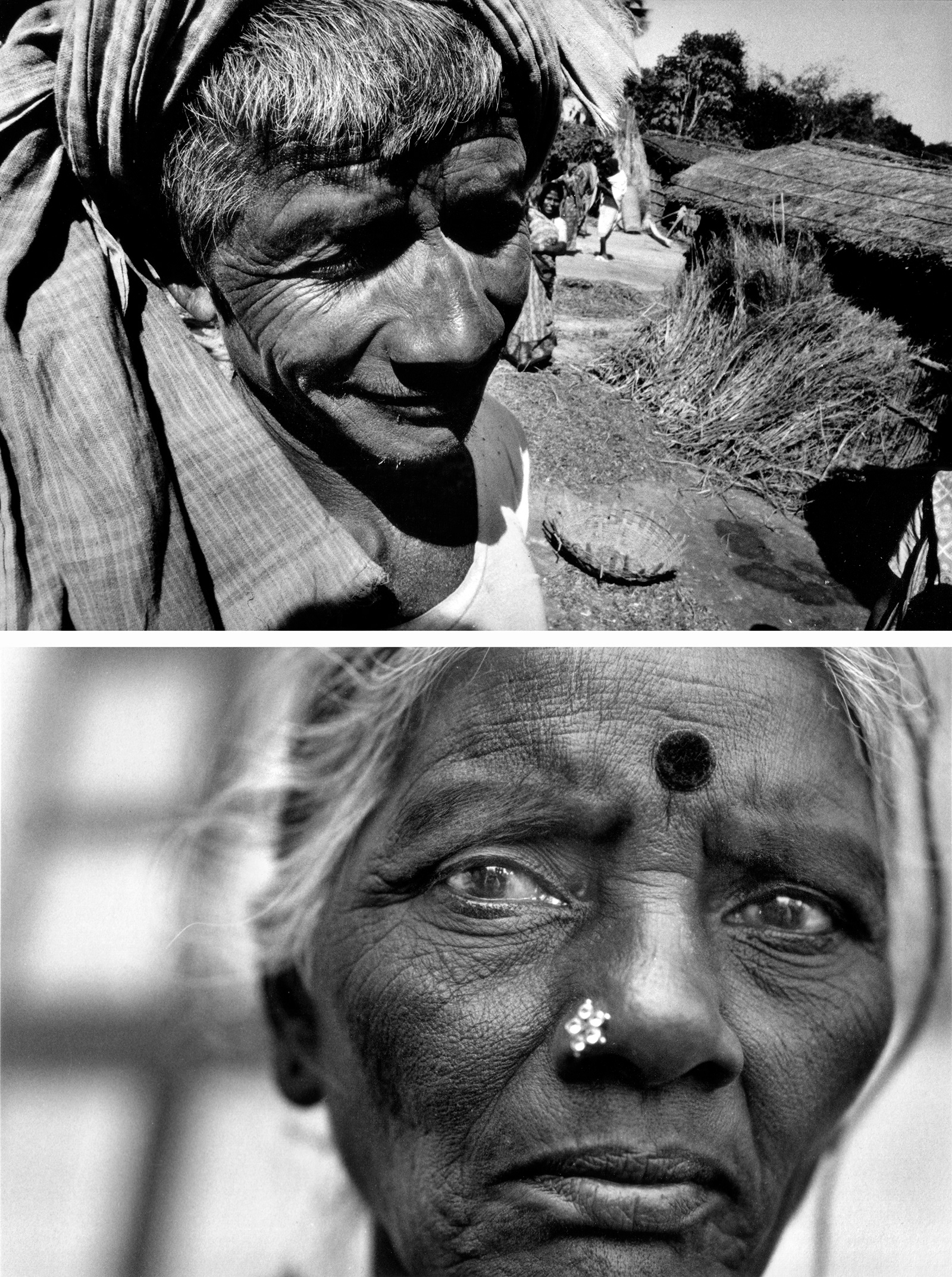

The Villages: Rural India at the End of the Twentieth Century (1990-1997) is an immersive investigation of rural life in the Telugu speaking regions of southeastern India. In the manner of an open and critically minded encounter, the project explores the social and economic conflicts of a traditional hierarchical society on the periphery of the globalizing world.

From the Introduction:

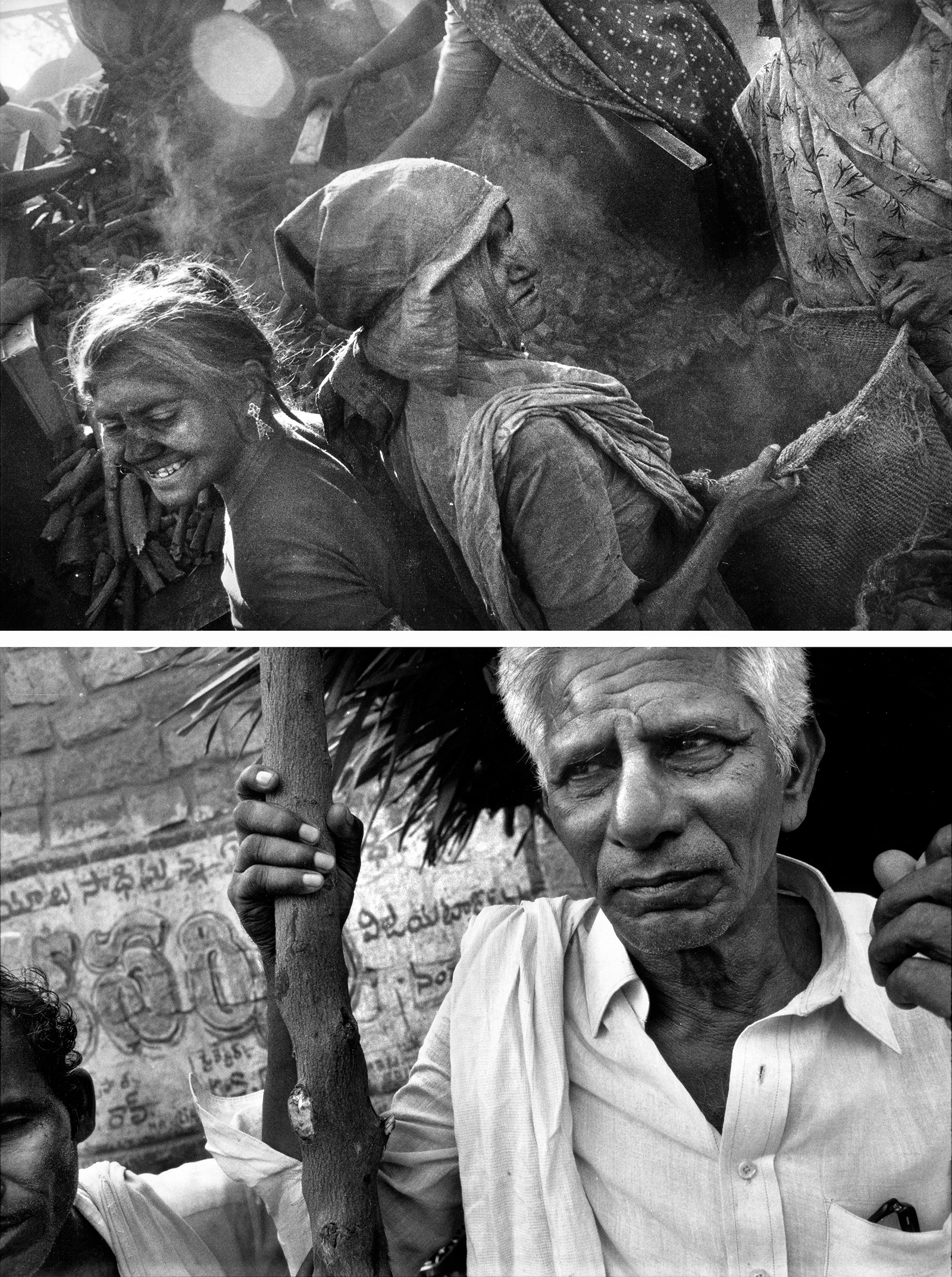

In the global discrepancies between wealth and poverty—or, to use other denominators, development and underdevelopment, Northern and Southern nations, metropole and periphery—what terms adequately describe the interpenetrated quality of prosperity and vulnerability within a country such as India? India is not merely and undifferentiatedly a poor country. Rather its growth since the Cold War is what might be called discretely uneven: not an overcoming so much as an elaboration of the inherited imbalances of central planning and the quasi-socialism of command-style democracy, which themselves sit atop the imbalances of the colonial and the precolonial periods—all of these being variously in evidence. Added to them is now a strata of aggressive multinational initiatives, IMF and World Bank imposed stringencies, and the exigencies of boardrooms and homeoffices perpetually in pursuit of new markets and the cheap labor that is the elixir of India’s middleclasses, the summoning finger of its politicians, and the invisible ballast of faraway consumers buoyant with credit. Scarcely twenty years into India’s “liberalization,” the results are already clear enough: the gap between its richest and poorest citizens has grown dramatically, and is nearing that of the United States—which remains the model of strapping enterprise and income inequality in the “developed” world. In effect, India is not so much a singularly underdeveloped nation as a microcosm of development and underdevelopment worldwide.

