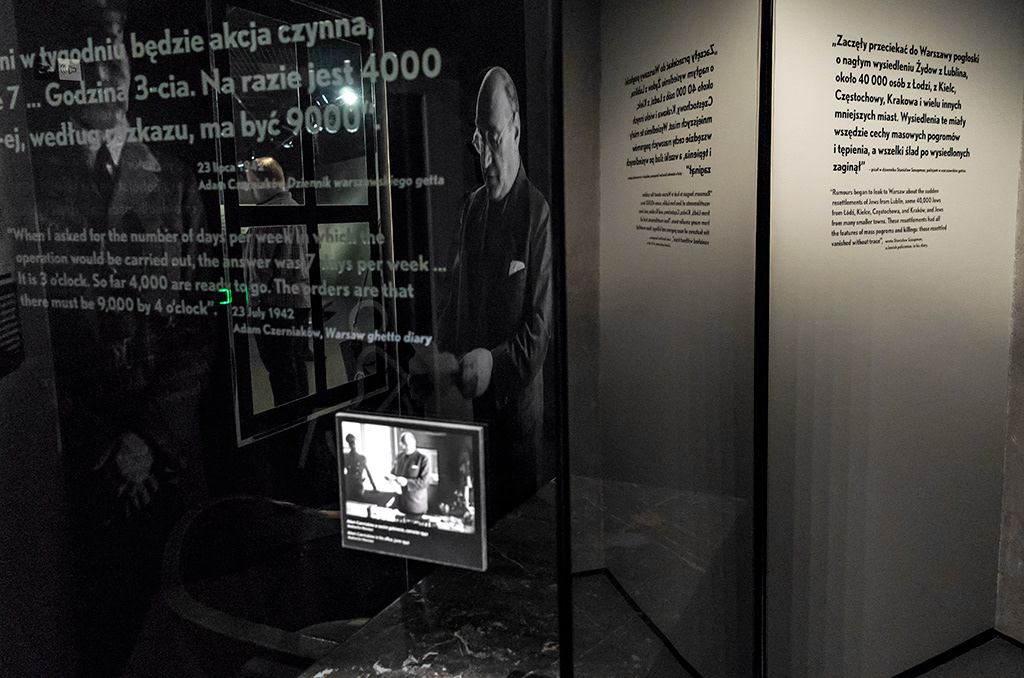

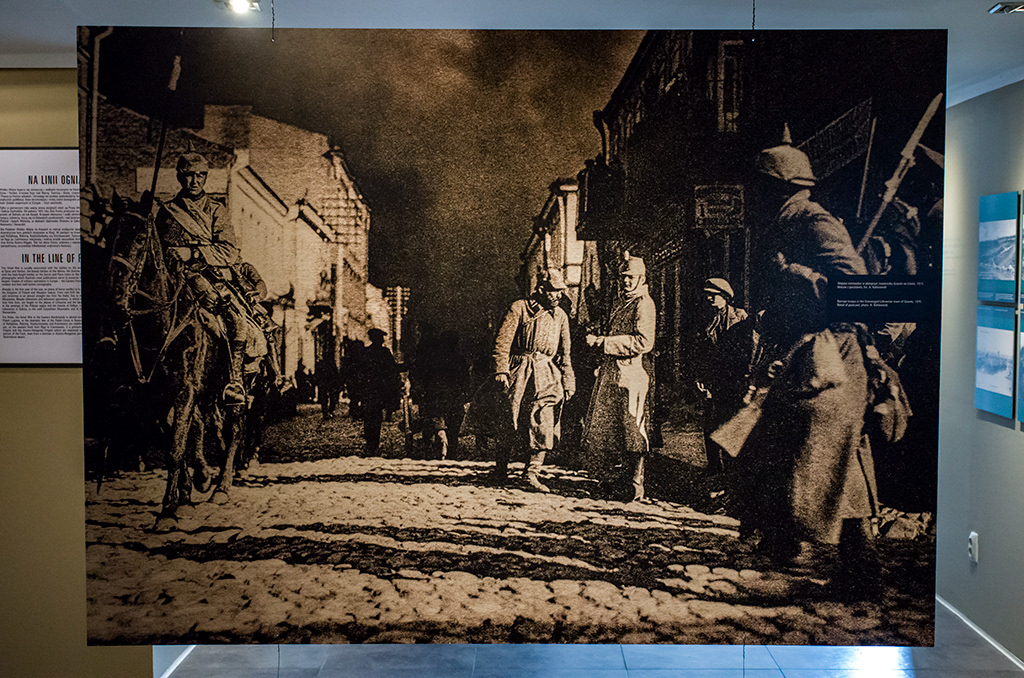

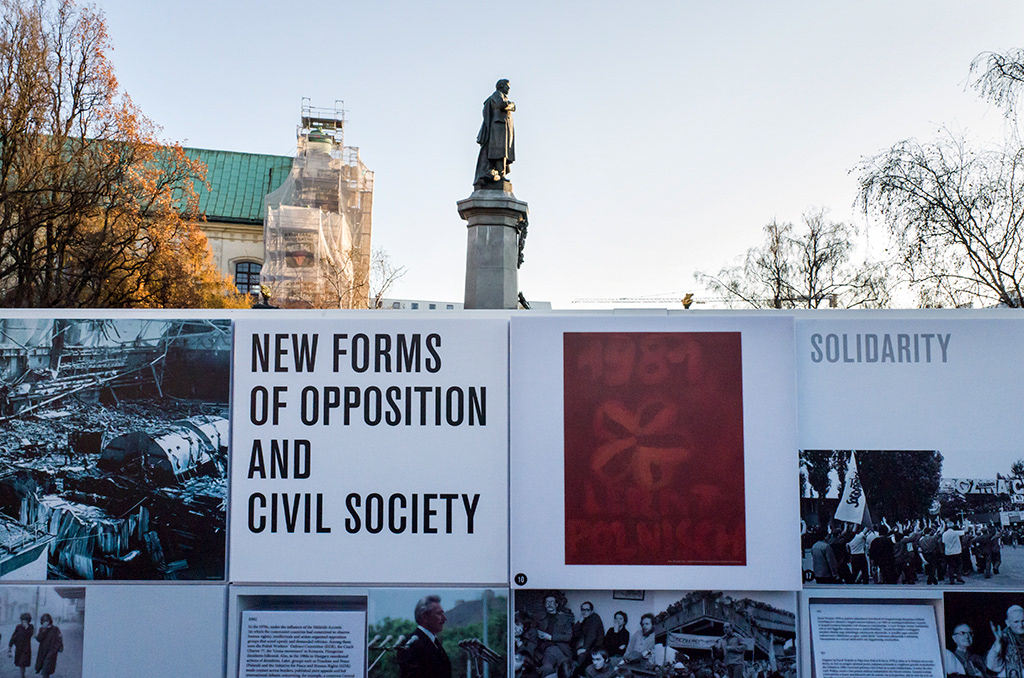

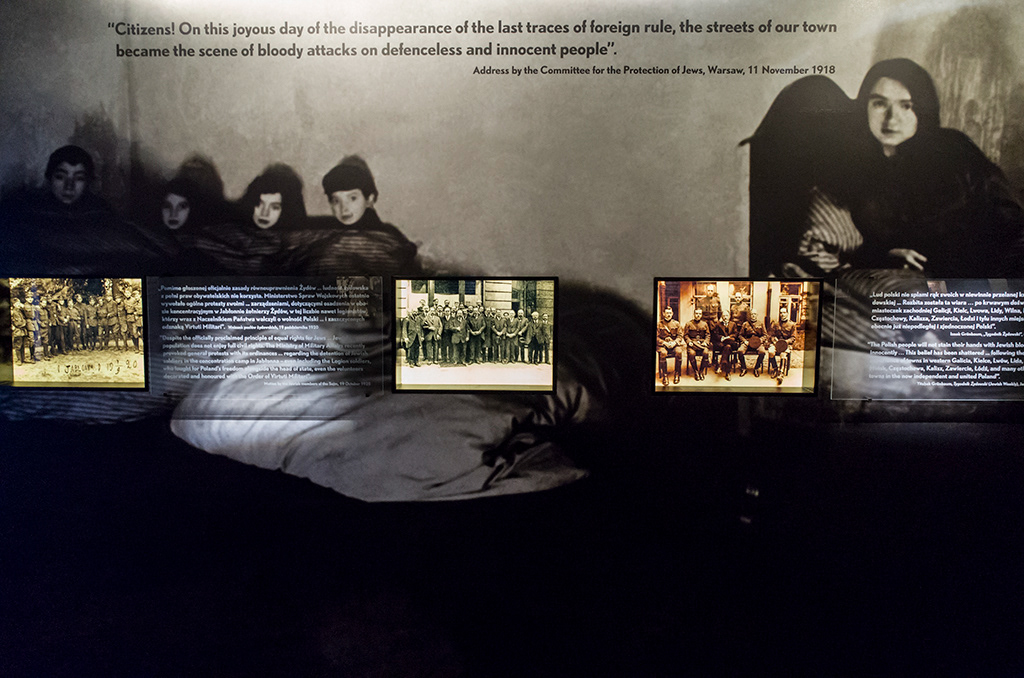

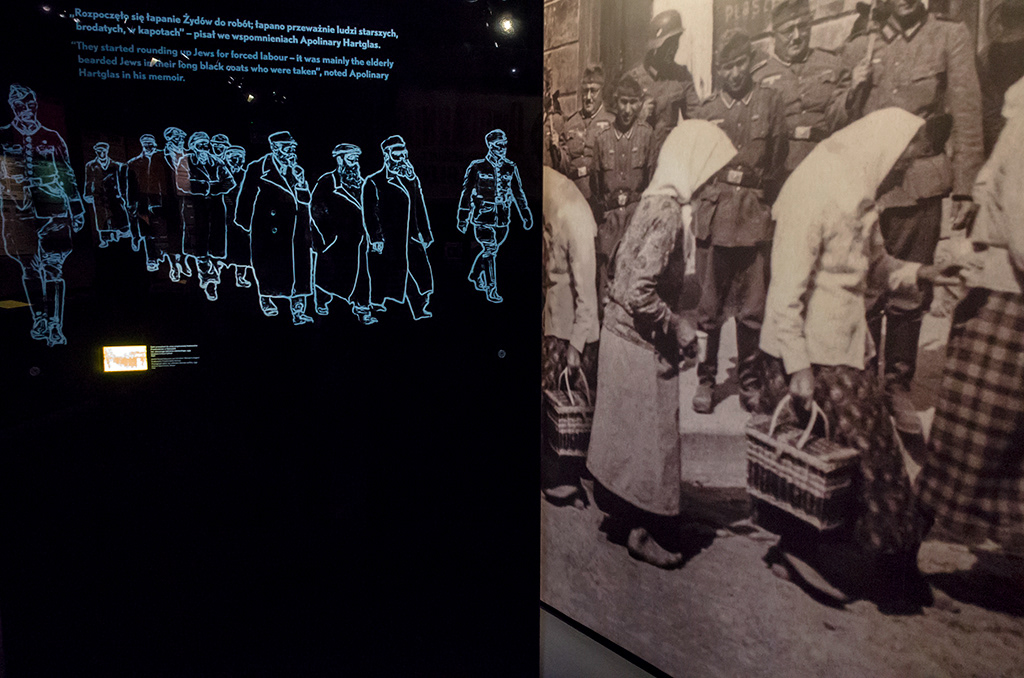

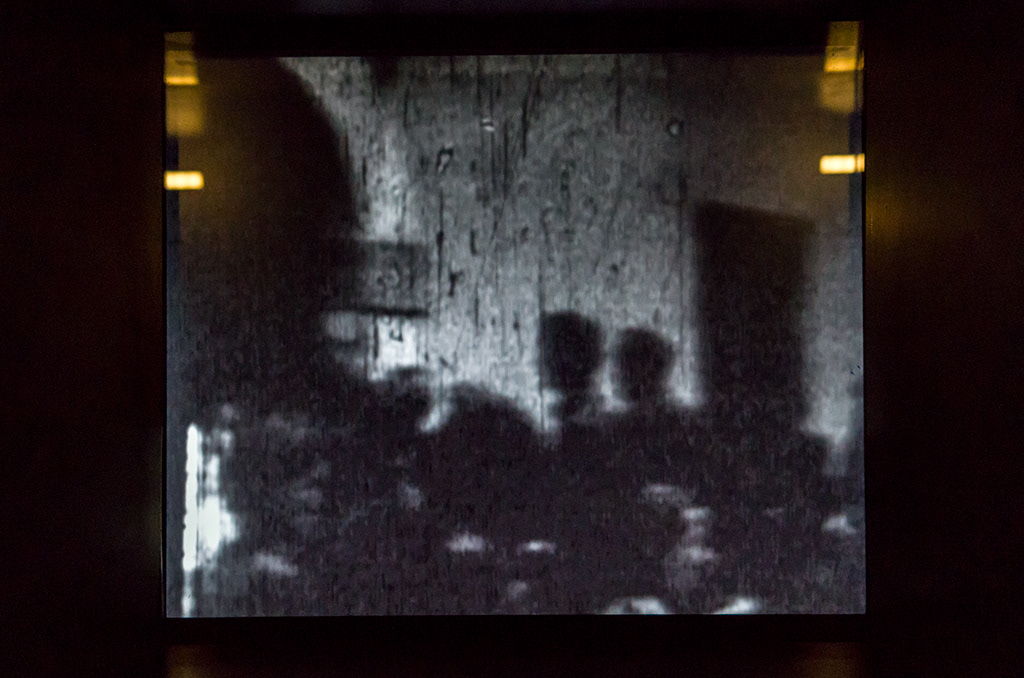

On Jerusalem avenue in Warsaw, there is a graffiti-tagged door that neither opens nor revolves to let you pass, an unmoving door stuck in a half-welcome, a door without the ordinary attributes of a door. Beyond it lies a shabby courtyard and the Fotoplastikon––the last Kaiserpanorama in Europe. It sits in a small square room––a