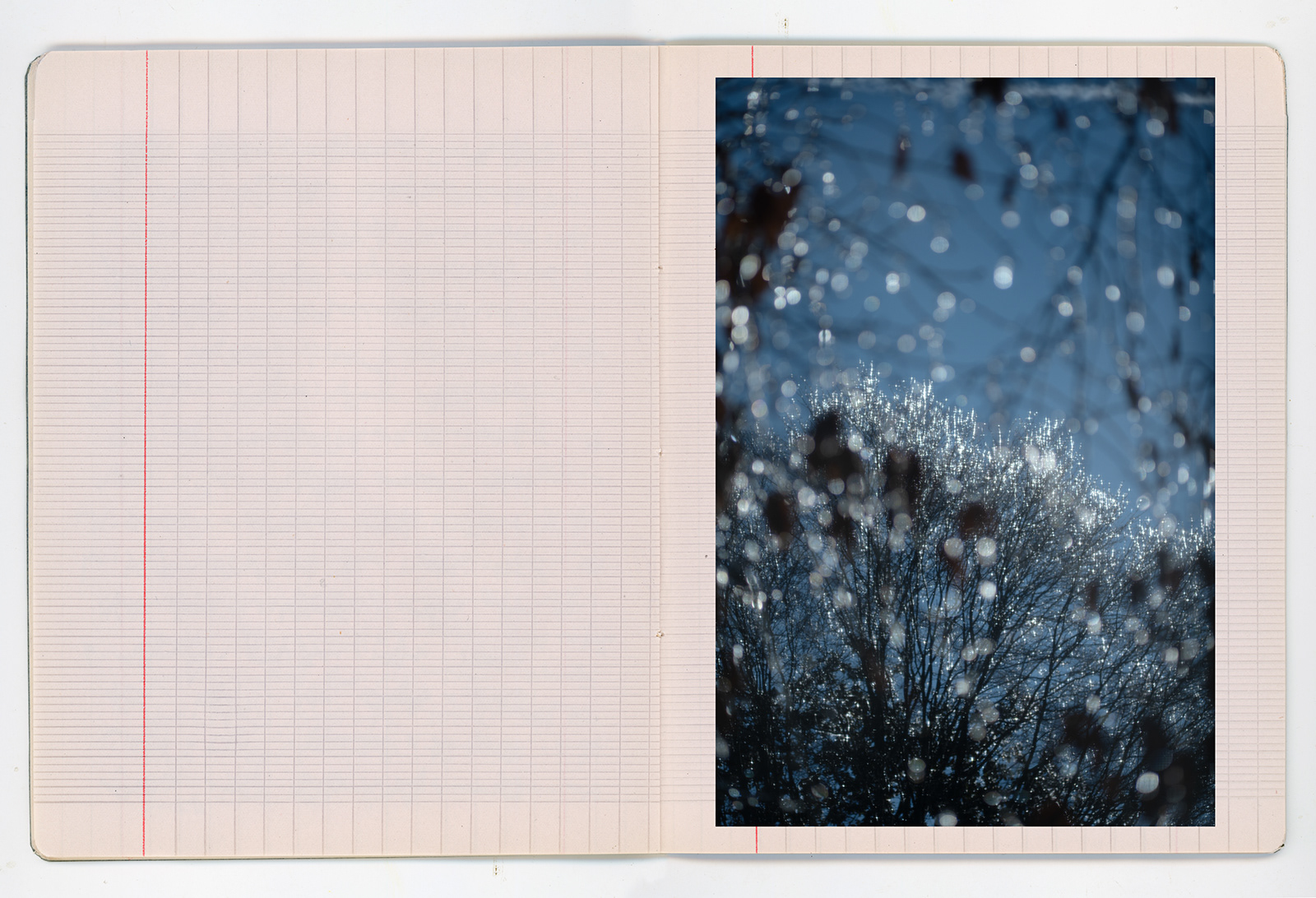

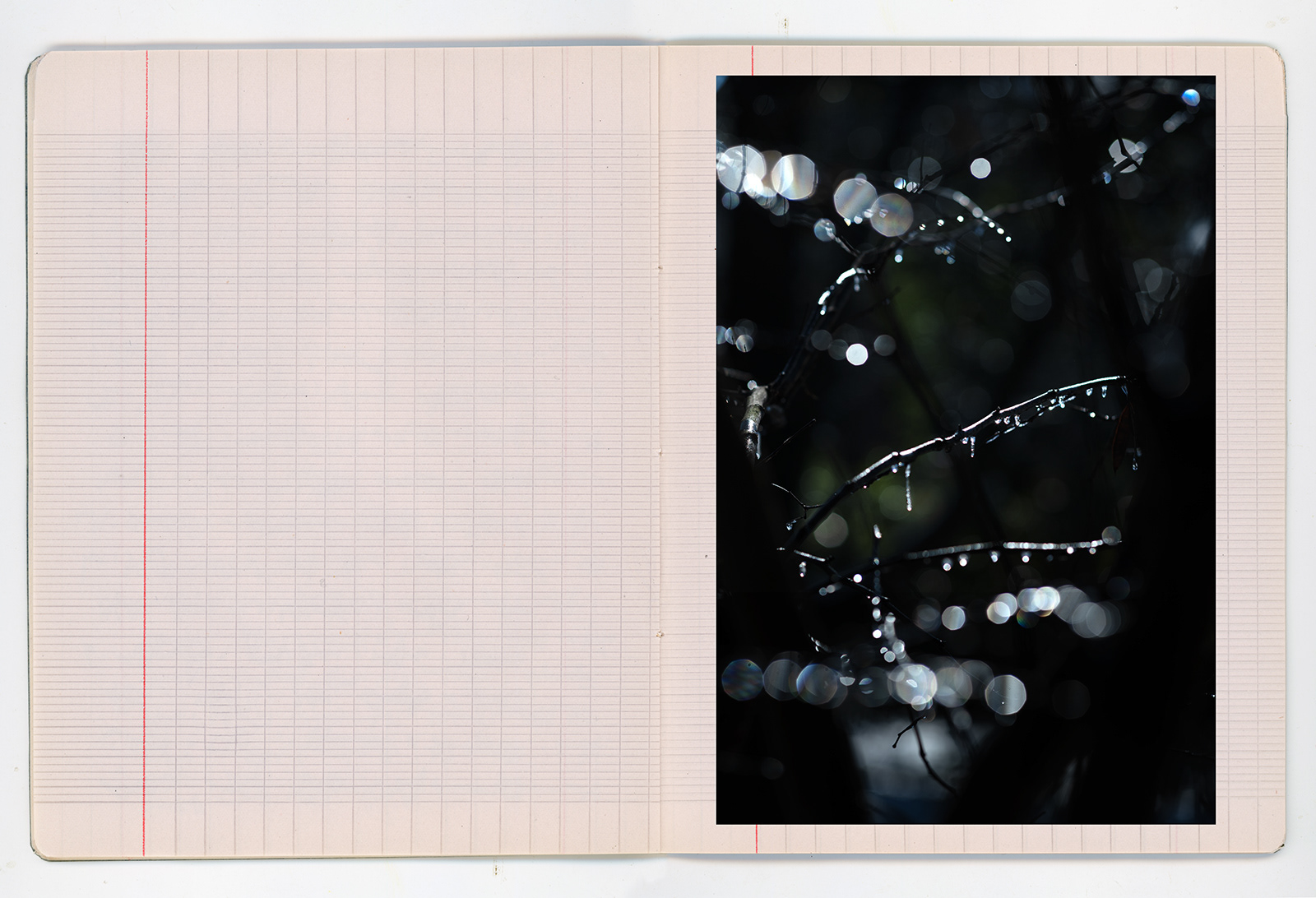

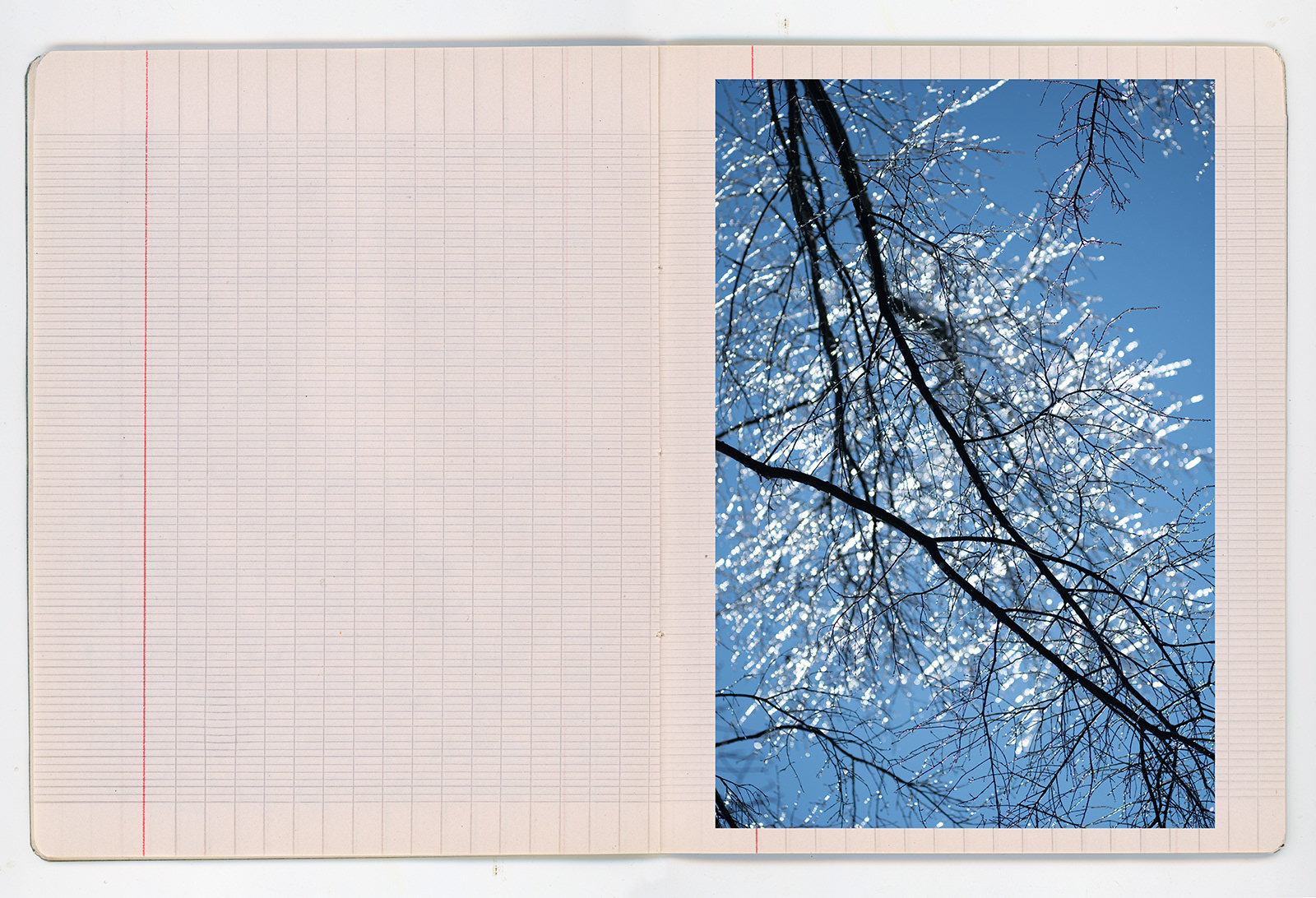

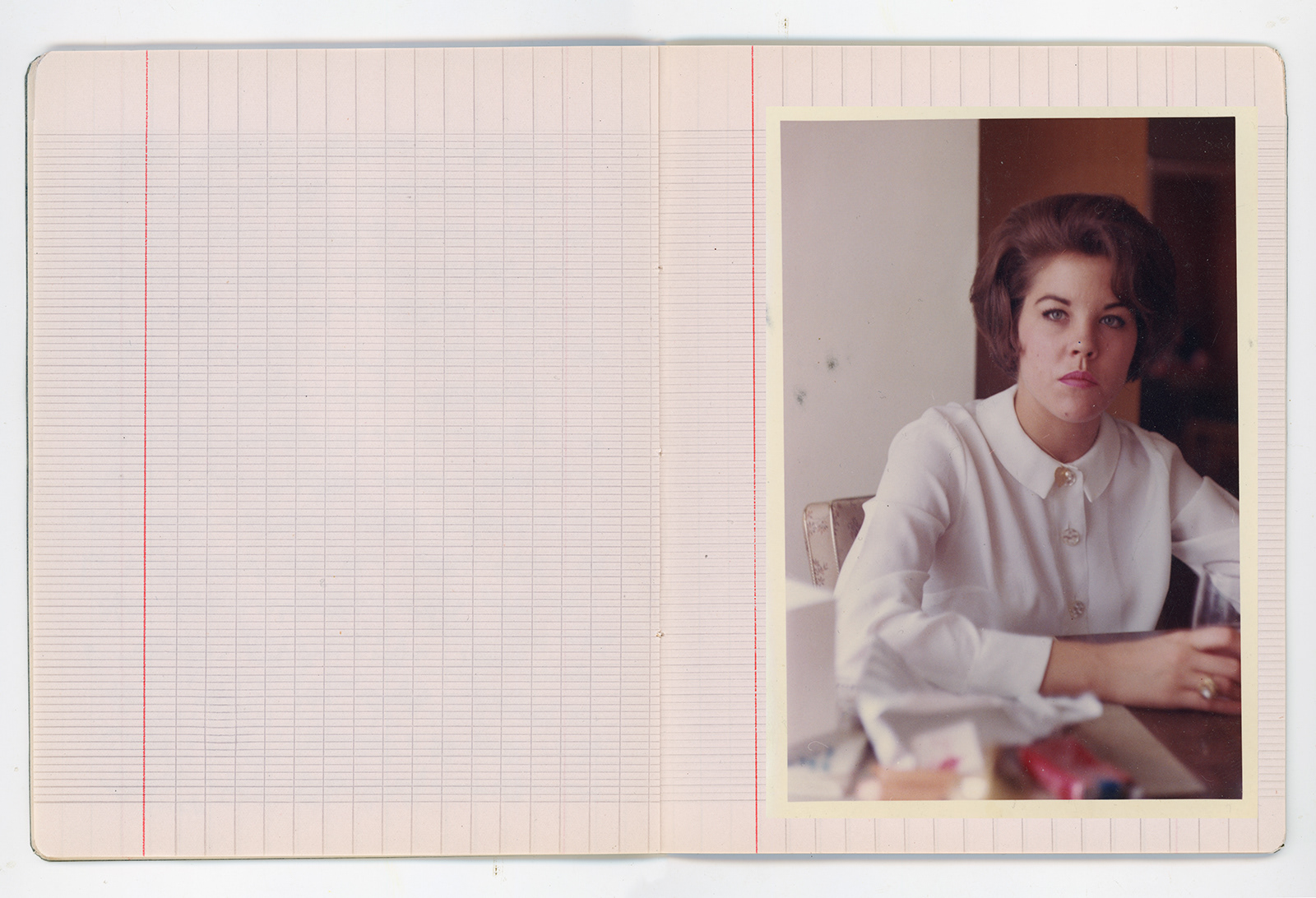

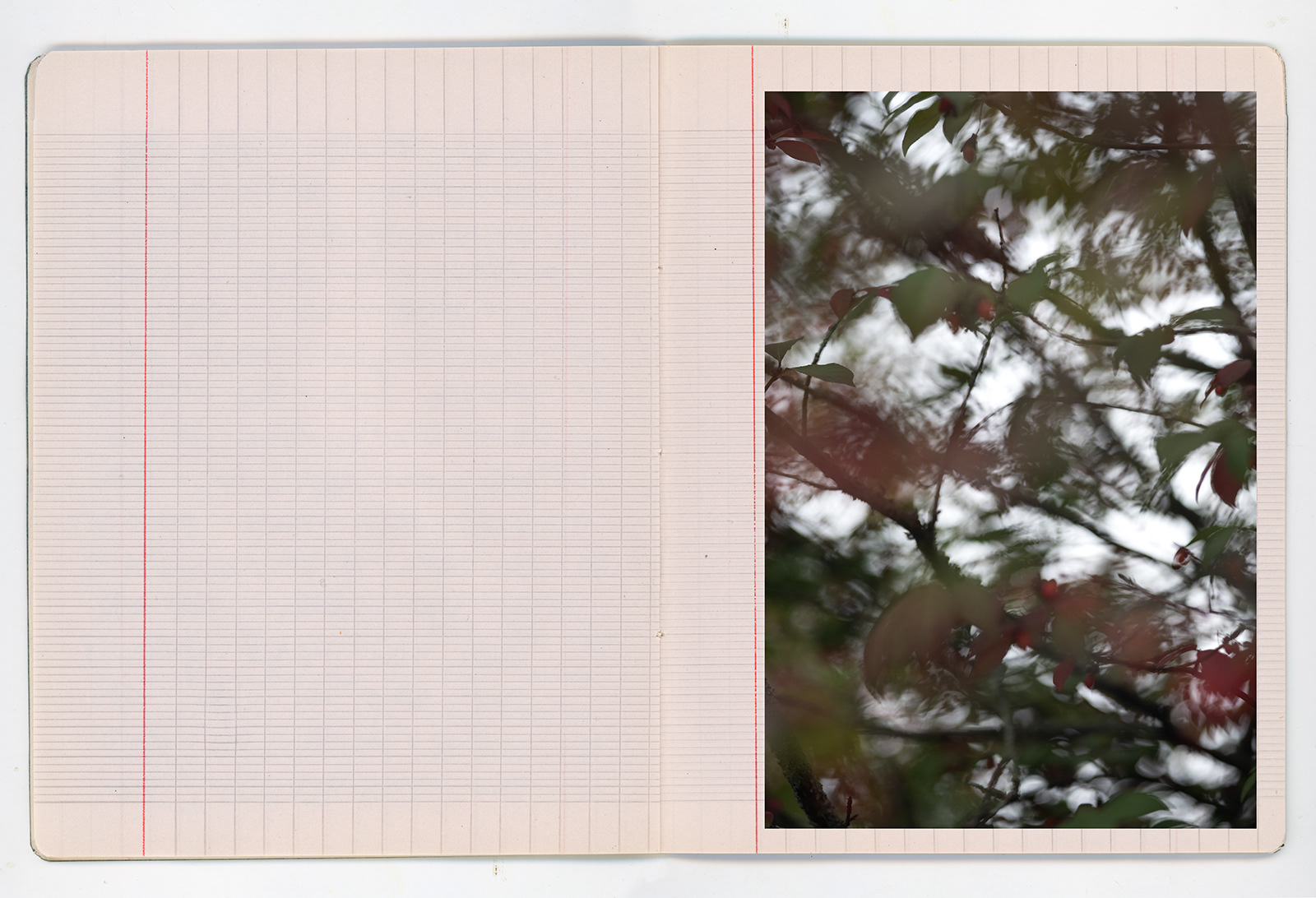