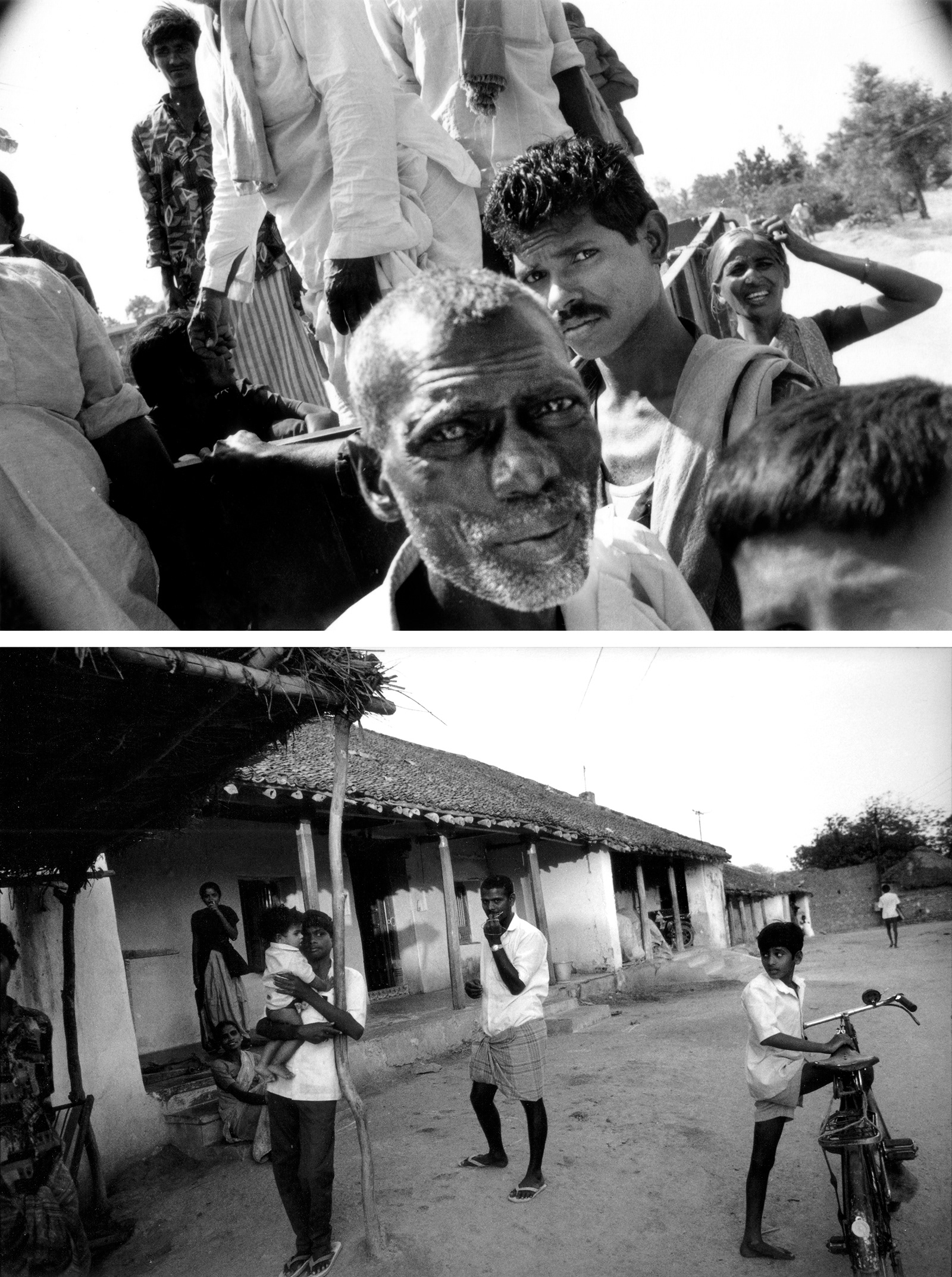

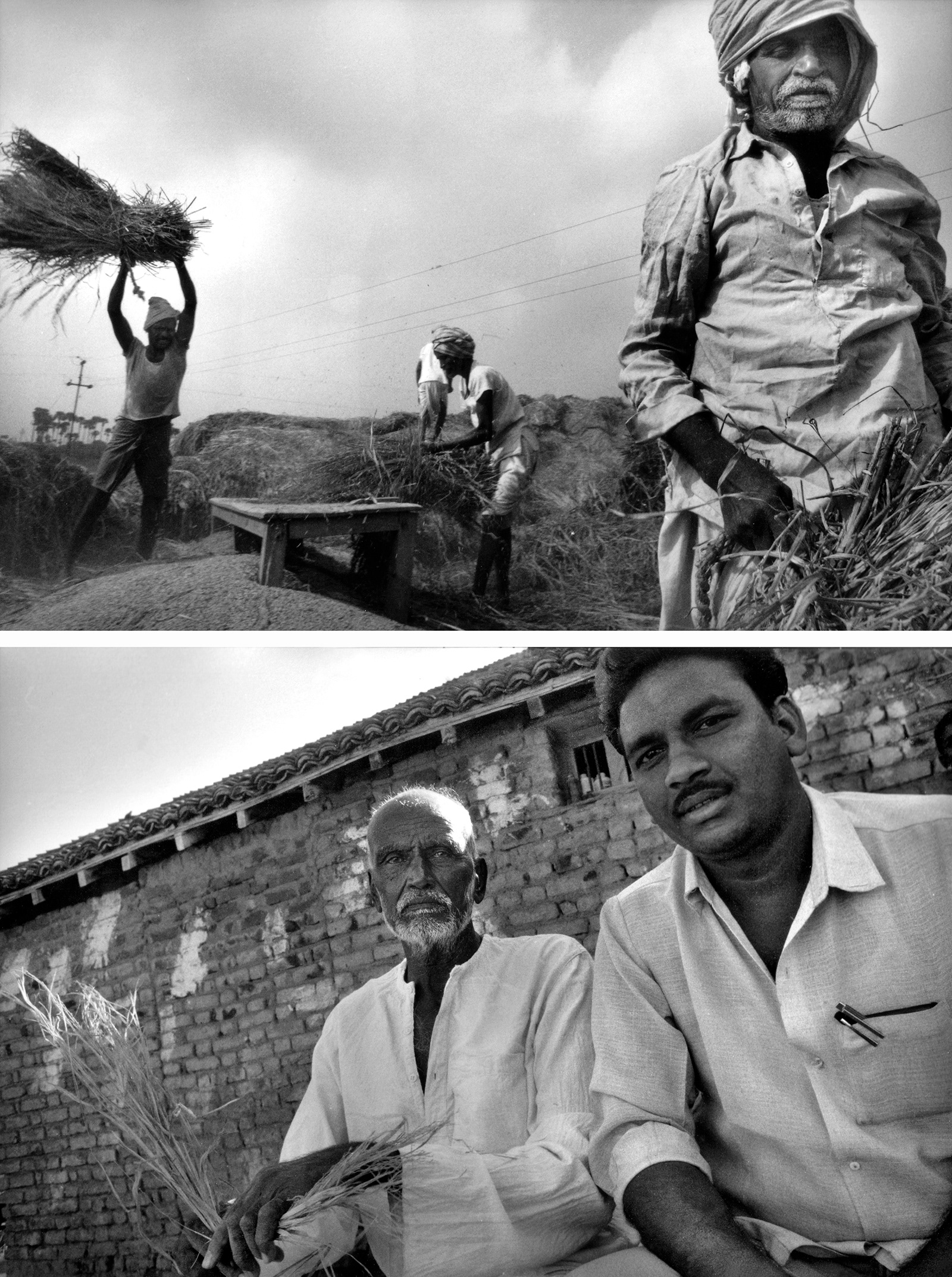

Fifty kilometers up India’s National Highway 9 from Vijayawada toward Hyderabad is the town of Nandigama, with a population of 25,000, a hub for the sixty or so villages within a 25 kilometer radius. To arrive in Nandigama is to enter Telugu desham, the heartland of southeastern India: one small and vast corner in the peripheral realms of our “global” world.