startlingly large wooden cylinder, lit from within. an elderly couple is perched side by side on stools in front of it, peering through its brass-shaded lenses at rotating stereoscopic pictures of silent film stars and starlets of the 1920s. They whisper to one another and laugh quietly. these are the celebrities they don't quite remember, from the time of their parents' youth, when independent Poland was also young and the Fotoplastikon was already losing out as popular entertainment––to cinema, which is to say, moving images without the stillness of photography still embedded in it. I think to myself: if innocence is a wonder in children, how much moreso in the elderly, and innocent images––if any still exist––are a very pure delight. But when I gaze into the great cylinder's binocular show, I see something different. The rhythmic clicking-in and clicking-out of the antique faces snaps other pictures into my imagination. For me, the Fotoplastikon's darkness and its glow bring to my mind the images that the city otherwise adorns itself with, made of plaster and plastic, glass and bricks, and any substance that will carry a photograph. When I look into the Fotoplastikon, I see the city's picture-promises of the future, and I see its halls of memory, where the war that ruined everything abounds––rebounds––with new relevance. Like the door that is not a door, one picture changes places with another. Fate that is inert is also fate that is shaky with possibility. Whatever can be called the present in Warsaw seems to me inexplicably old and young, hard and vulnerable, hopeful and doubtful. I tell myself: the pictures I am not at liberty to ignore are precisely the ones the old man and the old woman come here not to look at.