At the six-month anniversary of October 7, 2023, Peter Habib and I began a project that we call “These are the Names,” in which we publicly say the names of those killed in Israel and in Gaza since October 7th. The project took place on and around the quadrangle at Emory University in Atlanta, where Peter is a Ph.D student in anthropology, and I am a faculty member in visual arts.

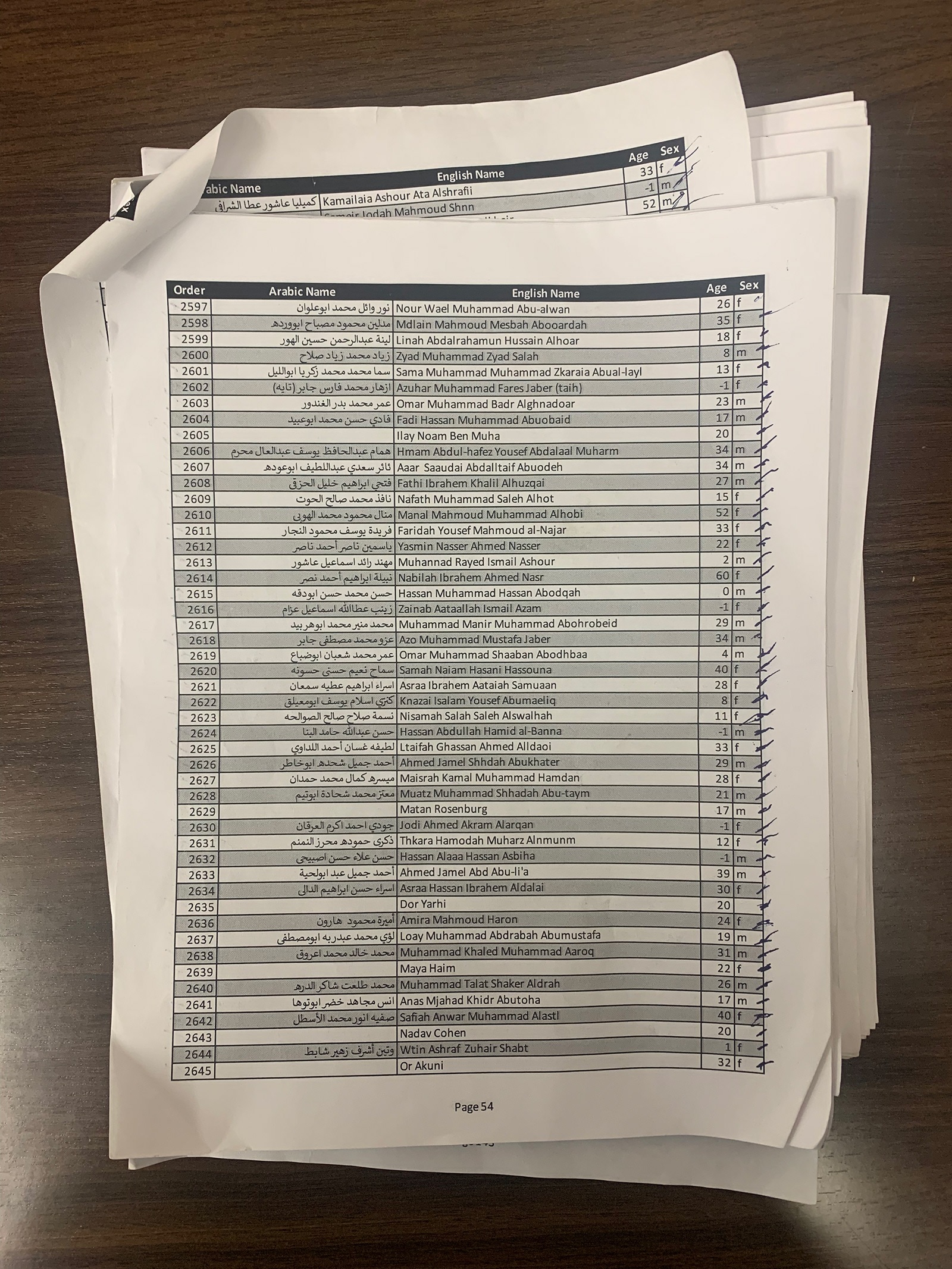

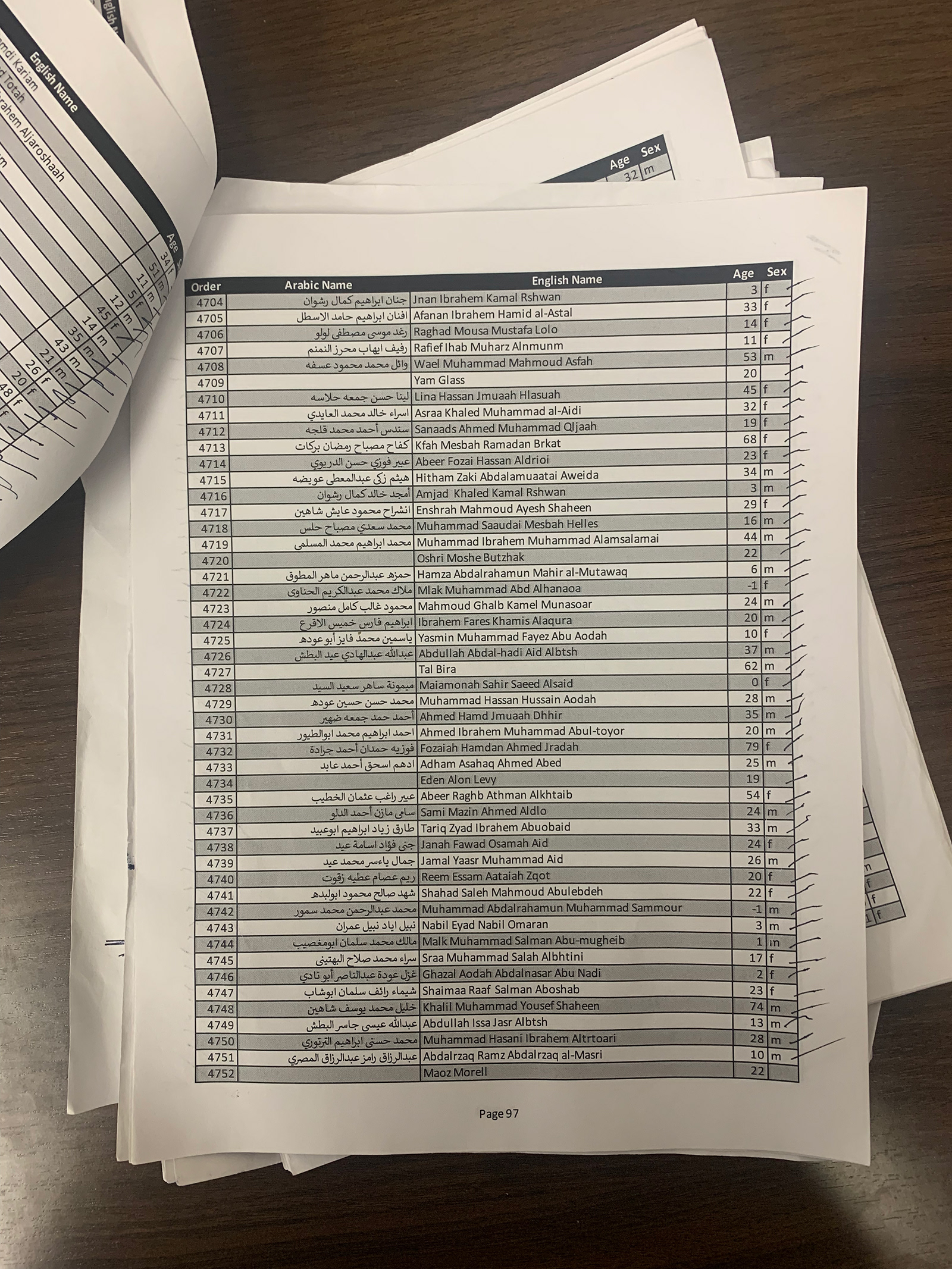