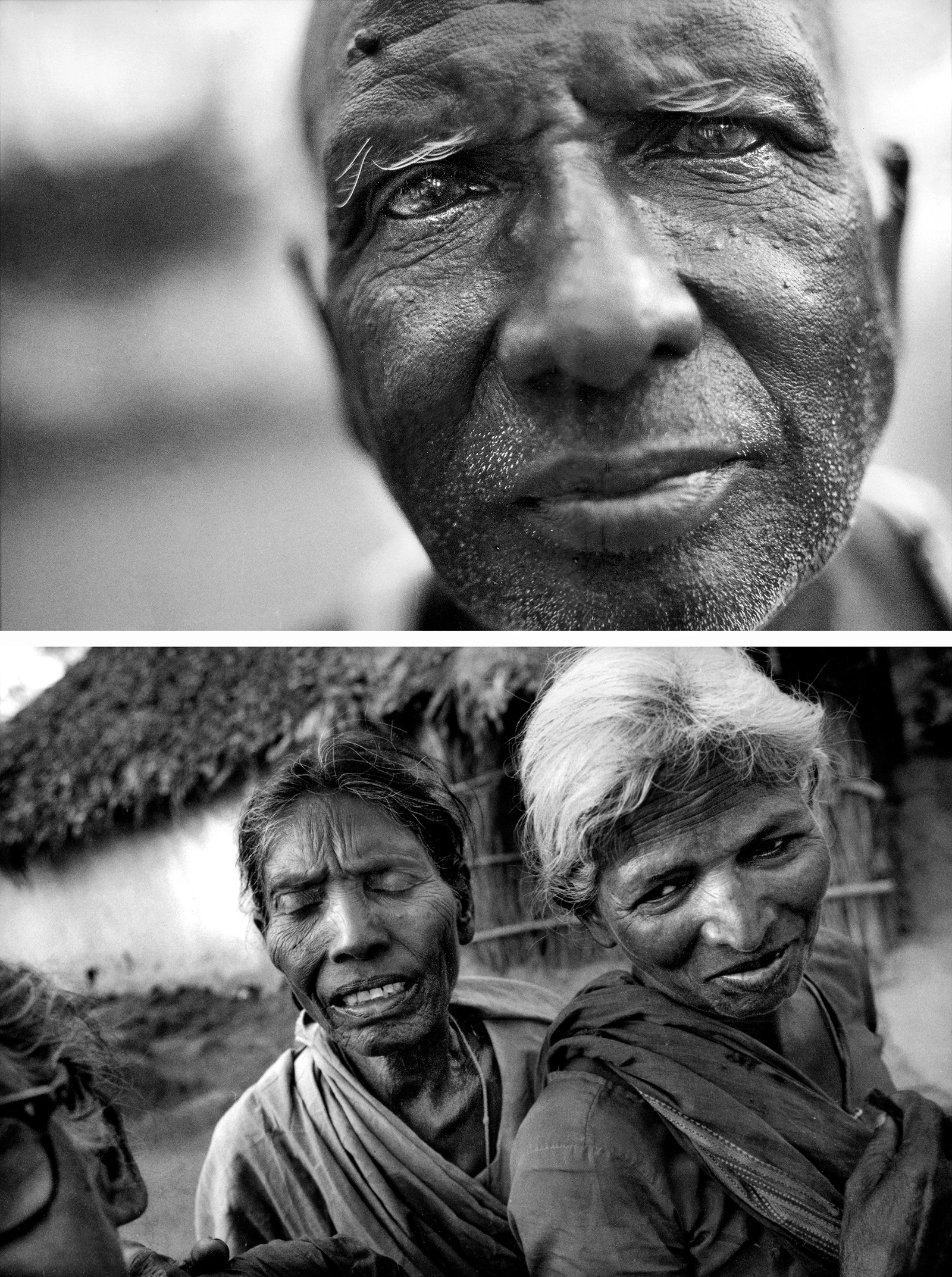

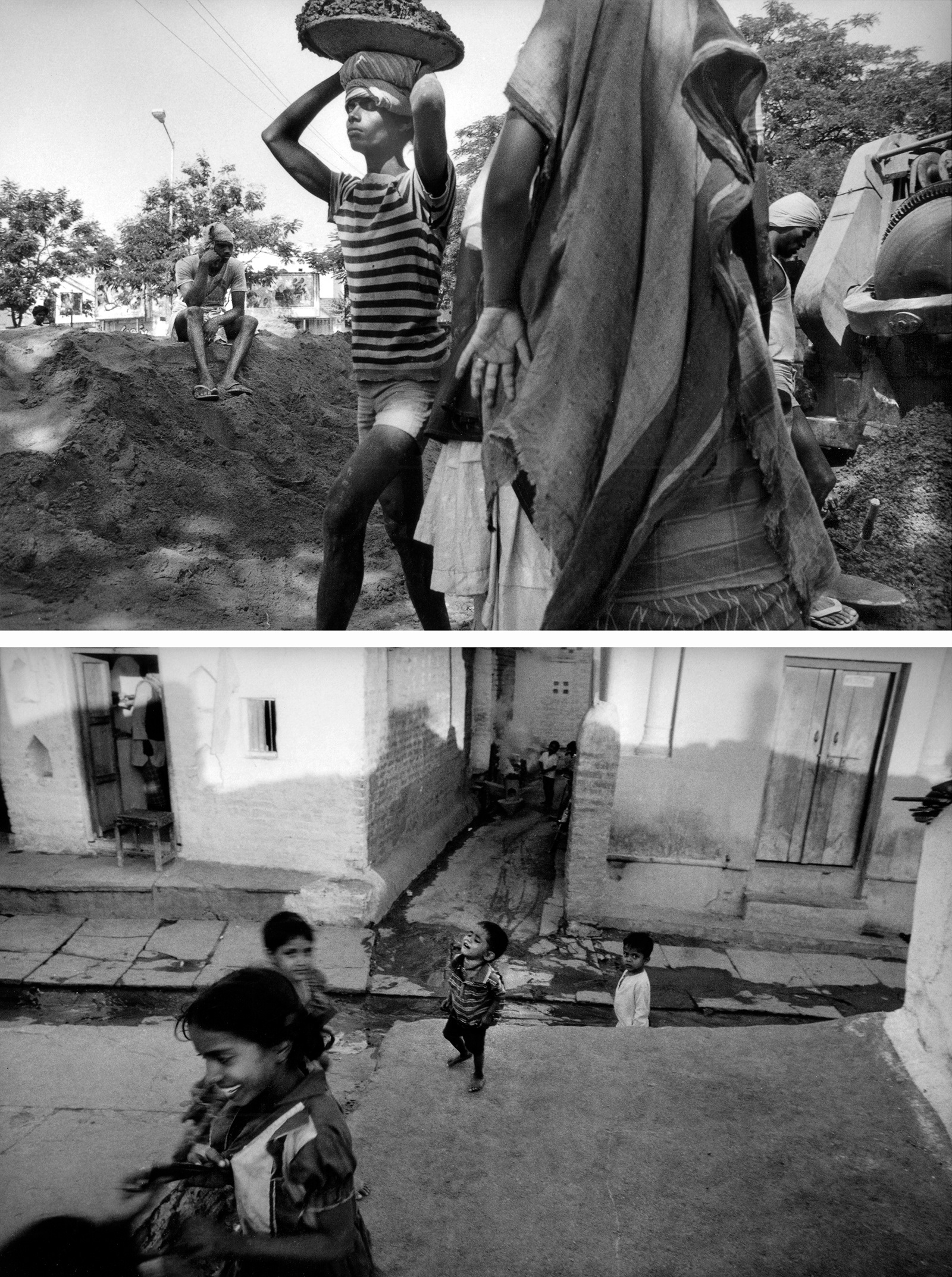

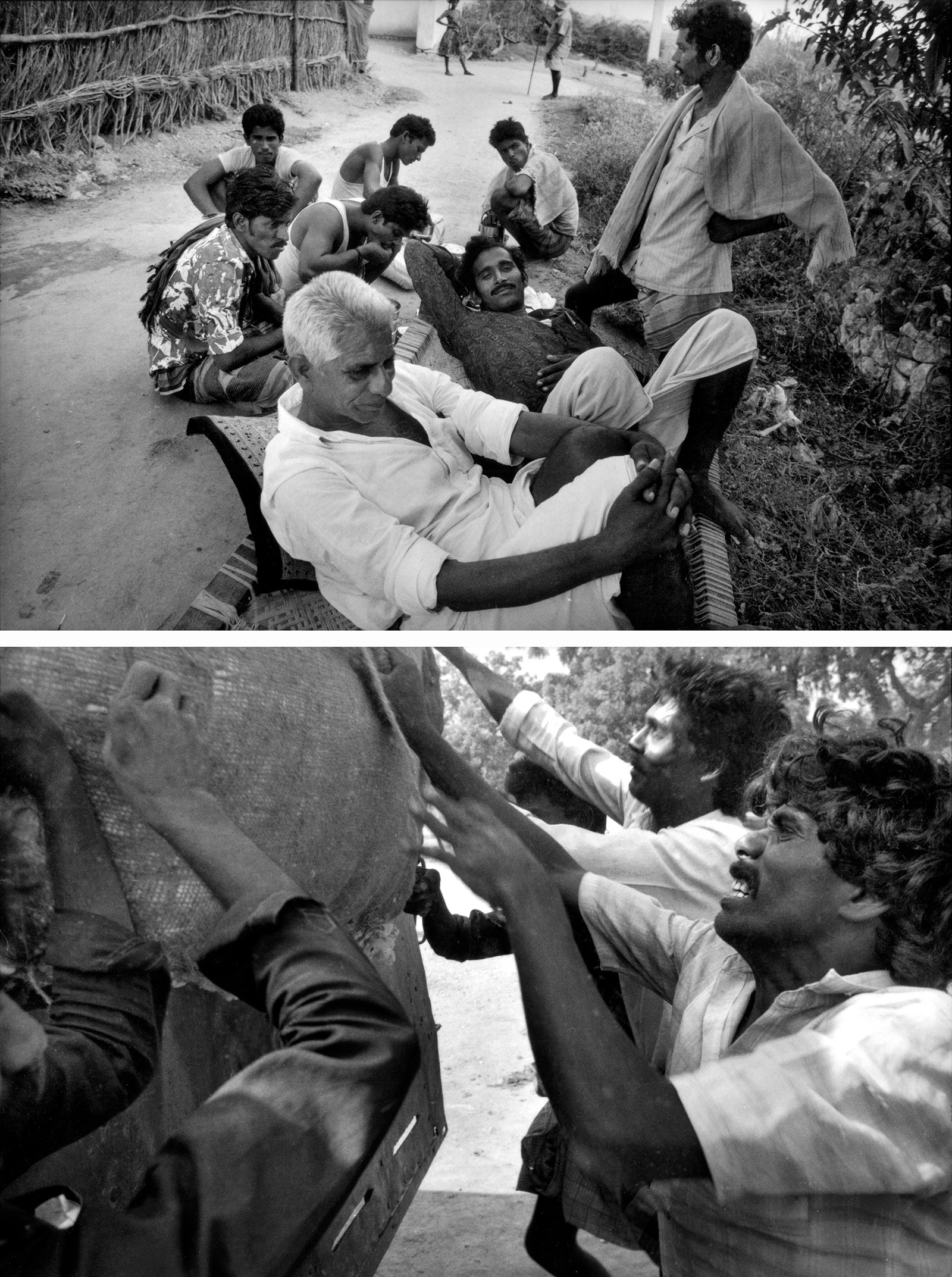

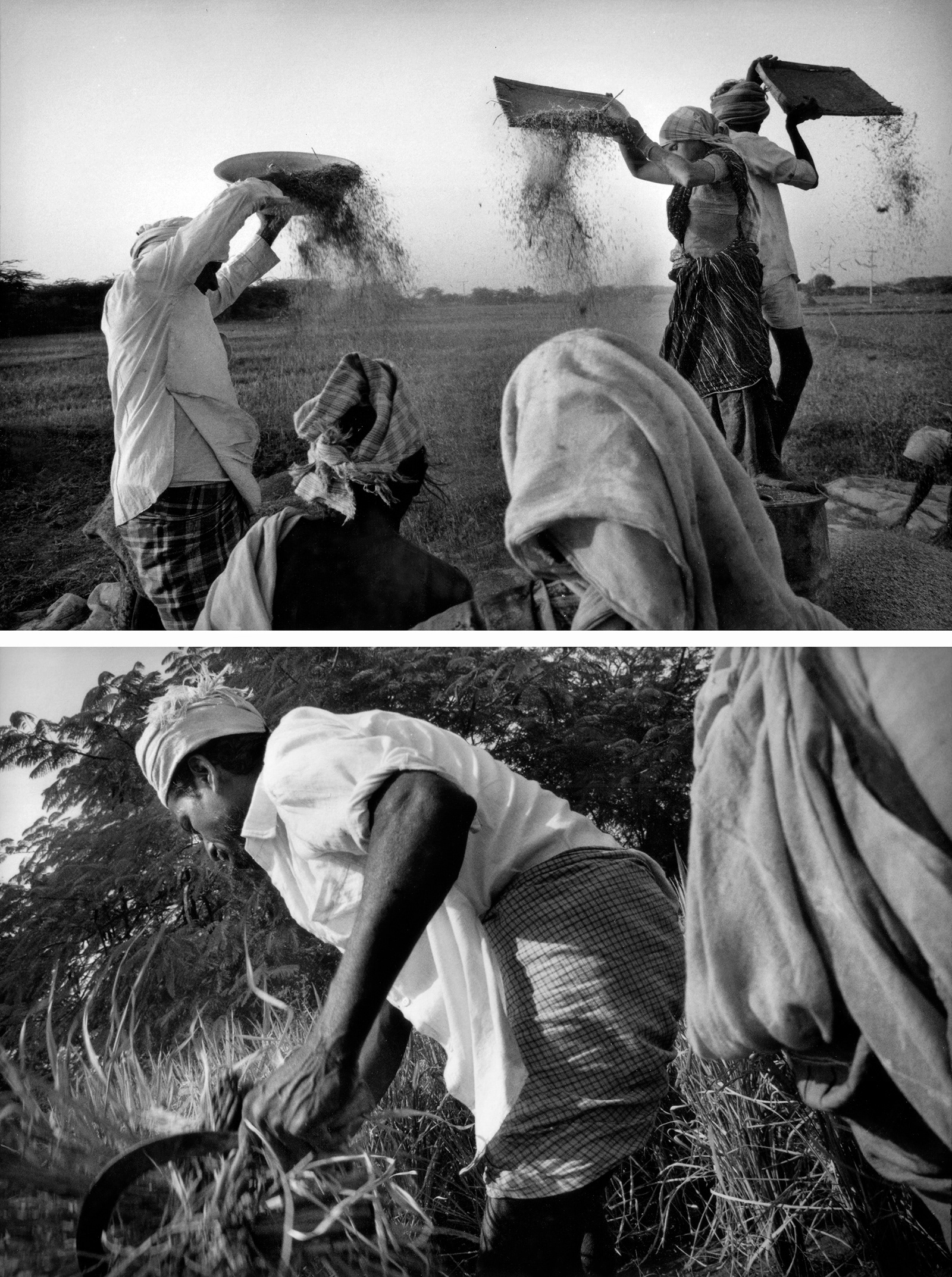

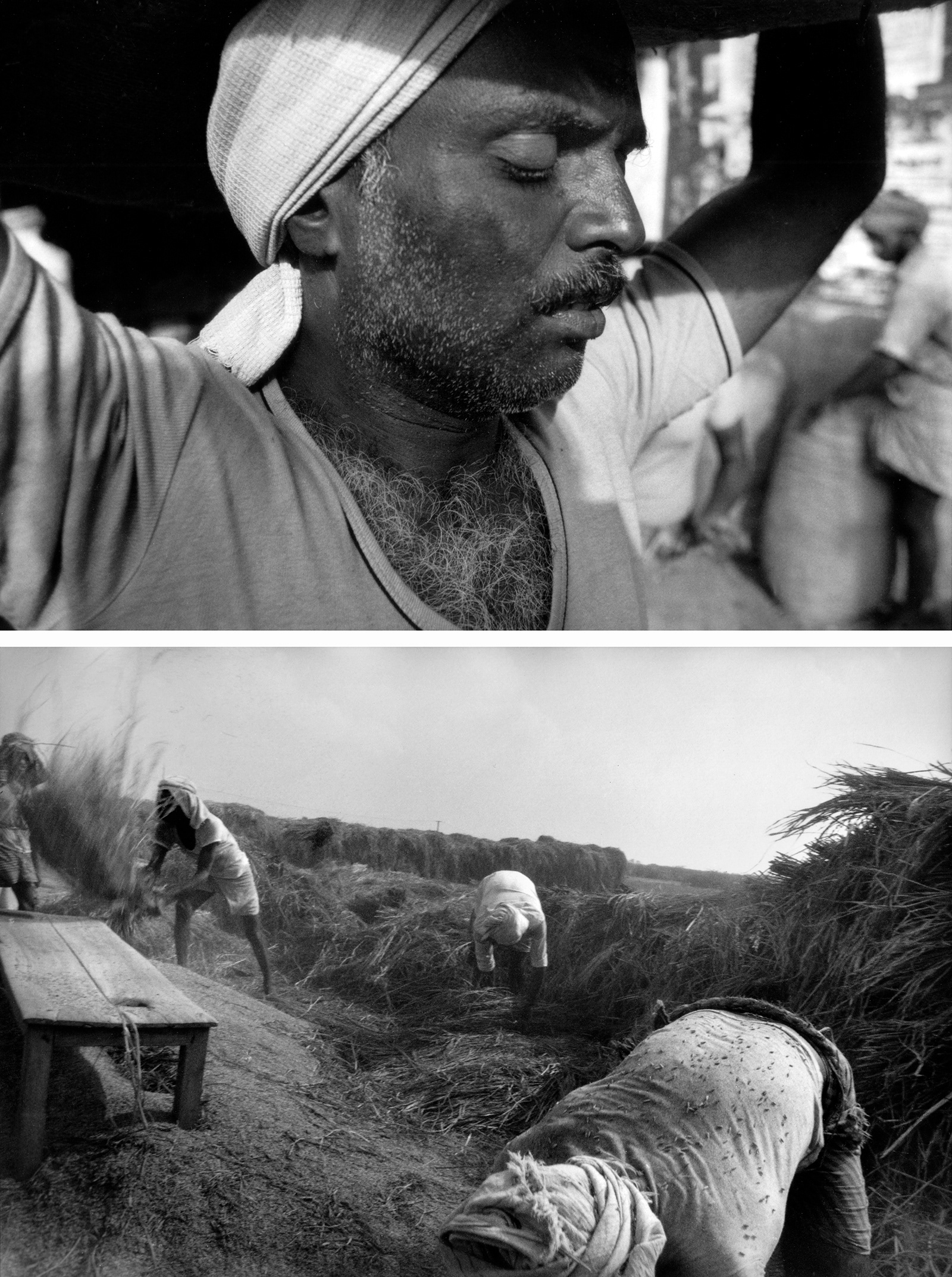

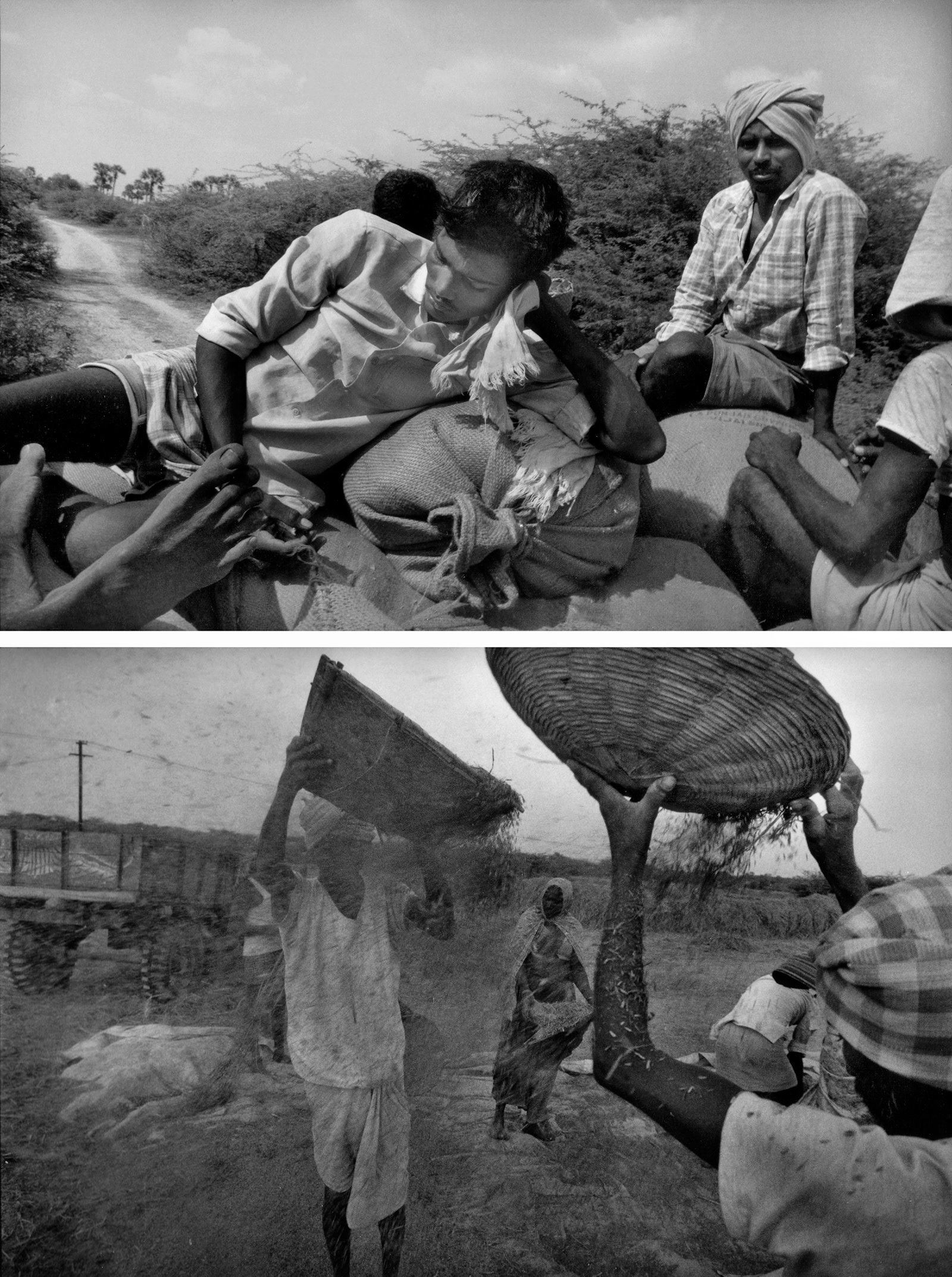

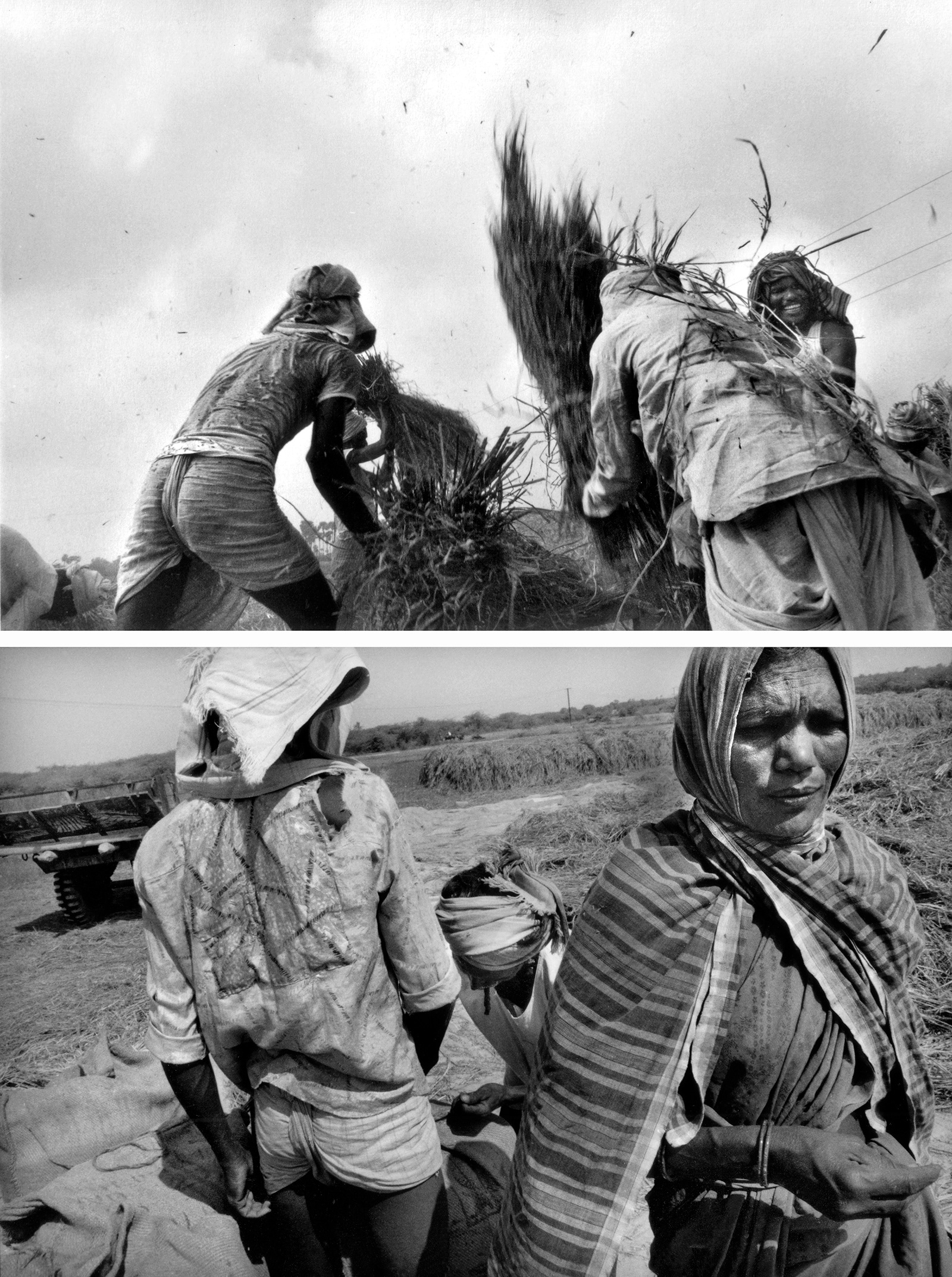

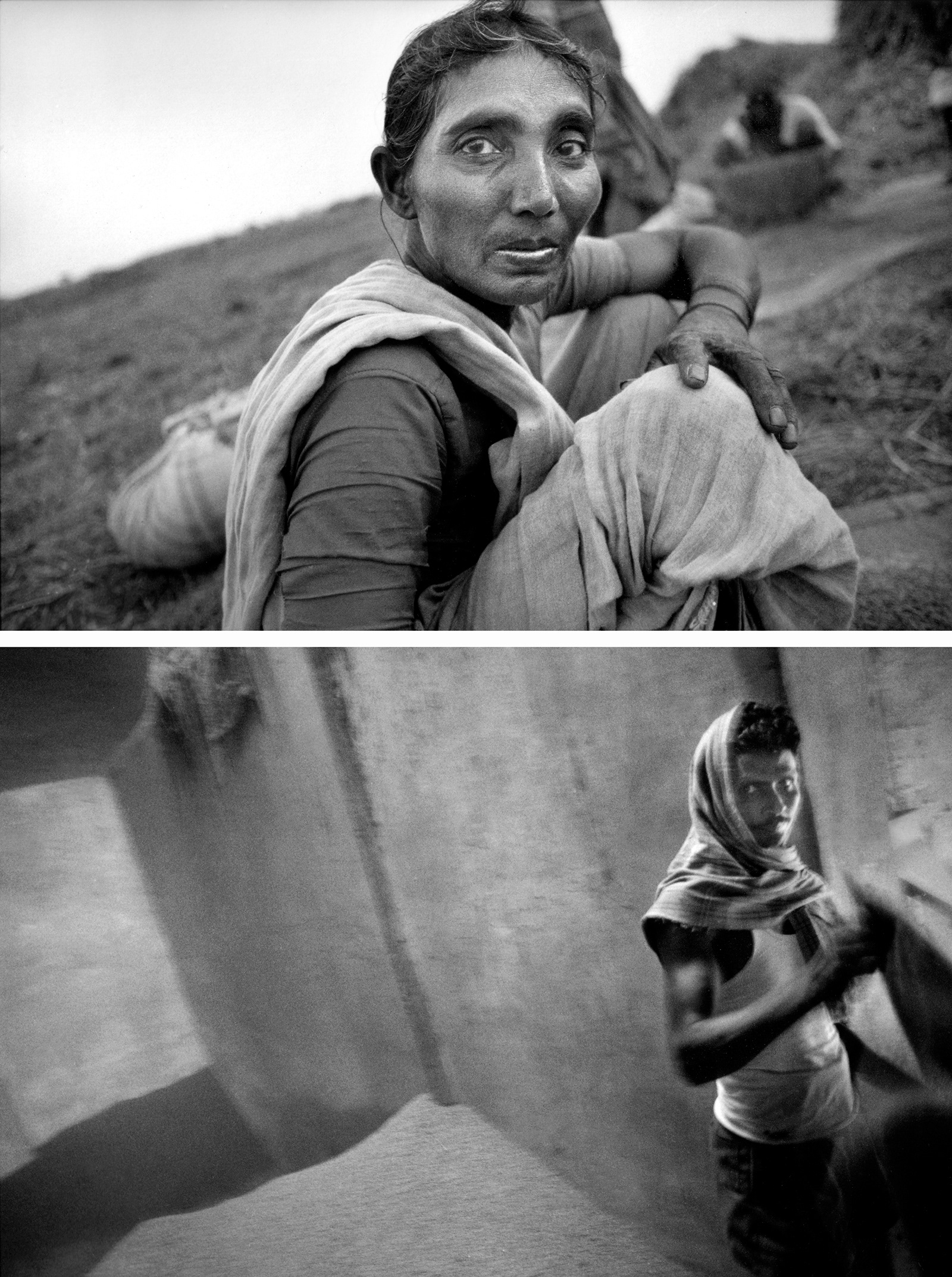

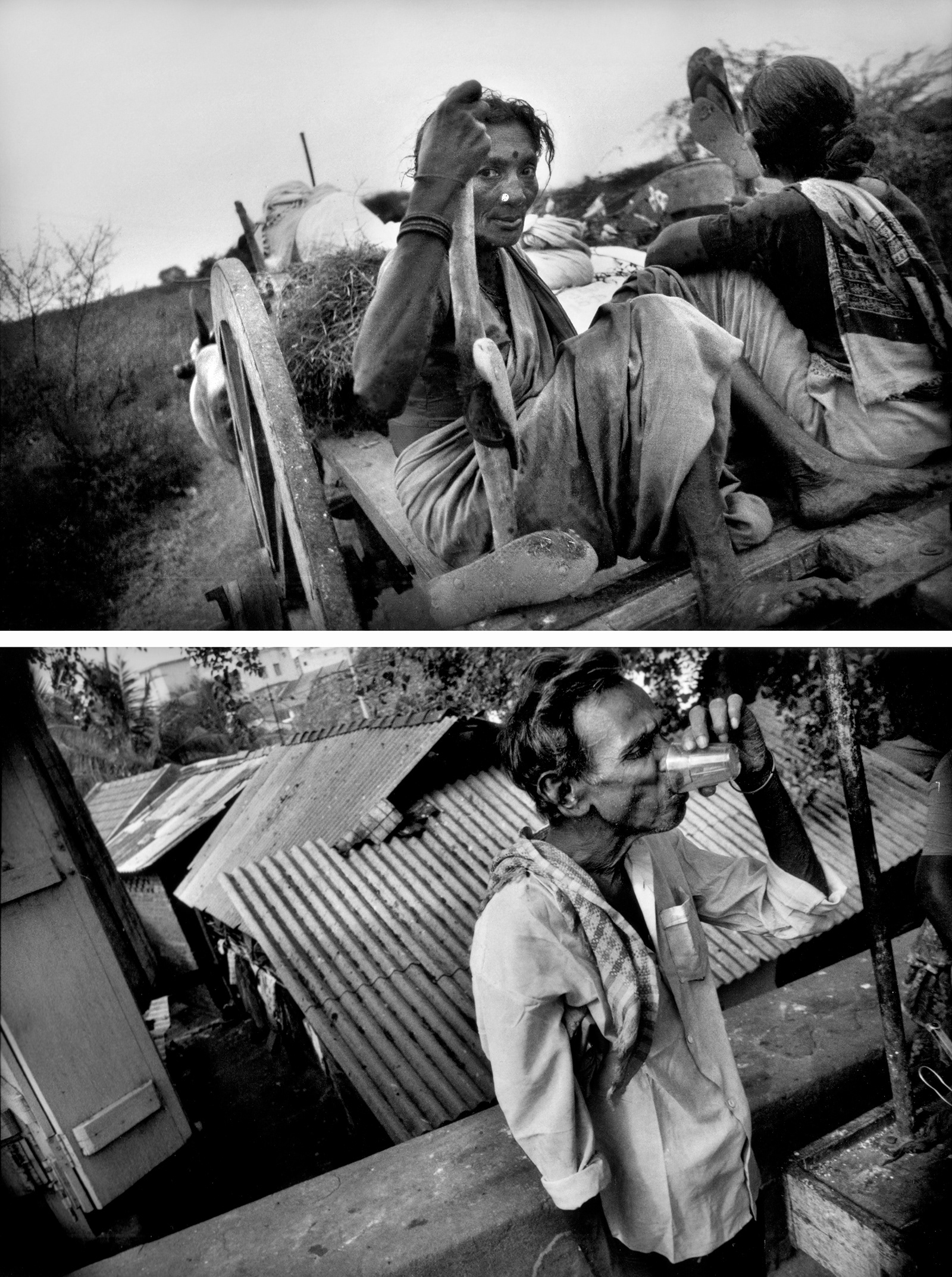

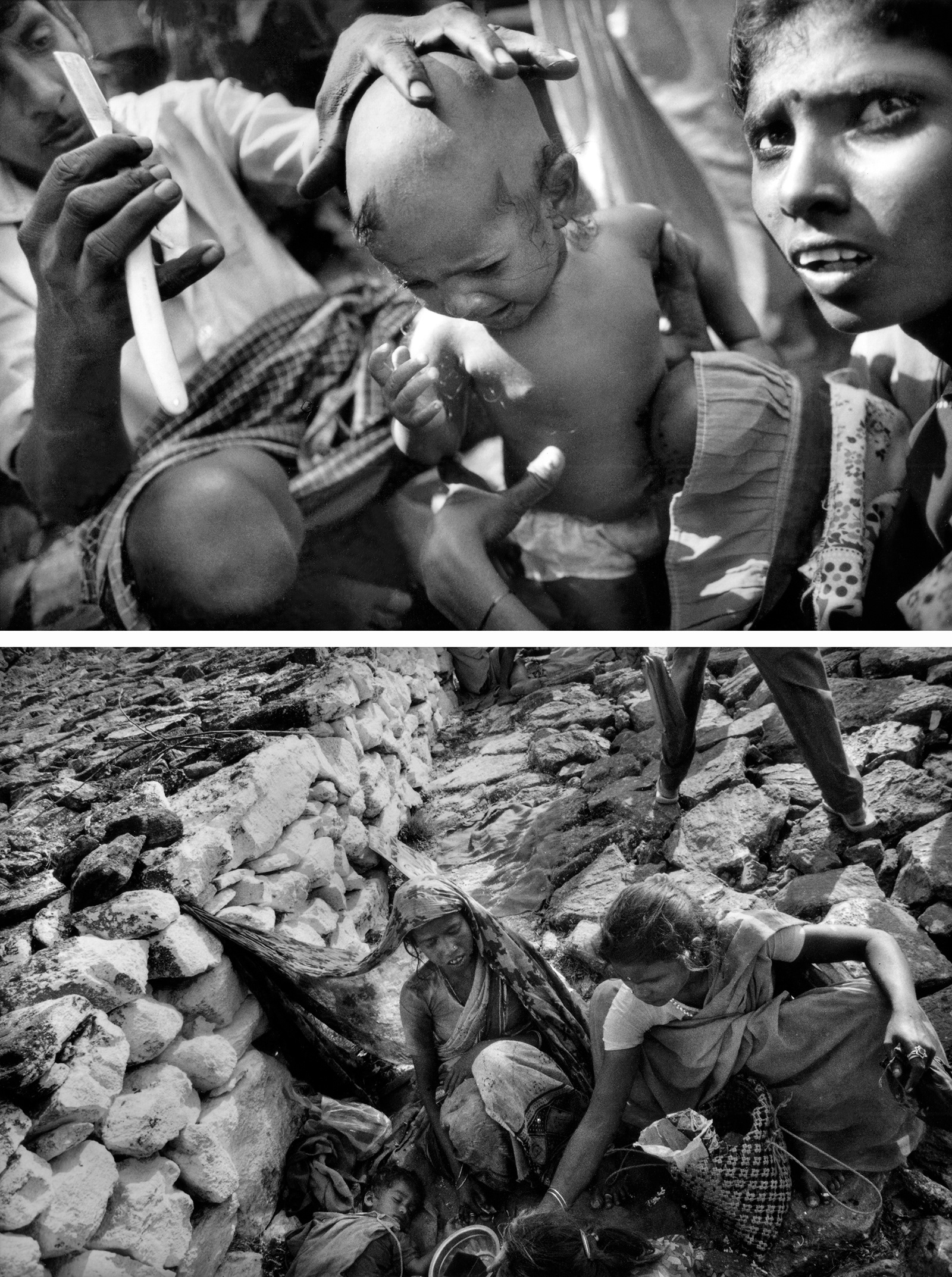

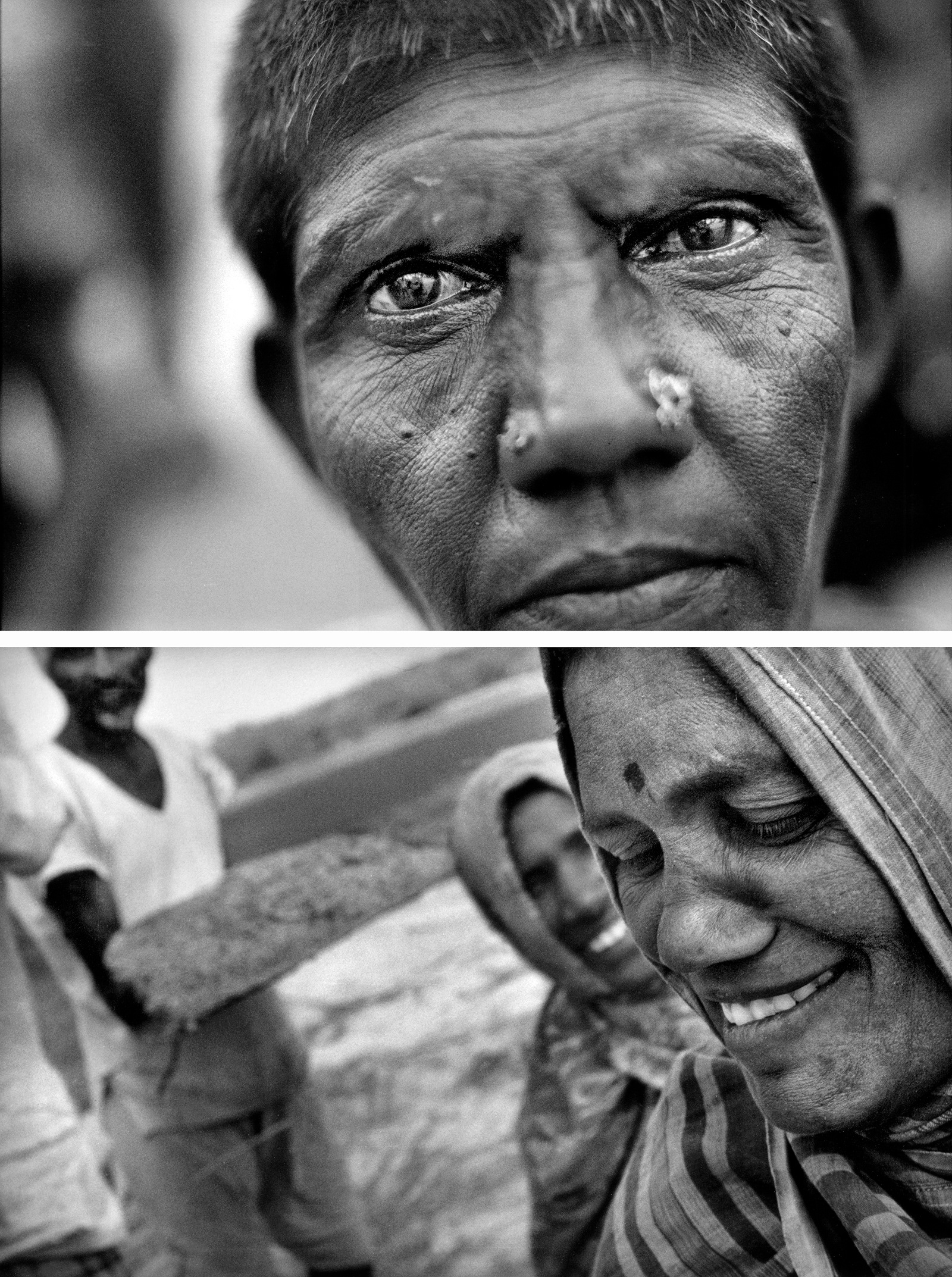

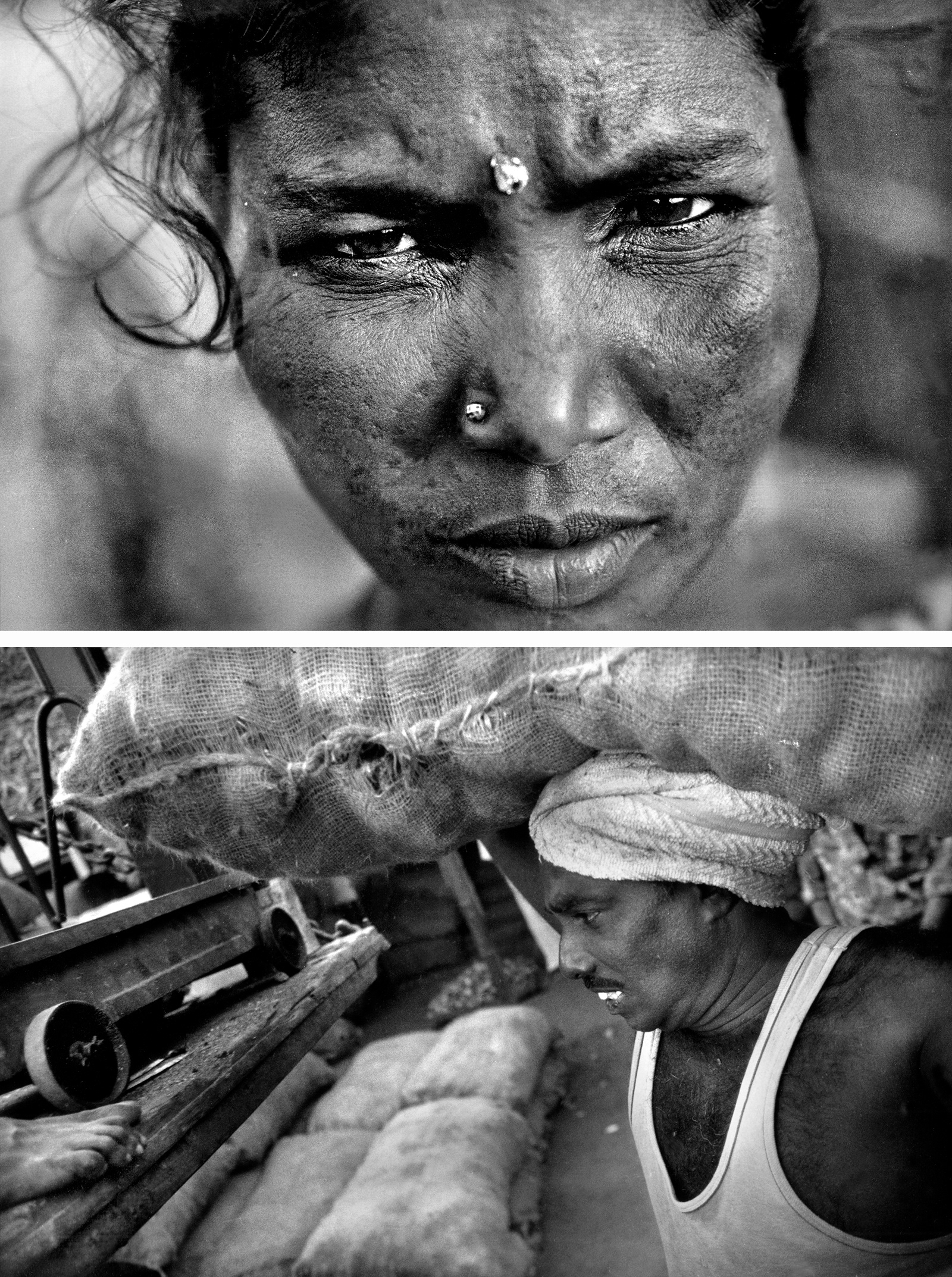