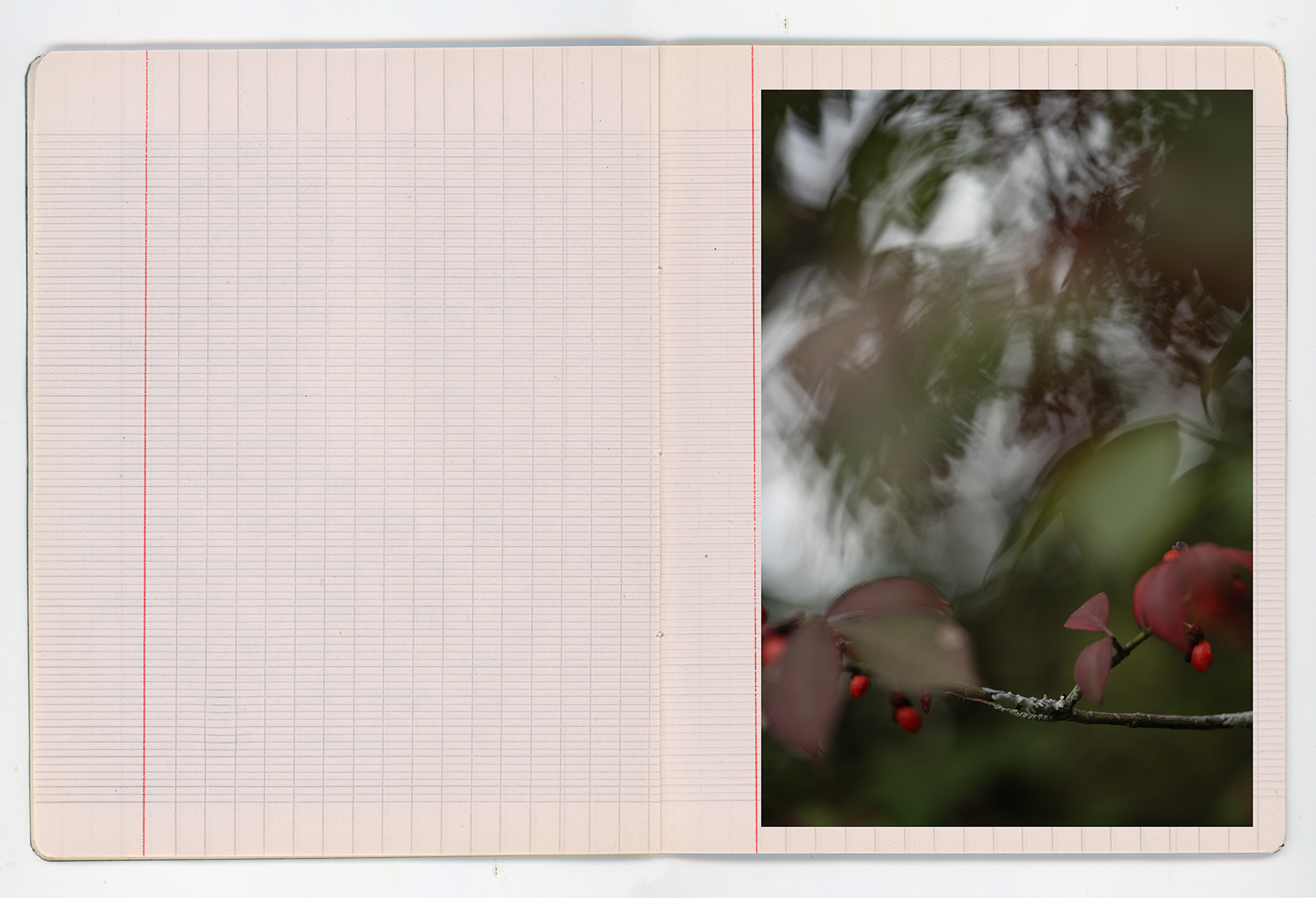

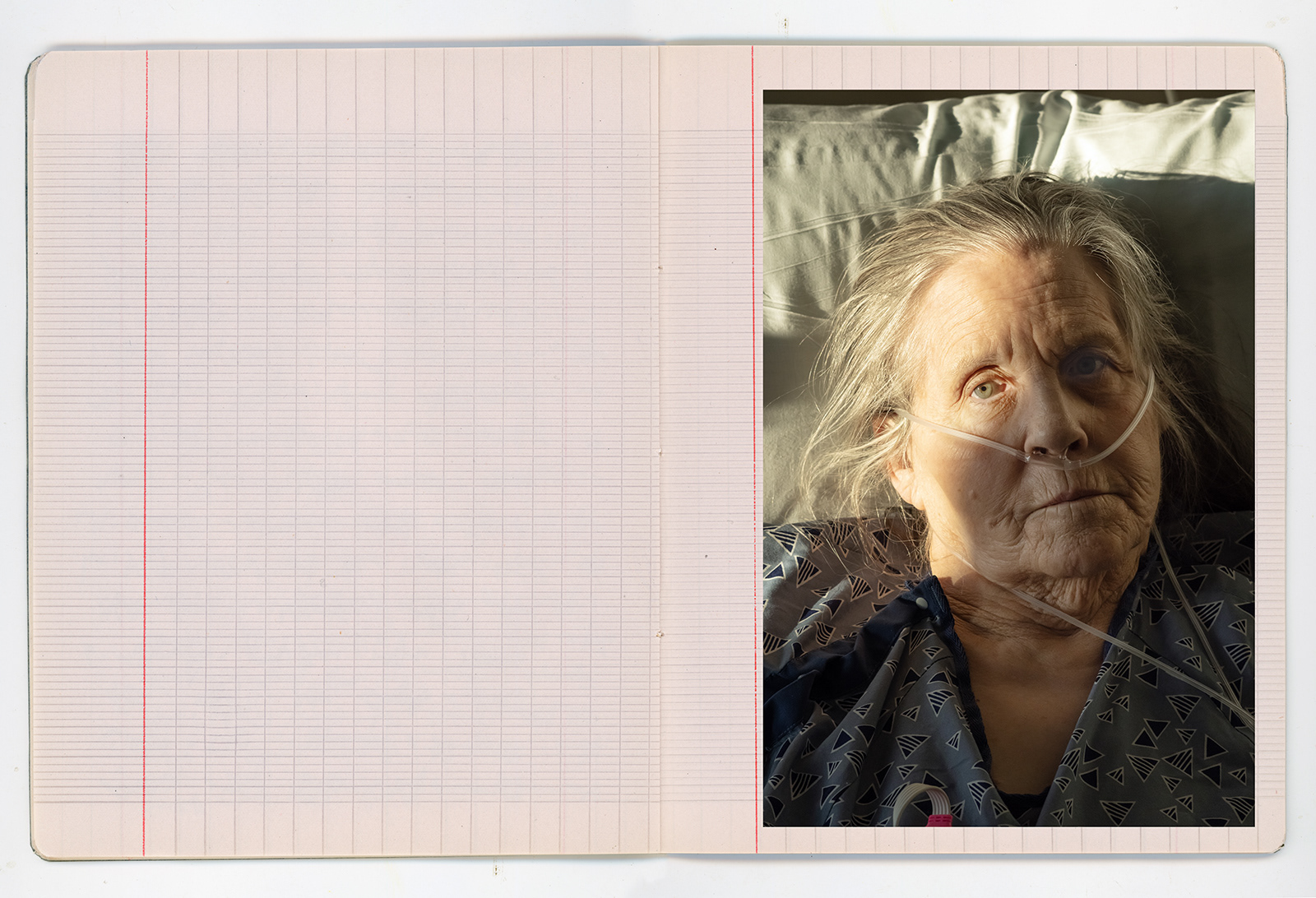

Not least, the sequence here includes photographs I made just before and just after my mother’s death—experimental observational photographs in warm autumn and in freezing winter, at night and in daylight. Two portraits of my mother bookend this book’s closing movement. The first was made in 1964, a day after her twenty-first birthday, or so she noted on the back of the picture. I discovered this picture for the first time after her death, but the gaze it holds I have always known—still, sedulous, serious about answers. The second portrait I made not long before she died, just before she began to lose consciousness, but this is not why it runs over with a sense of nearness.

In her first nature, my mother was not especially interested in poetry or poetic thinking. Perhaps now it is different. For me, this book's dialectic of drawings, poems, and images—plus of course the silence within which convergence and divergence stand to happen—is among the things for which I feel honestly grateful in this moment.

Atlanta, February 2025