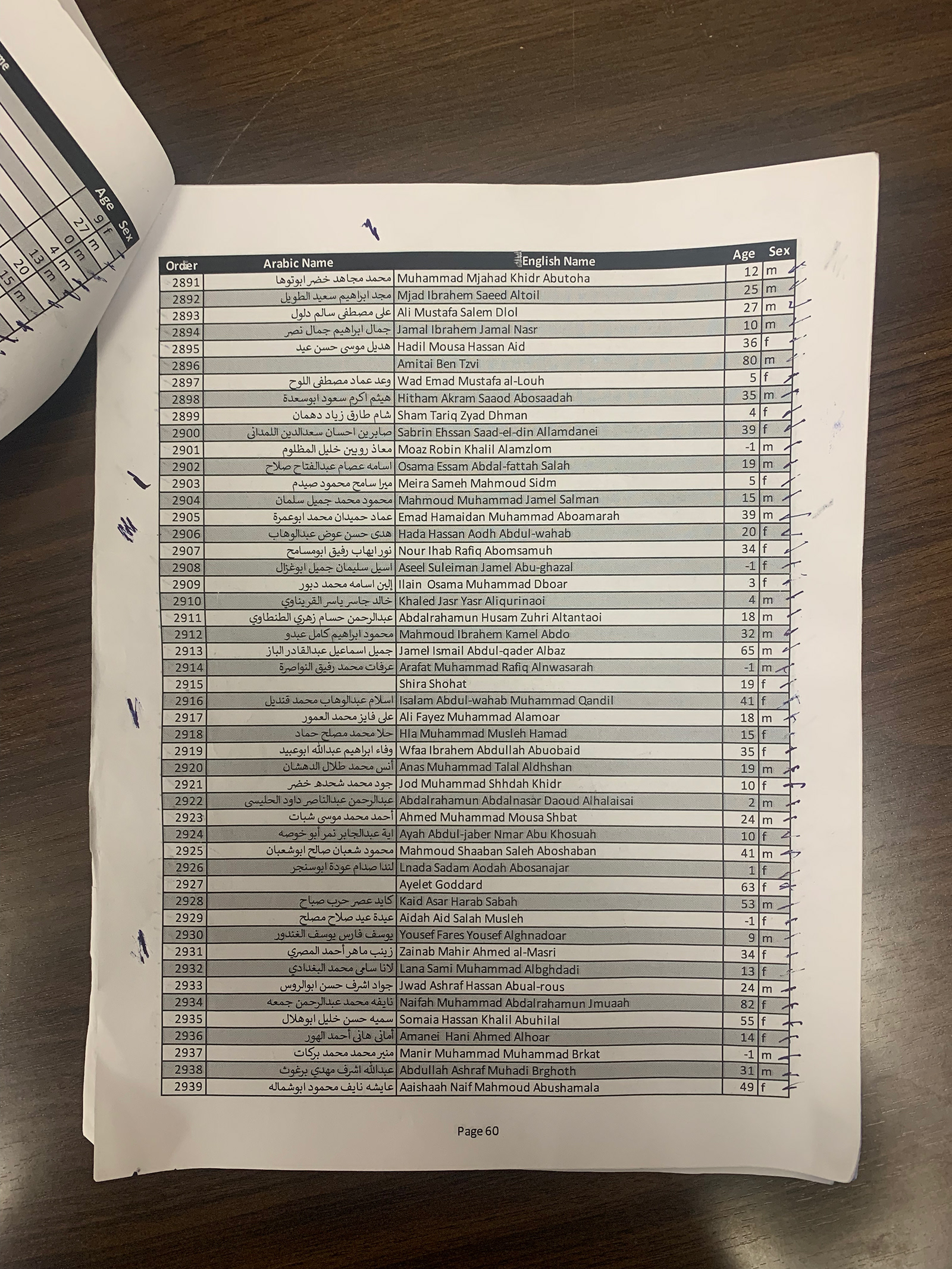

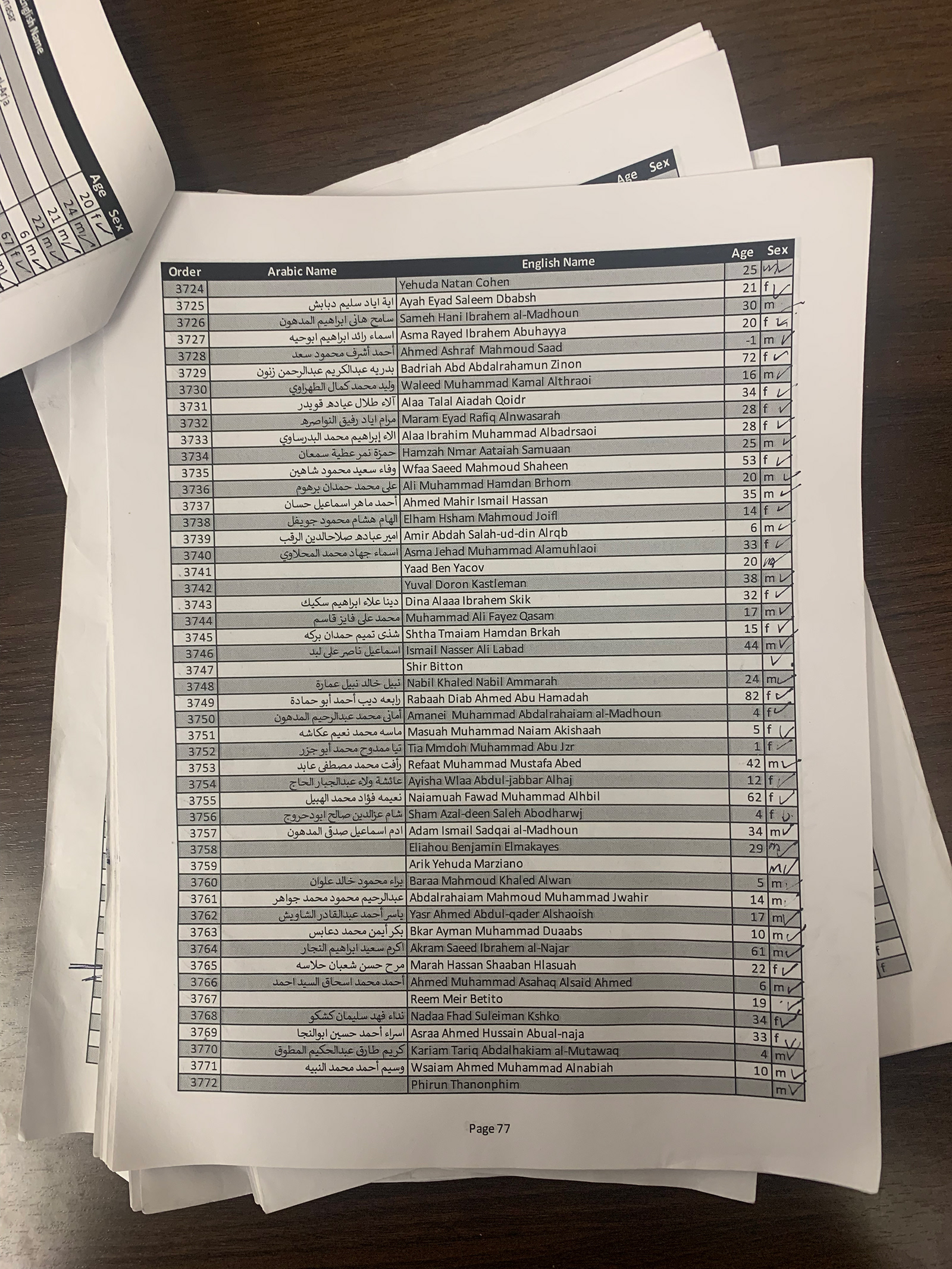

Hour upon hour, we have said the names of the dead, person by person, from both sides of the conflict, along with the person’s age. After each name we strike a drum, and sometimes ring a bell. The order of the names is randomized. There are no speeches. Every fifty names or so, we pause to explain what we are doing in the simplest terms possible, generally like this:

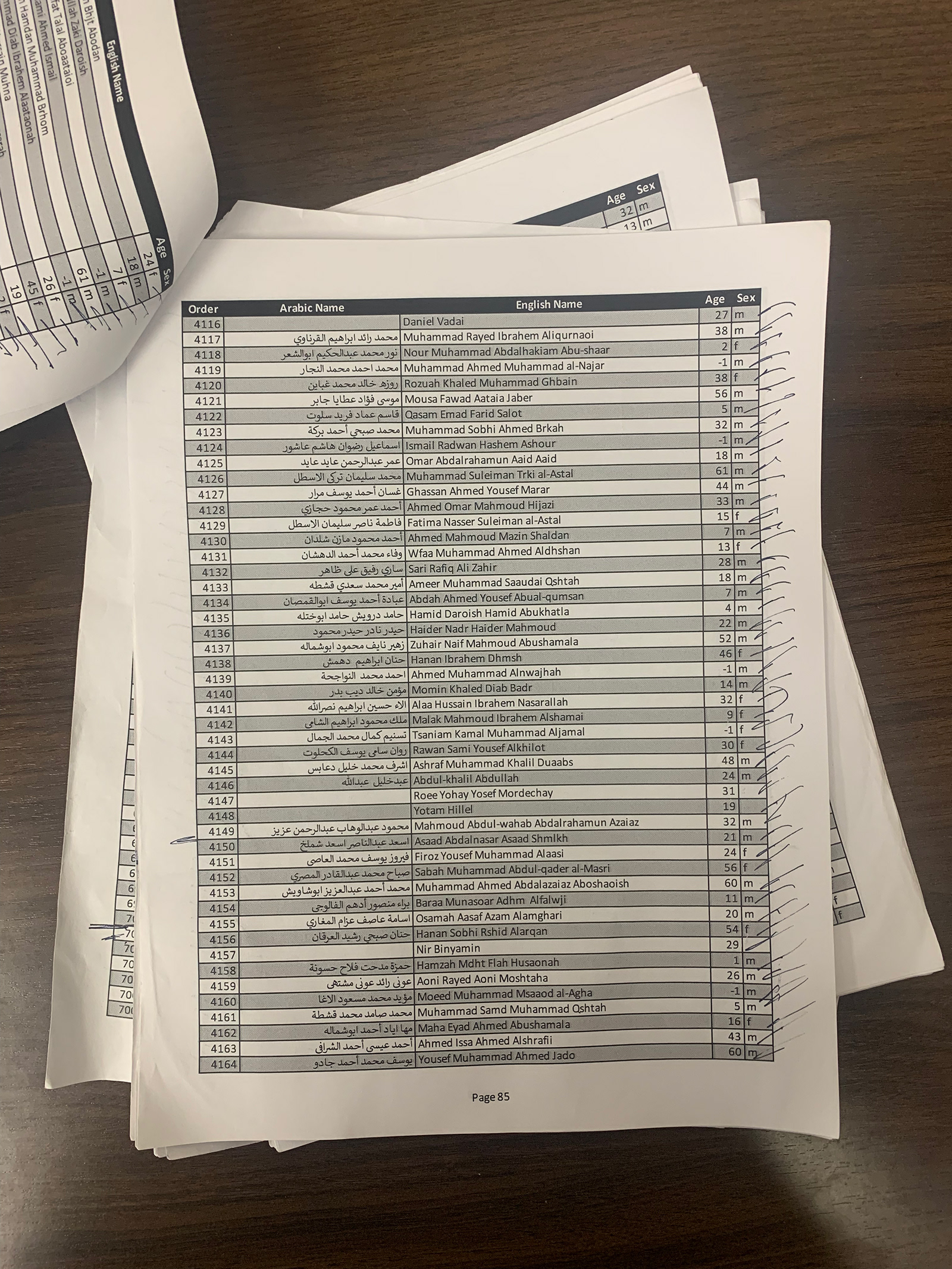

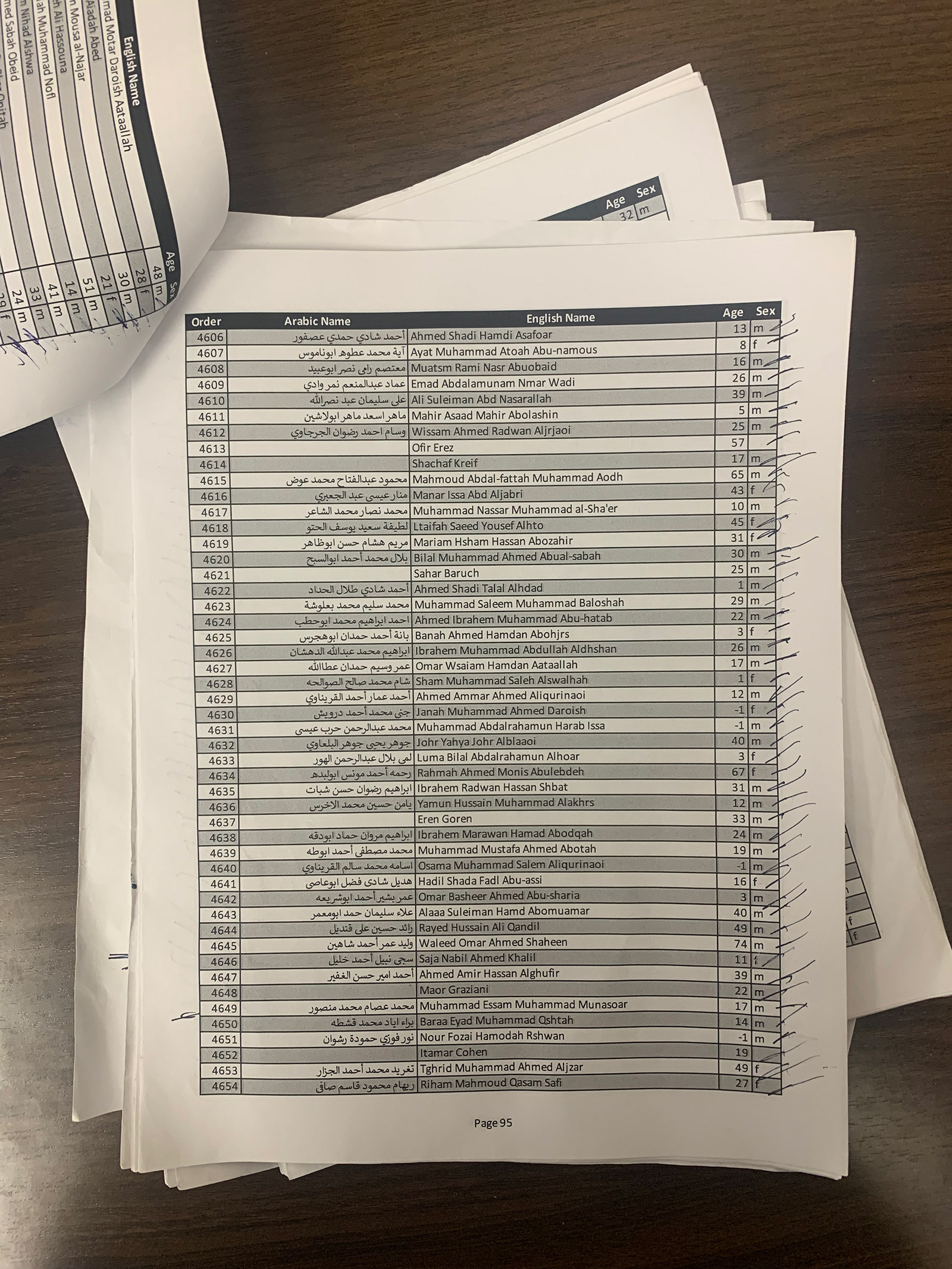

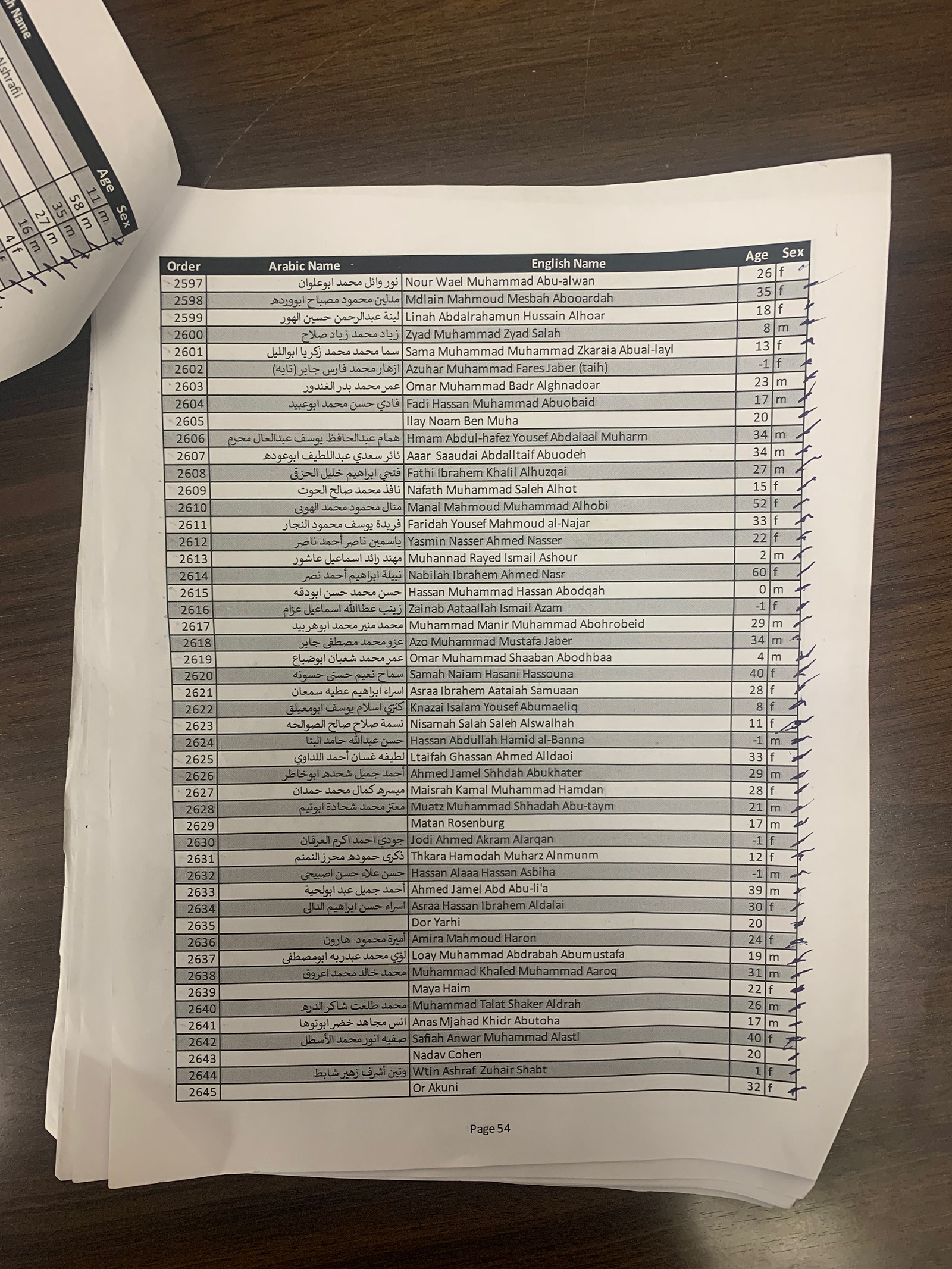

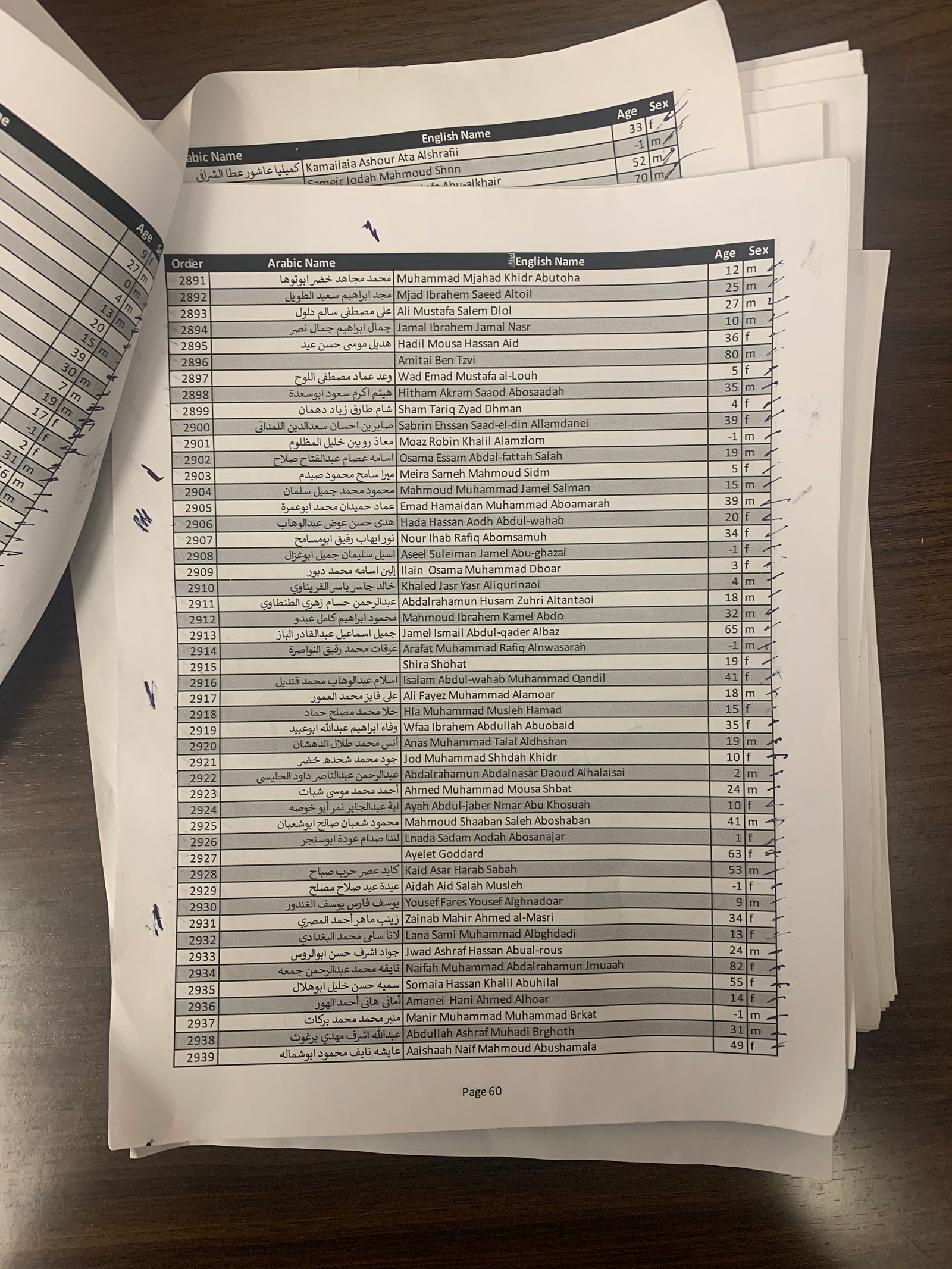

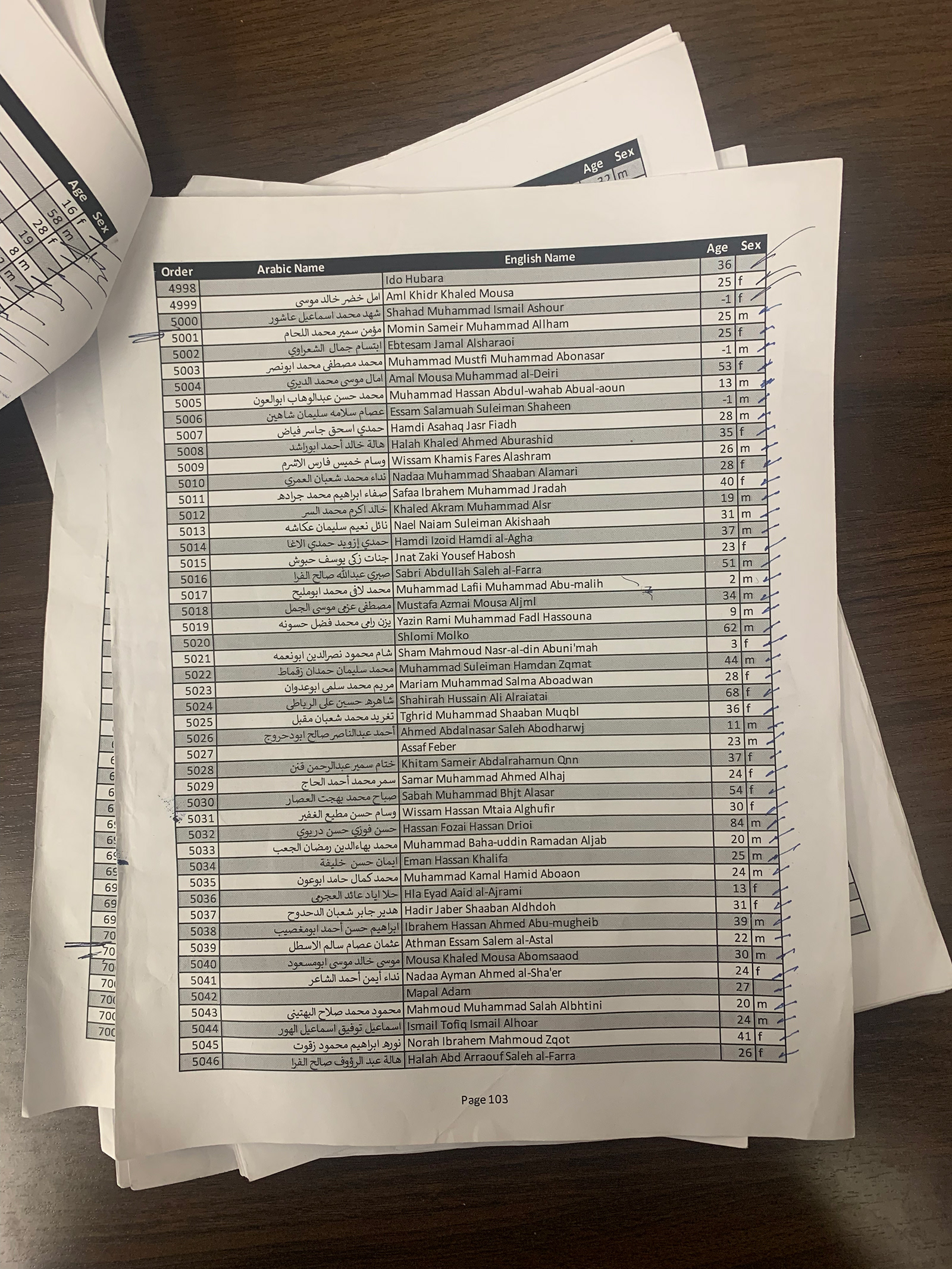

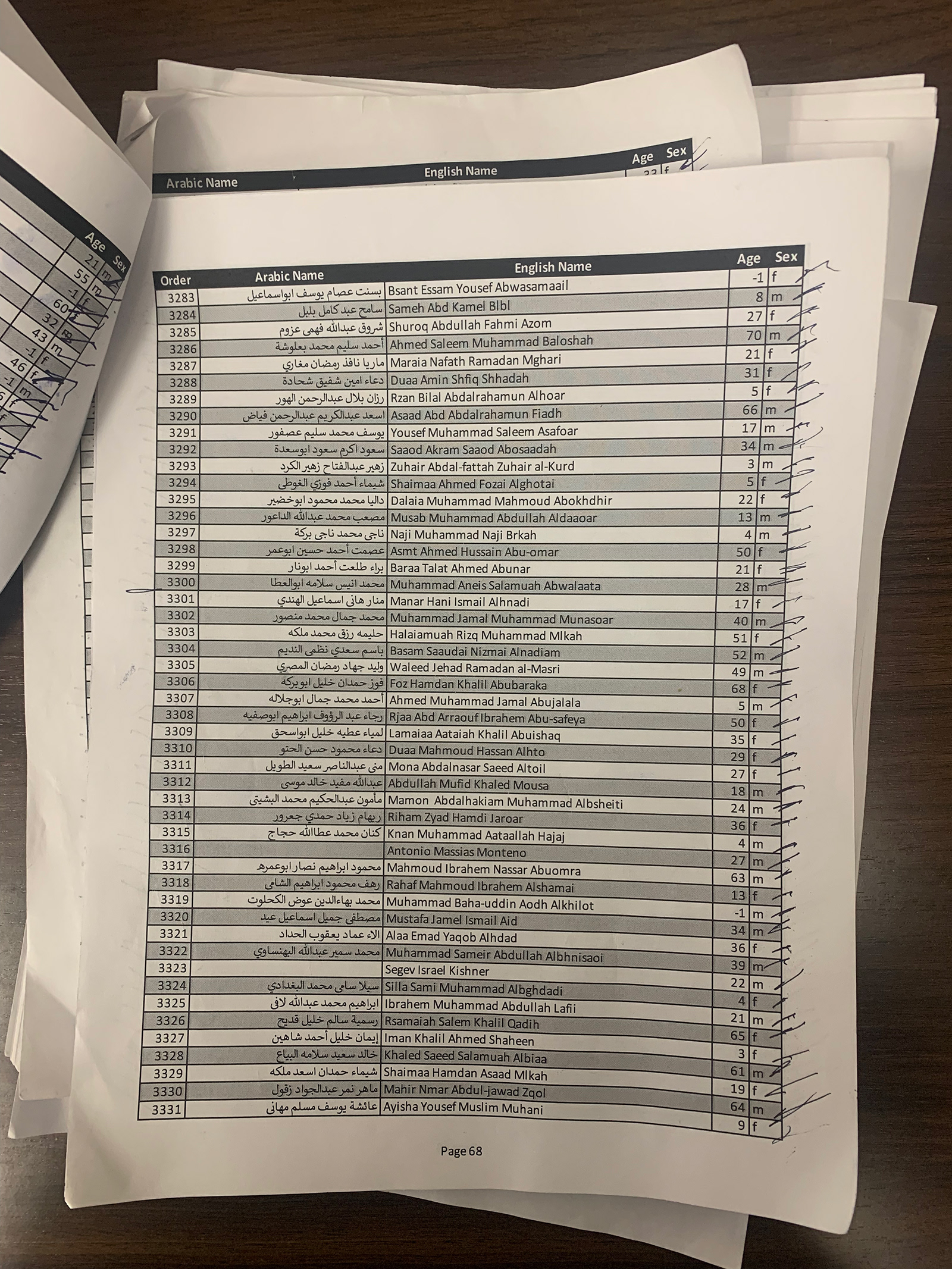

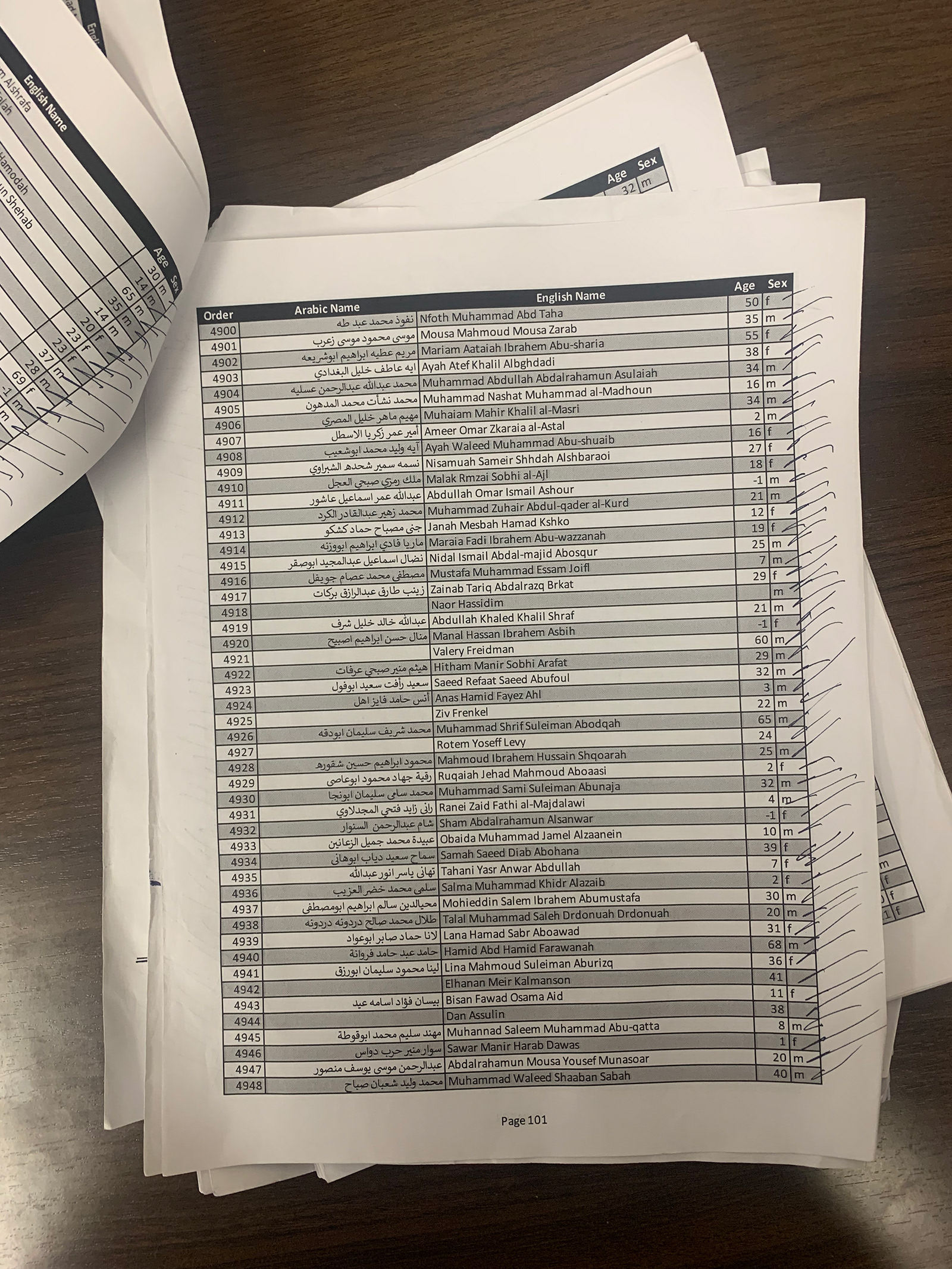

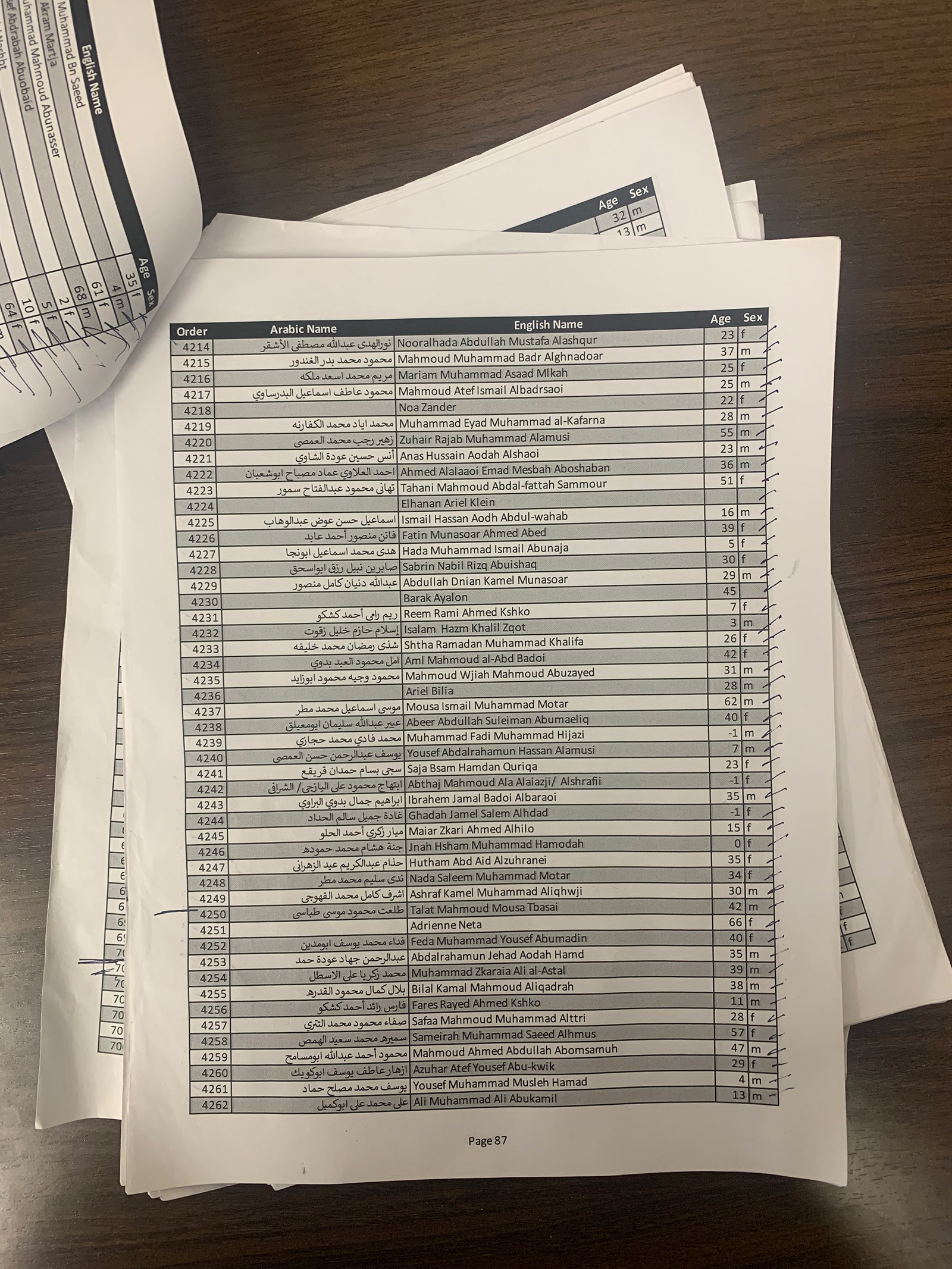

“We have read so far XXXX names of the people killed in Israel and in Gaza, in Gaza and in Israel since October 7th, 2023. We have attempted to gather all of their names, now more than 34,000. Publicly available records amount to around 16,000, fewer than half of those killed in Gaza alone, a number approximately equal to the number of children killed in Gaza. We invite you to read with us, to strike a drum, to pause in your day, to listen, to learn, to remember. These are the names….”

“These are the Names” grew out of an earlier project from the first six months of the war, in which a group of friends—Sasha Tycko and Jośe Londono, Peter and me and others—met each week to say aloud poems of grief and lament from traditions and cultures close to us (work from Palestinian