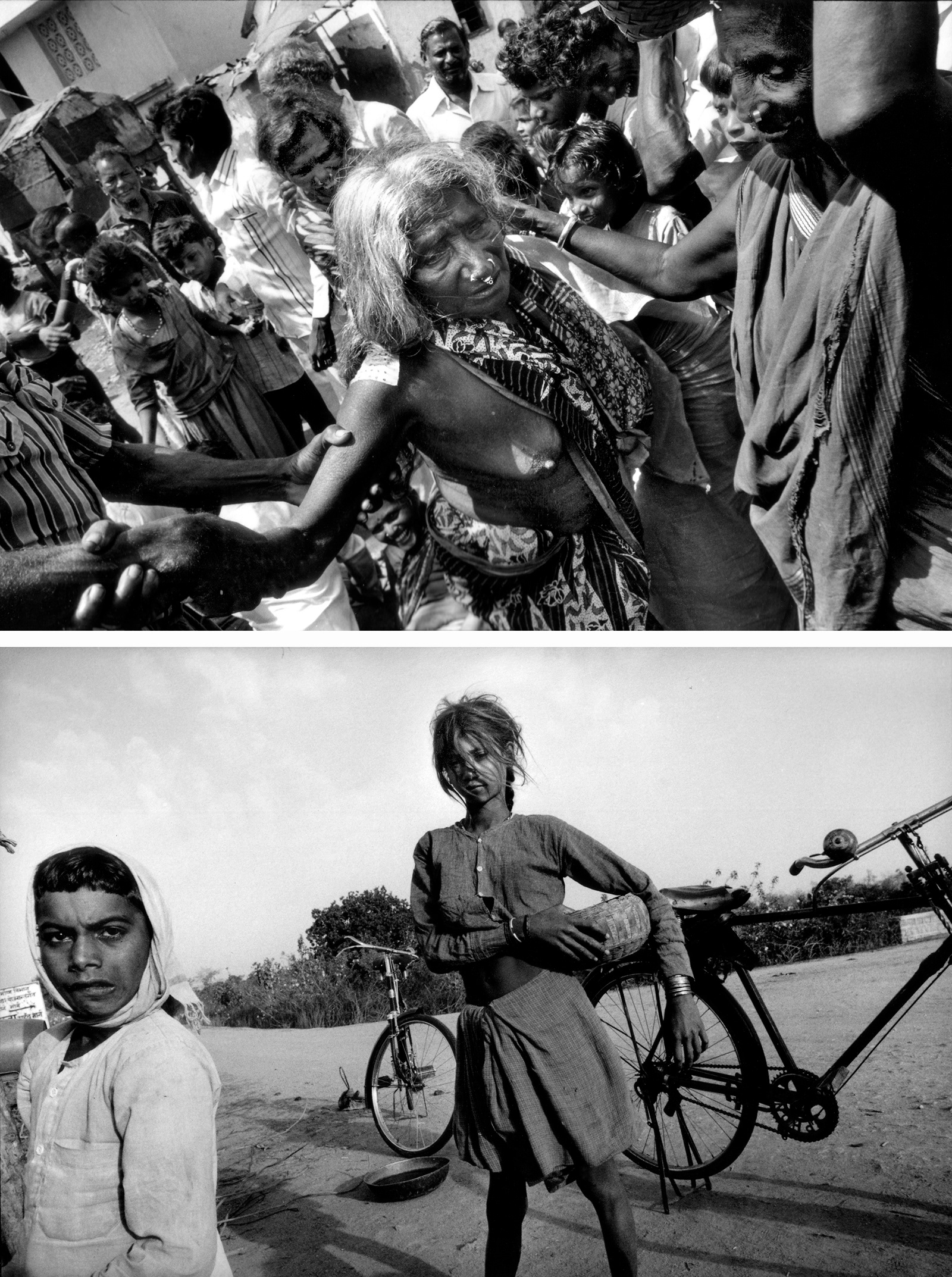

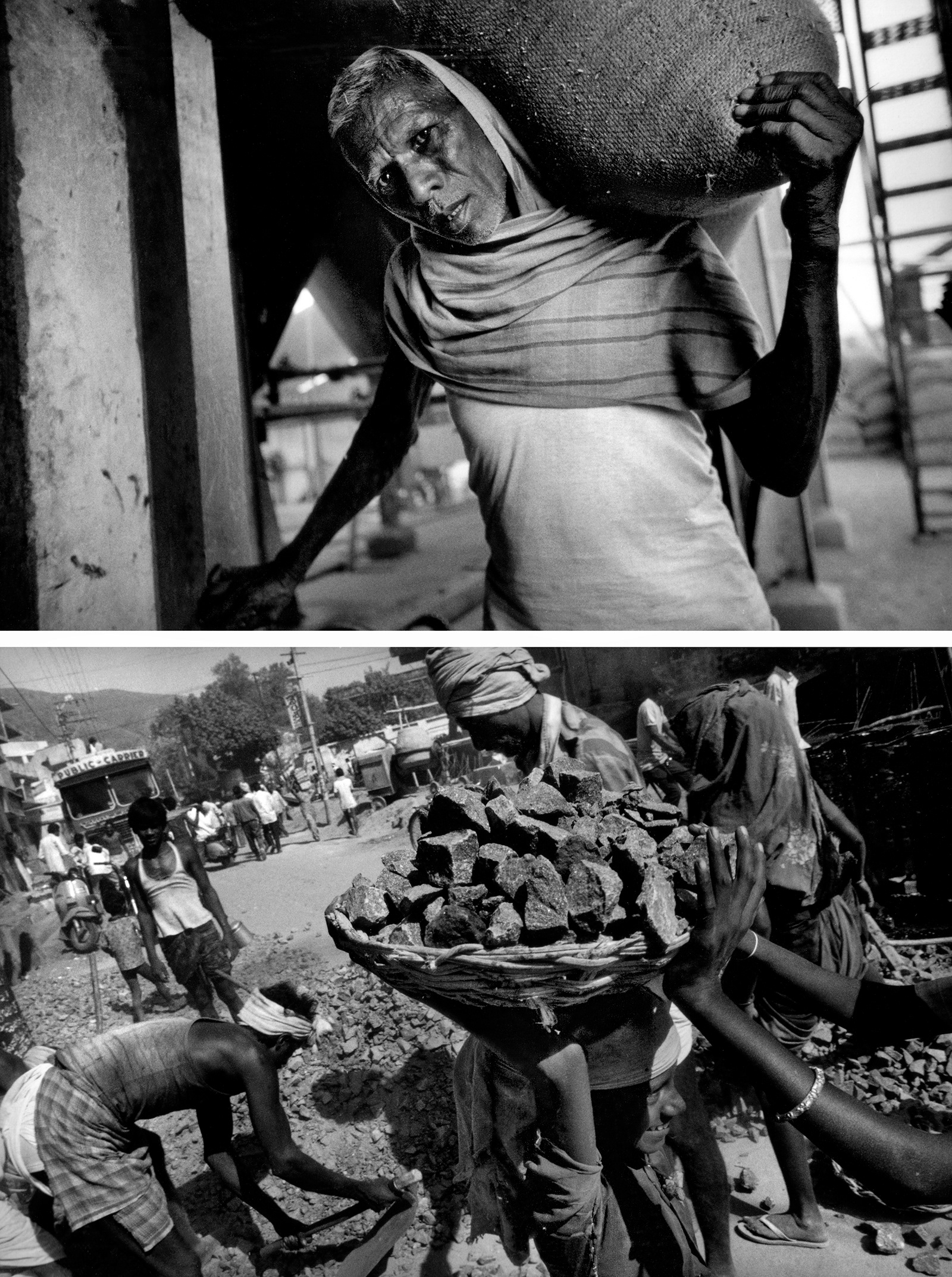

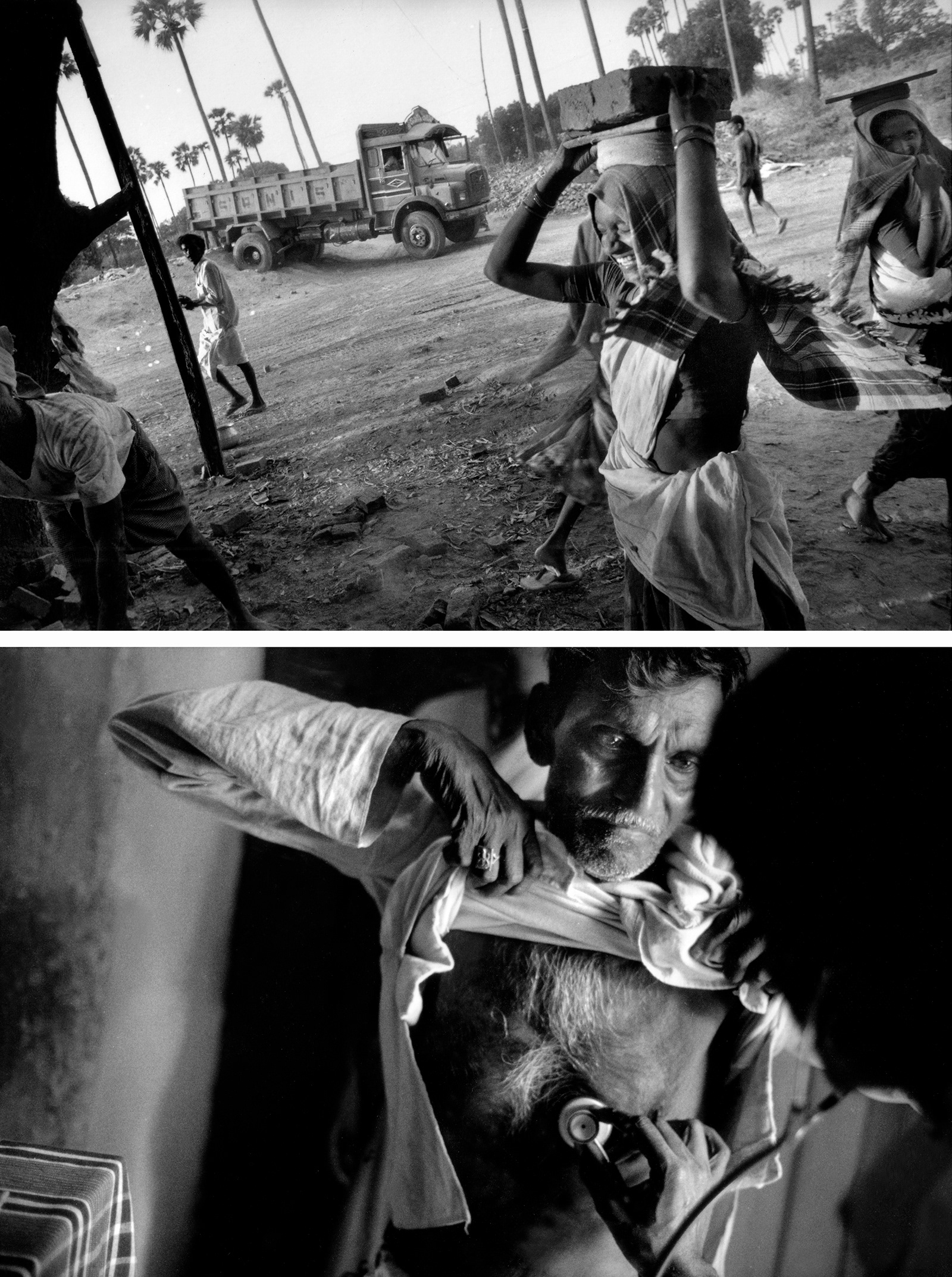

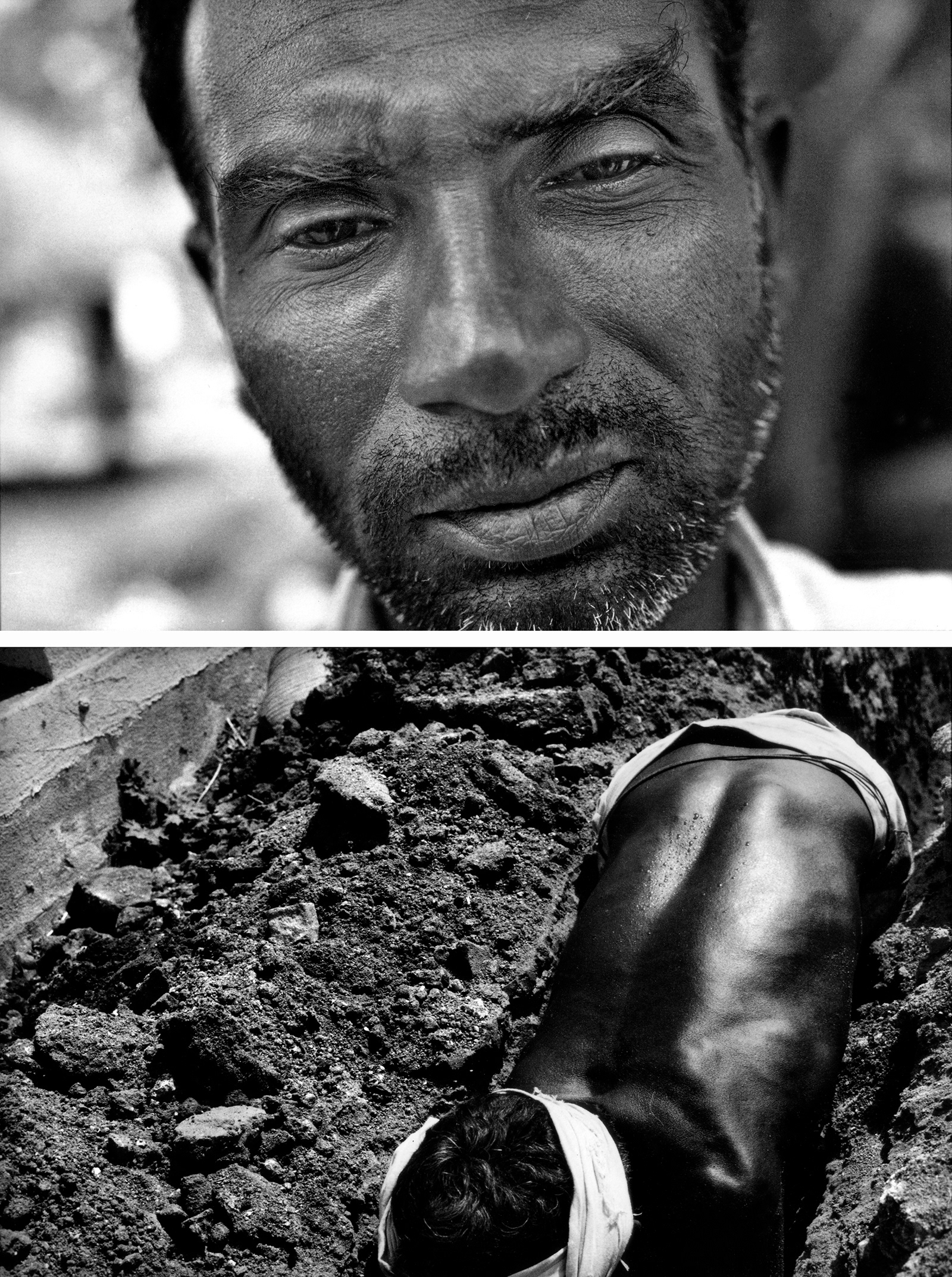

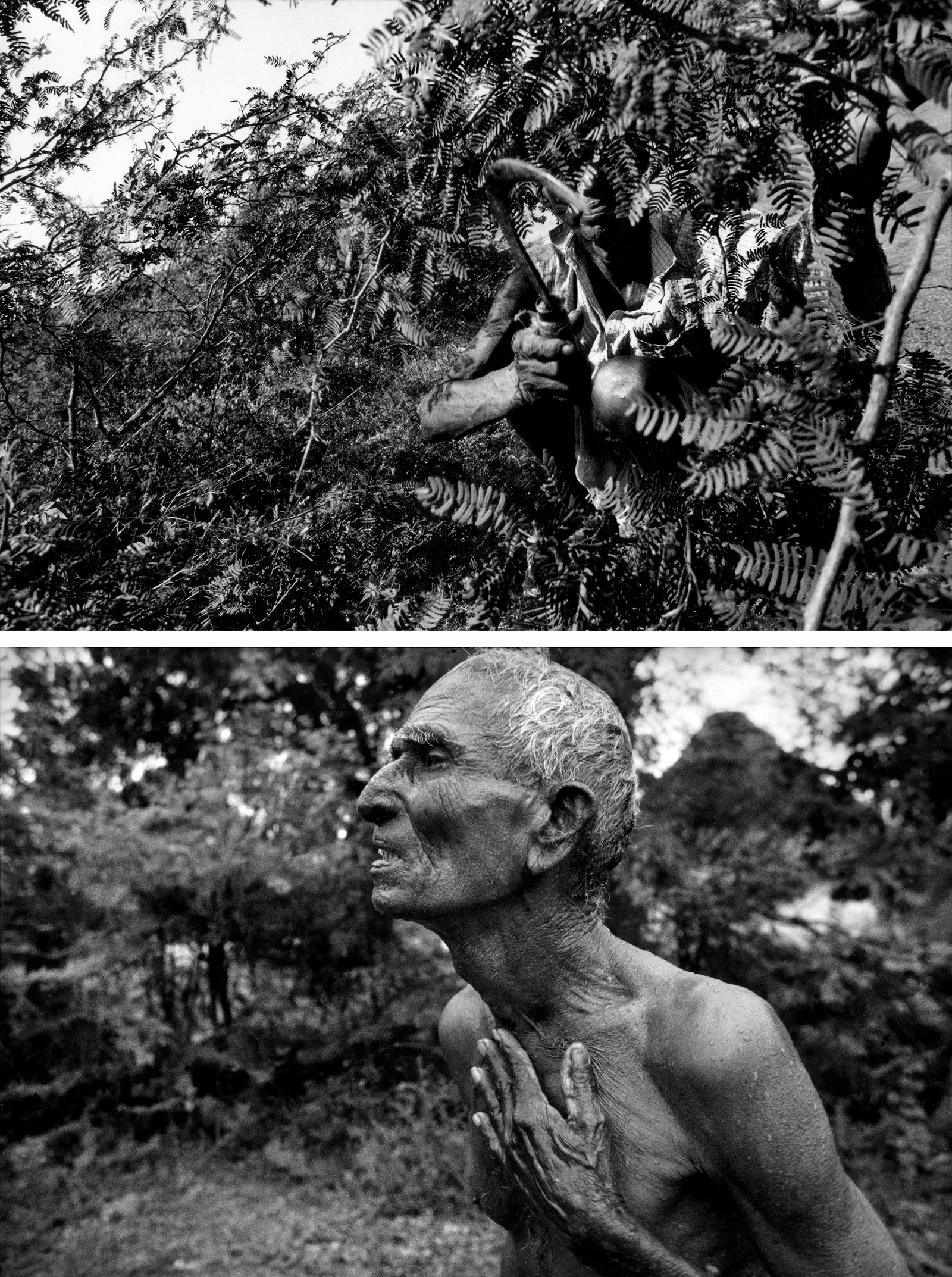

Punnavalli, Senagapadu, Muppalla, Ramanapeta, Kammavaripalem, Chandarlapadu, Monagacherla, Kanchela: to step into these villages, these plaincountry destinations, these deeply originary points—uurulu in the Telugu language—is not to enter places built up from premeditations for prosperity. Telugu desham: dry, scrubby, arid. To