and Syrian poets, Yiddish and Polish and German poets, and others), on the trust that poetry was a far more subtle instrument to express what we were going through than speeches and proclamations, including those with which we agreed.

As a moral intervention, we designed "These are the Names" to be simple in form and complex in content. It is part vigil, part guided meditation (adopting the liturgical form of the Yizkor service of Yom Kippur), and part political plea that the commons become a court, to which we submit our dossier of evidence for public consideration. We believe that the evidence, if you actually take the time to consider it syllable by syllable, argues for the elemental point that human compassion cannot be partitioned, and that to try to do so is to betray ourselves categorically.

Peter Habib, "These are the Names," Emory University quadrangle, Atlanta, GA / April 2024

The interior space of the project is mysterious and difficult. The names are exact identifiers of the dead and also empty of content, placeholders for strangers. It is a creative challenge to hold space in the mind and the heart for a stranger, and to sustain that stranger in a just opacity—not falsely converting that stranger into a familiar. It is likewise a creative challenge to ground one's ethics precisely in the incomprehensible—or more exactly, the incomprehensible-but-deeply-felt. It seems to me that such challenges are precisely the way tribal grievance transforms into collective grief, understanding as I do that collective mourning is one of the important ways civilizations mature.

In the month since we began “These are the Names,” Emory University has seen persistent student activism against the Israeli war in Gaza, and for the freedom of Palestine. The university has garnered international headlines for the police violence unleashed against non-violent protesters at the behest of the Emory president, Gregory Fenves, including the use of tear gas, rubber bullets, tasers, bodily assault, and arrest. We deplore the use of repression to silence dissent, which to us contravenes the very concept of a university. That said, “These are the Names” is not formally a part of student protest actions, and comparatively few student protesters have participated.

In this connection, the overwhelming response to this project has been no response, or no response that I can discern. Of those who do respond, mostly it has been positive. People have sometimes joined us—our friend José Londono has been present for many hours—for which we are grateful. Others have written to express their support.

We have received questions about the sources for the names, and details about who is and is not included. The data of those killed in Israel comes from formal Israeli channels (https://www.gov.il/en/pages/swords-of-iron-idf-casualties). These records include civilians and IDF soldiers, and also non-citizens of Israel killed on October 7th—migrant workers, various ex-pats, etc. The names of Palestinians come from “Tech for Palestine” (https://data.techforpalestine.org)—which seems to be the most accurate and complete document of all Palestinians killed since October 7th. This data is mostly collected from the Gaza Health Ministry and UN OCHA, and incorporates some publicly submitted names. Our list for “These are the Names” focuses specifically on Gaza, and does not include those killed in the West Bank since October 7th.

Our project has also met resistance. Peter is a Lebanese-American Christian and I am an American Jew, and we are overt in the presentation of difference, Peter wearing his keffiyeh and I my tallis. Most of the pushback has been directed to me as the Jewish face of the work. Some has come from what I would call the illiberal left (not the left I identify with). Mostly it has come from other Jews, Zionist or right-wing in their sympathies, who apparently view with fear and contempt anti- or non-Zionist Jews, or Jews who do not excuse, minimize, or evade the true depravity of Israel’s mass killing of Palestinian civilians. In this sense, “These are the Names” puts its finger on what Peter Beinart calls the “intra-Jewish ideological civil war” between Zionist and anti-Zionist American Jews, especially among younger people. Beinart believes this schism will define the American Jewish world for the next half century, and he may be right. I, who have spent much the last quarter century working on post-Holocaust memory cultures, see the split as between those Jews for whom “Never Again!” means “Never again to us,” and those for whom it means “Never again to anyone, including us.” I suppose it is obvious that I count myself in the latter group.

Jason Francisco and Peter Habib, "These are the Names," Emory University, Atlanta, GA / April 2024. Still from a video by Liran Razinsky.

Peter Habib, "These are the Names," Emory University, Atlanta, GA / April 2024

In the month that has passed since we began, after more than 40 hours, we have not yet reached the 10,000th name. It seems we are always still reaching the first.

Jason Francisco

Atlanta / May 7, 2024

Atlanta / May 7, 2024

This project owes everything to the wisdom and courage of Peter Habib, also his technical acumen in gathering names. The initial vision for the work was Peter's, and he first spoke about it in the initial weeks after October 7th. We are thankful for José Londono and other friends who have participated, including Beth Corrie, Liran Razinsky, Valérie Loichot, Sasha Tycko, Shreyas Sreenath, Jonathan Greenberg, and Craig Perry.