sustain it as a home is continuously and unrelievingly to struggle—to give and to lay, to plant, to chop, to haul and to lay by. To sustain it: to be joined into the labors that fuse rain and dirt into luck, and into the praise and blame by which bloodlines are guarded and shared, and into the signal movements idly and cruelly and lovingly of parturitions and festal steps and rumors of justice lurking somewhere at sullen heights. What is it to inhabit these places? Not belonging is never really considered.

And on the periphery of the periphery, on the backsides and away from the villages: the settlements of the marginal peoples of the countryside, the so-called untouchables or Harijans, or more plainly, kuli pani chésé vallu, “work-made people” as the Telugu language knows them—the fifty percent of the rural population in and through whose toil the local economy is built. These settlements by these villages: the remotest rings around the metropolitan centers of our world.

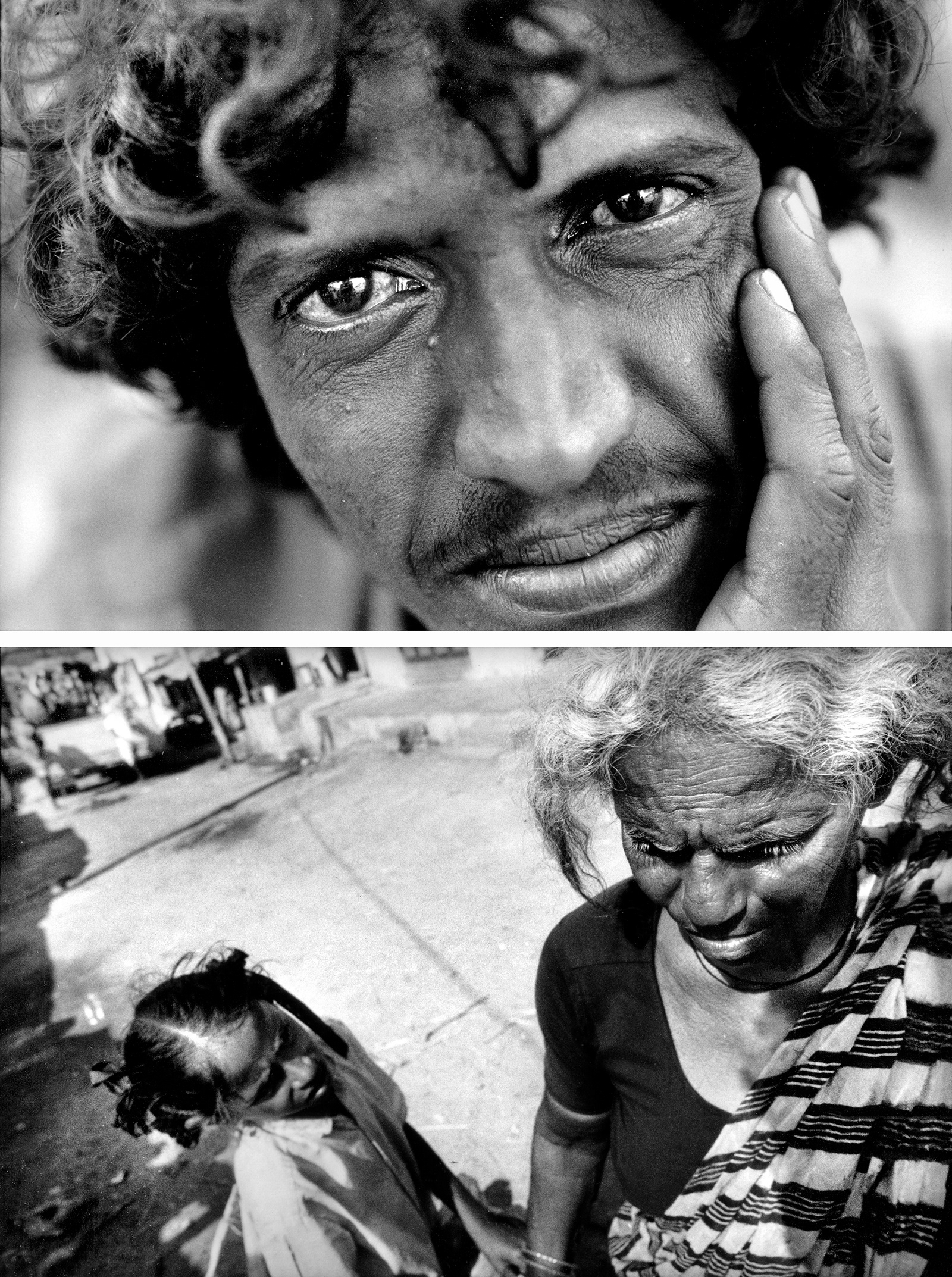

Predicament: How to make the villages in the book? For the eyes and the legs and the lungs, the villages are given. They are not made or unmade. They do not begin and do not end. They are neither complete nor incomplete, neither true nor false. Rather they are entered and left, remembered and forgotten.

But in the book, the villages must be made.

I ask myself: how to communicate the wholeness of life in the Indian countryside—the processes of actuality, social, economic, religious—as these inform and offset each other? How to make words and pictures interrogate each other with open-eyed and not-sublime immediacy, sometimes intersecting, sometimes paralleling one another—toward a dialogue of complementarities? Or to ask another way: are the villages to be constructed from nothing—word by word, picture by picture? Or are they to be derived through words and pictures from their totality beyond all representing—every word and every picture a fracture point through which the villages re-enter life through the book?